TEACHING and LEARNING for REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

Taking Yourself Seriously is designed for anyone who wants to integrate “head, heart, hands, and human connections” in their research and writing. The intended audience is not limited to students. Nevertheless, a pedagogical current is obvious—the book's origins lie in Peter's research and writing courses; the Phases and Cycles and Epicycles frameworks are designed to be translated readily into assignments, classes, and stages of semester-long student projects; and theses or dissertations fit well under the category of a Synthesis of Theory and Practice. The pedagogical challenges of teaching students to take themselves seriously warrant, therefore, some more discussion.What follows takes the form of snapshots from Peter's journey teaching research and other courses for the Critical and Creative Thinking (CCT) Graduate Program at the University of Massachusetts Boston. CCT, despite the “thinking” in its name, is about changing and reflecting on practice. The Program aims to provide its mid-career or career-changing students with “knowledge, tools, experience, and support so they can become constructive, reflective agents of change in education, work, social movements, science, and creative arts” (CCT 2008). In this vein, it seems less important for us to describe the detail of the classroom mechanics and CCT course requirements, than to stimulate reflection and dialogue about the challenge of supporting students (and others) to develop as reflective practitioners.

A book cannot recreate for readers the experience of participating in classroom activities and the unfolding process of a program of studies. Even so, some readers might want us to explicate our line of thinking and relate it to what others have written and done. We do not, however, attempt that. Instead, we offer the snapshots in a spirit of opening up questions and pointing to a complexity of relevant considerations, not of pinning down answers with tight evidence. We encourage readers to participate in the online forum that accompanies this book (see Resources section later in Part 4) so as to engage the authors and each other in ongoing conversation and in sharing resources, struggles, and accomplishments.

* * *

1. Goals of research and engagement; goals of developing as a reflective practitioner

Each of the Phases of Research and Engagement is defined by a goal. I (Peter) made the phases and goals explicit after my first semester teaching research and writing to CCT's mid-career graduate students. One student, an experienced teacher, had dutifully submitted assignments, such as the Annotated Bibliography, all the time expressing skepticism that this course was teaching her anything new: “I have already taken research courses and know how to do research papers.” Indeed, I felt that most of her submissions did not help move her project forward; the form was there, but not the substance. I often asked her to revise and resubmit, emphasizing that the point was not to complete, say, the annotated bibliography just because I, the instructor, deemed this an essential part of a research project. The point was for her to do the annotated bibliography in a way that brought her closer to being able to say “I know what others have done before, either in the form of writing or action, that informs and connects with my project, and I know what others are doing now.” By the end of the semester I had made such goals and the corresponding Phases an explicit organizing structure for the course and other research projects. The resistance of this student had given me an invaluable push to rework my own syllabus.The goals of research and engagement represented, however, only half of what was going on in the research and writing course. I identified ten additional goals related to the process of pursuing a major research and writing project. Over the next year, helped by some teacher research (snapshot 2), I refined these Reflective Practitioner Goals. I have since incorporated both sets of goals into a Self-Assessment that students complete at the end of the research and writing course as well as at the end of their studies. (See also Assessment that Keeps the Attention Away from Grades in a way that is consistent with the two sets of goals, required Personal and Professional Development Workbook, and other expectations for Research Organization.)

2. Making space for taking initiative in and through relationships

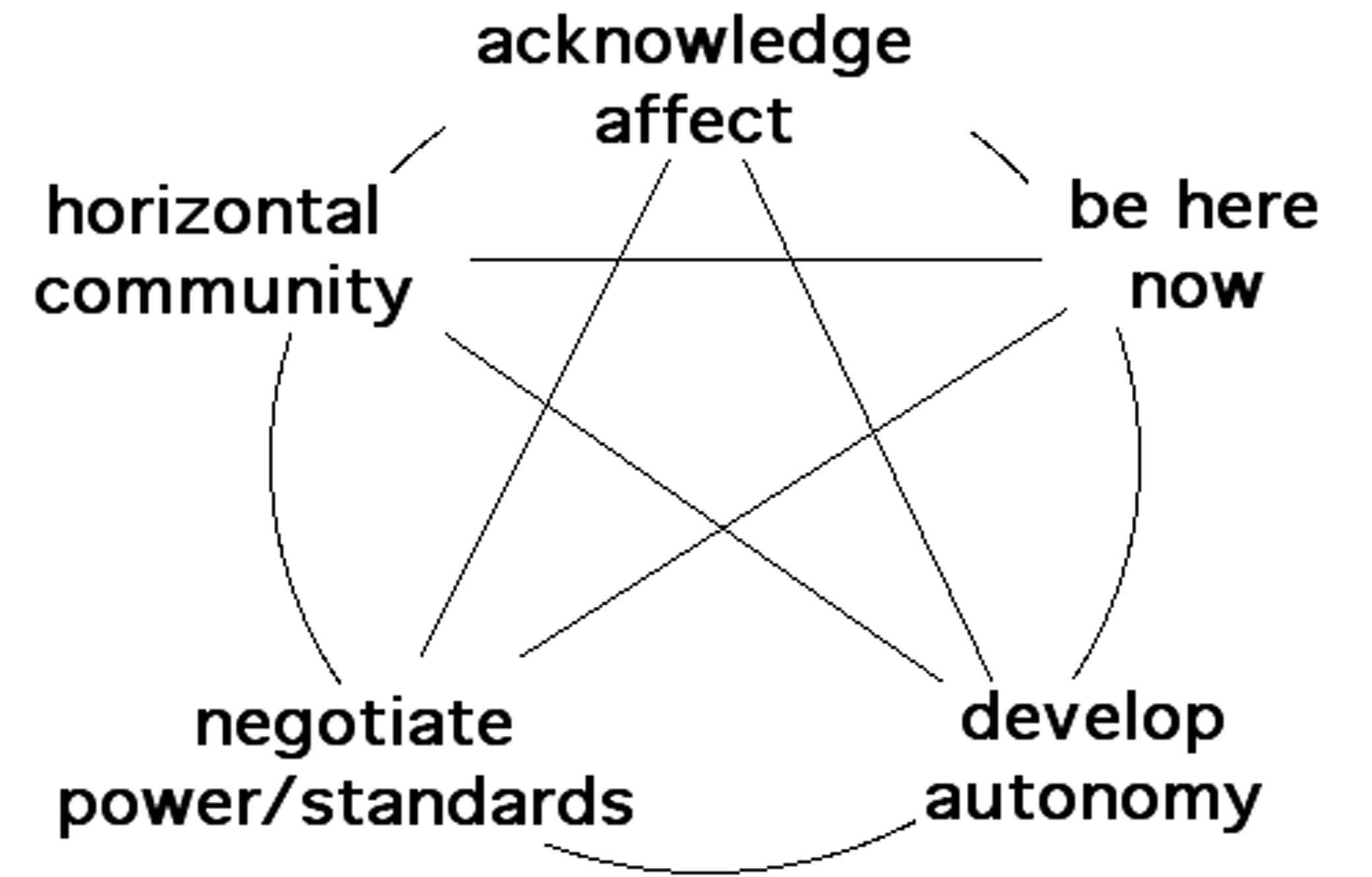

I want students to see Dialogue around Written Work as an important part of defining and refining research direction and questions. However, students are familiar with the system of submit a product, receive a grade, check that assignment off the to-do list, then move on to the next one. They know that they have to expose their submissions to the instructor, but are uncomfortable about subjecting their work to dialogue. My challenge, then, has been to get students into the swing of an unfamiliar system as quickly as possible so they can begin to experience its benefits.I chose to focus on this challenge when I participated in a faculty seminar on “Becoming a teacher-researcher” during my second year teaching CCT students (Taylor 1999). A month into semester the students in the research and writing course completed a survey about their expectations and concerns in working under what they called the “revise and resubmit” process. The participants in the faculty seminar then reviewed all the students' responses and brainstormed about qualities of an improved system and experience. We wrote suggestions on large Post-its, which we grouped and gave names to. Five categories or themes emerged: “negotiate power/standards,” “horizontal community,” “develop autonomy,” “acknowledge affect,” and “be here now.”

Five themes about improving the experience of dialogue around written work. (A sixth theme, "explore difference," was added later.)

In the following class I initiated discussion with the students around their responses and the themes generated by the faculty seminar. We clarified the meaning of the themes and explored the tensions between them (conveyed by the connecting lines in the figure above). For example, “develop autonomy” stood for digesting comments and making something for oneself—neither treating comments as dictates nor insulating oneself by keeping from the eyes of others. Yet, “negotiate power/standards” recognized that students made assumptions about my ultimate power over grades, which translated into their thinking that I expected them to take up my suggestions. These assumptions about the “vertical” relationship between instructor and student do have to be aired and addressed, but “horizontal community” captured the need for students to put effort into building other kinds of relationship.

During the rest of the semester, class discussions continued to refer to the themes and tensions. We applied them to the whole research and engagement process, not only to dialogue around written work. I looked for a substitute for “autonomy” after some students construed this word as going their own way and not responding to comments of others, including their instructors. When “taking initiative” was suggested by my wife, I realized that it applied to all five themes. I emailed my students: “[The challenge is to] take initiative in building horizontal relationships, in negotiating power/standards, in acknowledging that affect is involved in what you're doing and not doing (and in how others respond to that), in clearing away distractions from other sources (present and past) so you can be here now.” Don't wait for the instructor to tell you how to solve an expository problem, what must be read and covered in a literature review, or what was meant by some comment you don't understand. Don't put off giving your writing to the instructor or to other readers and avoid talking to them because you're worried that they don't see things the same way as you do.

A longer phrase soon emerged: “Taking initiative in and through relationships.” That is, don't expect to learn or change on one's own. Build relationships with others; interact with them. This doesn't mean bowing down to their views, but take them in and work them into your own reflective inquiry until you can convey more powerfully to them what you are about (which may or may not have changed as a result of the reflective inquiry). Finally, do not expect learning or change to happen without jostling among the five themes-in-tension. The themes do not always pull you in the same direction, so your focus might move from one to another, rather than trying to attend to all of them simultaneously.

Of course, laying out this “mandala” did not specify how to teach and support students to take progressively more initiative. Nevertheless, I believe that talking about the five points helped the students recognize themselves and take more initiative in their learning relationships. Since then I have presented the insights from the original group to new cohorts—often adding “explore difference” as a sixth theme.

(Presenting an analysis or action plan developed by a previous group is never as powerful as a group creating its own. Given this, I have asked each new cohort in the research and writing course to contribute to ongoing teacher research around the question: “By what means can the group function as a support and coaching structure to get most students to finish their reports by the end of the semester?”; see Support and Coaching Structure).

3. Opening wide and focusing in

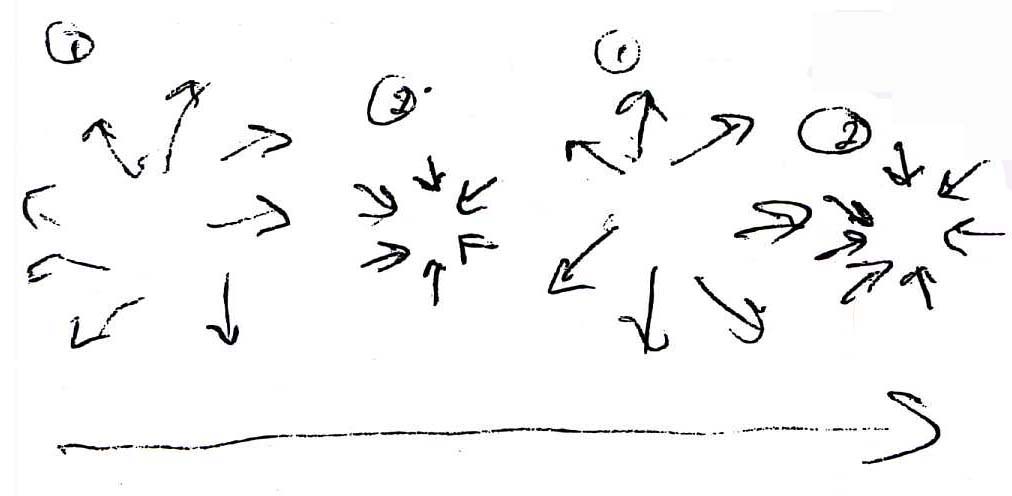

A colleague in the faculty seminar on teacher research (snapshot 2) participated in the first class of the research and writing course as if he were a student. The class consisted of: an overview of the phases from me; a Q&A session with a student from the previous year's class (during which I was absent from the room); and some freewriting, rough drafting, and peer sharing of an initial project description. The colleague, Emmett Schaeffer, commented afterwards on the oscillation the students faced between opening wide and focusing in. He also noted that the students were somewhat “dazed” about how much was opened up and put in play during this first session (Box 1). As my thank you email expressed (Box 2), having someone else see what was going on helped me articulate and own a tension that runs through most of my teaching.Box 1. Comments from a colleague on the student experience at the start of the research and writing course

| → on “divergent” thinking certainly, at first, and, if I understand correctly, throughout the process, you think one engaged in research and engagement should remain open, both to others and their opinions, but also to one's “divergent” (from one's conscious, explicitly formulated path) thinking, feeling, etc. --sort of [1] opening wide, [2] focusing and formulating,  [1] the “opening wide” could take the form of:

free writing sharing (with a partner, teacher, group) one's formulations (written or oral)

My guess as to purpose: (of course partly you don't choose this outcome, it's rather a function of students' previous training but to some extent I think it's inherent in your approach and philosophy)

(and reflecting on the doing that requires some doing). 2. everything up in the air (not settled, in place, foreclosed, etc.) to maximize

b. their agency in influencing settling c. model of anxiety and confusion inherent (at first) in sharing and remaining open, while proceeding to try various ways to “sort things out” |

Box 2. Thank you email about the affirmation-articulation connection

| Emmett, I really appreciate your keen observations and the work you did in synthesizing them into the notes. What we did together was rare and special -- I could only remember one other time I got a colleague's observations that affirmed but also helped me articulate and own what I was doing. That time was an ESL and Spanish teacher who had asked to visit a class of mine about biology and society. She noted my comfortable use of ambiguity. Much followed for me from her naming this. In fact, I suspect that the affirmation-articulation connection is a key to the observed person doing something productive with the observations. Thanks, Peter |

4. From educational evaluation to constituency building

The same observation about having to move between opening out and focusing in was made independently a few years later by a student, herself an experienced college teacher, when she summarized the experience of the course on evaluation and action research. Snapshots 1 to 3 have not mentioned that course, but it was evolving at the same time as the course on research and writing. When I first took over teaching this second course, the title and emphasis was educational evaluation. I soon had this changed to evaluation of educational change so as to clarify that it was not about assessment of students. Moreover, to meet the needs of the diverse, mid-career professionals and creative artists that enter CCT, “educational change” had to be construed broadly to include organizational change, training, and personal development, as well as curricular and school change.The revised title still missed the central motivation for the course in the CCT curriculum, which was: “If you have good ideas, how do you get others to adopt or adapt them?” Put in other words: “How do you build a constituency around your idea?” This concern can lead researchers into evaluating how good the ideas actually are (with respect to some defined objectives) so they can demonstrate this to others. It can also lead a researcher to work with others to develop the idea so it becomes theirs as well and thus something they are invested in.

Taking an individual who wants “to do something to change the current situation, that is, to take action” as the starting point, Action Research became the central thread. The course title was eventually changed again to reflect the emphasis on Action Research for Educational, Professional and Personal Change. The “Cycles and Epicycles” model that emerged made room for group facilitation, participatory planning, and reflective practice, as well as for systematic evaluation. The next two snapshots touch on group processes; the one after links the research side of Action Research to Problem-Based Learning.

5. Conditions for a successful workshop

My own research during the 1980s and 1990s focused on the complexity of ecological or environmental situations and of the social situations in which the environmental research is undertaken. Since the 1990s collaboration has become a dominant concern in environmental planning and management, although the need to organize collaborative environmental research can be traced back at least into the 1960s (Taylor et al. 2008). Collaboration is self-consciously organized through the frequent use of workshops and other “organized multi-person collaborative processes” (OMPCPs).I started to try to make more sense of the workshop form after participating during the first half of 2000 in four innovative, interdisciplinary workshops primarily in the environmental arena (Taylor 2001). Two ideals against which I assessed these workshops were that group processes can: a) result in collaborators’ investment in the product of the processes; and b) ensure that knowledge generated is greater than any single collaborator or sum of collaborators came in with (see discussion in Part 4 of strategic participatory planning). As a postscript to my analysis of why a workshop (or OMPCP) might be needed to address the complexity of environmental issues, I assembled a list of guidelines or heuristics about making workshops in general work.

At my first presentation on this topic there was in the audience a professional facilitator, Tom Flanagan, who offered to help me develop a more systematic set of principles for bringing about successful workshops. The process he led me through involved:

Box 3. Criteria and Conditions for a Successful Workshop

| A. Two criteria of success i) the outcome is larger and more durable than what any one participant came in with. Durable means B. Conditions that might contribute directly or indirectly to these criteria being fulfilled |

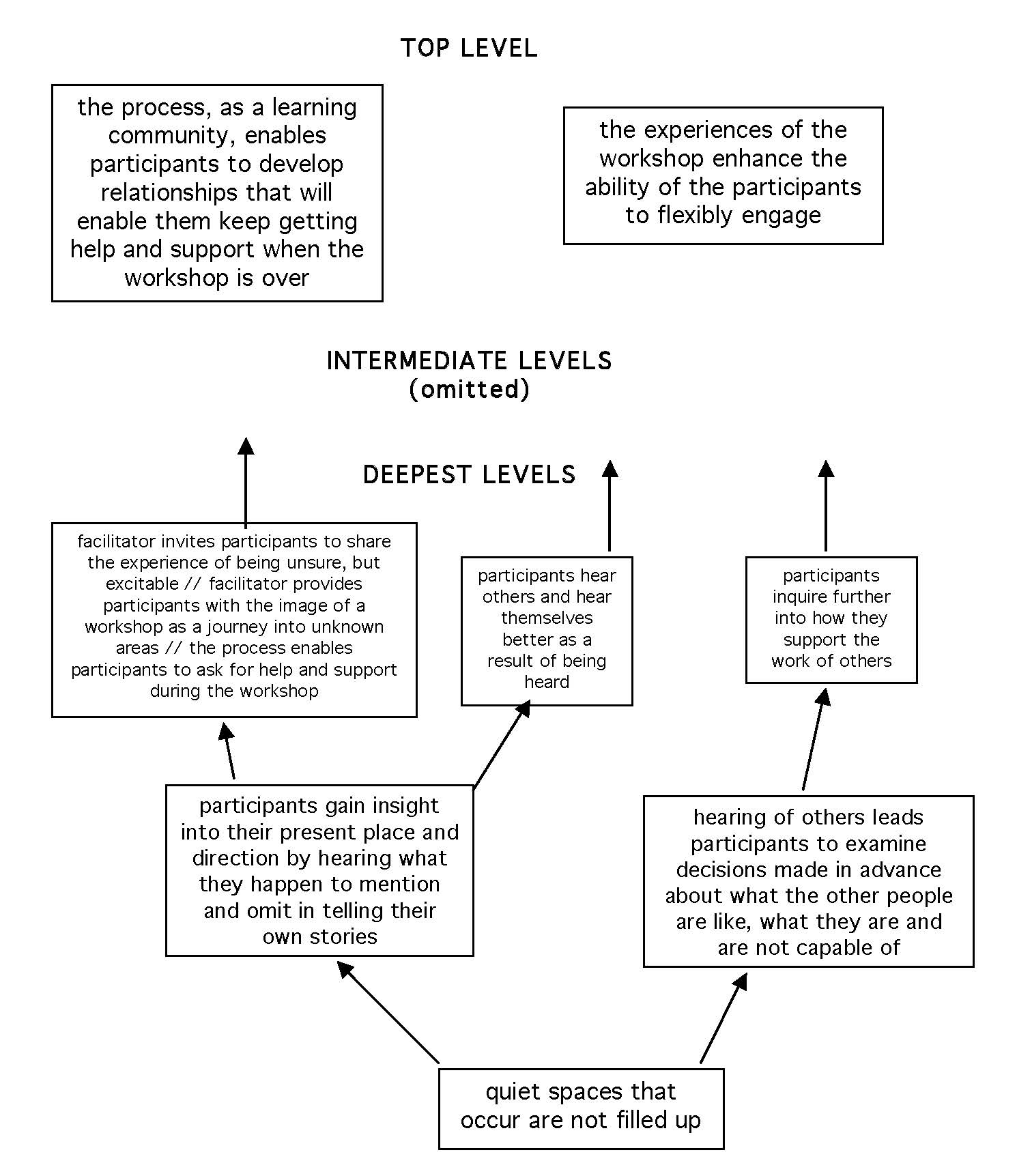

Tom's intention was only to introduce me to structural modeling, not to lead me systematically through the full process, so I should not over-interpret the outcome of our computer-aided analysis. I include here only the deepest three layers and the top of the model to help readers picture a structural model (see figure below). Let me draw attention, however, to the deepest condition, “quiet spaces that occur are not filled up.” It is no small challenge for someone organizing or facilitating a workshop (or OMPCP) to ensure that this condition is met. Conversely, when we try to squeeze too much in a limited time and the quiet spaces condition is not met, we should not be surprised that the criteria for a successful workshop are not achieved.

Extracts from the structural model

6. Four R's of developing as a collaborator

Group processes not only need skillful and effective facilitators; they also need participants or collaborators who are skilled and effective in contributing to the desired outcomes. To develop skills and dispositions of collaboration requires researchers (and researchers-in-training) to make opportunities for practicing what they have been introduced to and to persist even when they encounter resistance. What moves them to pursue such development?I have had an opportunity since 2004 to address this issue through an annual series of experimental, interaction-intensive, interdisciplinary workshops “to foster collaboration among those who teach, study, and engage with the public about scientific developments and social change.” The workshops are documented in detail on their websites (NewSSC 2008), but a thumbnail sketch would be: They are small, with international, interdisciplinary participants of mixed rank (i.e., from graduate students to professors). There is no delivery of papers. Instead participants lead each other in activities, designed before or developed during the workshops, that can be adapted to college classrooms and other contexts. They also participate in group processes that are regular features of the workshops and are offered as models or tools to be adapted or adopted in other contexts. The themes vary from year to year, but each workshop lasts four days and moves through four broad, overlapping phases: exposing diverse points of potential interaction; focusing on detailed case study; activities to engage participants in each others' projects; and taking stock. The informal and guided opportunities to reflect on hopes and experiences during the workshop produce feedback that shapes the unfolding program as well as changes in the design of subsequent workshops.

The ongoing evolution of the workshops has been stimulated not only by written and spoken evaluations, but also by an extended debriefing immediately following each workshop and by advisory group discussions, such as one in 2008 that addressed the question of what moves people develop themselves as collaborators. A conjecture emerged that this development happens when participants see an experience or training as transformative. After reviewing the evaluations we identified four “R's”—respect, risk, revelation, and re-engagement—as conditions that make interactions among participants transformative (Box 4; see Taylor et al. 2011 for elaboration and supporting quotations from the evaluations). A larger set of R's for personal and professional development will be presented in snapshot 9 (indeed, the larger set pre-dated and influenced the formulation of these 4R's).

Box 4. Four R's that make interactions among researchers transformative

| 1. Respect. The small number and mixed composition of the workshop participants means that participants have repeated exchanges with those who differ from them. Many group processes promote listening to others and provide the experience of being listened to. Participation in the activities emphasizes that each participant, regardless of background or previous experience has something valuable to contribute to the process and outcomes. In these and other ways, respect is not simply stated as a ground rule, but is enacted. 2. Risk. Respect creates a space with enough safety for participants to take risks of various kinds, such as, speaking personally during the autobiograph-ical introductions, taking an interest in points of view distant in terms of discipline and experience, participating—sometimes quite playfully—during unfamiliar processes, and staying with the process as the workshop unfolds or “self-organizes” without an explicit agreement on where it is headed and without certainty about how to achieve desired outcomes. 3. Revelation. A space is created by respect and risk in which participants bring to the surface thoughts and feelings that articulate, clarify and complicate their ideas, relationships, and aspirations—in short, their identities. In the words of one participant: “The various activities do not simply build connections with others, but they necessitate the discovery of the identity of others through their own self-articulations. But since those articulations follow their own path, one sees them not as simple reports of some static truth but as new explorations of self, in each case. Then one discovers this has happened to oneself as much as to others-one discovers oneself anew in the surprising revelations that emerge in the process of self-revelation.” 4. Re-engagement. Respect, risk, and revelation combine so that participants' “gears” engage. This allows them to sustain quite a high level of energy during throughout the workshop and engage actively with others. Equally important, participants are reminded of their aspirations to work in supportive communities—thus, the prefix re-engage. Participants say they discover new possibilities for working with others on ideas related to the workshop topic. |

7. Problem-based learning

In contrast to the step-by-step progression in most accounts of action research, the “cycles and epicycles” model allows for extensive reflection and dialogue. This is essential not only for constituency-building, but also for problem-finding, that is, for ongoing rethinking of the nature of the situation and the actions appropriate to improving it. In this sense action research mirrors Problem-Based Learning (PBL), at least the kind of PBL that begins from a scenario in which the problems are not well defined (Greenwald 2000). Stimulated by the work of my CCT colleague, Nina Greenwald, I began to introduce a PBL approach in the evaluation course which led it evolve into an Action Research course. I then brought PBL into other courses on science in its social context. The way I have come to teach with PBL is given in Box 5 (extracted from Taylor 2008a, which includes links to examples of PBL scenarios and student work).Box 5. Problem-Based Learning, an Overview

| Students brainstorm so as to identify a range of problems related to an instructor-supplied scenario then choose which of these they want to investigate and report back on. The problem definitions may evolve as students investigate and exchange findings with peers. If the scenario is written well, most of the problems defined and investigated by the students will relate to the subject being taught, but instructors have to accept some “curve balls” in return for Interdisciplinary Coaching: The instructors facilitate the brainstorming and student-to-student exchange and support, coach the students in their individual tasks, and serve as resource persons by providing contacts and reading suggestions drawn from their longstanding interdisciplinary work and experience. Inverted pedagogy: The experience of PBL is expected to motivate students to identify and pursue the disciplinary learning and disciplined inquiry they need to achieve the competencies and impact they desire. (This inverts the conventional curriculum in which command of fundamentals is a prerequisite for application of our learning to real cases.) KAQF framework for inquiry and exchange: This asks students to organize their thinking and research with an eye on what someone might do, propose, or plan on the basis of the results, presumably actions that address the objective stated in the PBL scenario. Internet facilitation: The internet makes it easier to explore strands of inquiry beyond any well-packaged sequence of canonical readings, to make rapid connections with experts and other informants, and to develop evolving archives of materials and resources that can be built on by future classes and others. |

PBL was enthusiastically pursued by one CCT student and led to her transformation from community-college librarian with no science background to participant in campaigns around health disparities and employment as a research assistant in the biomedical area. Although I will not tell her story here, it moves me to recount some earlier reflections on students' development in the CCT Program as a whole, which make up the last two snapshots.

8. Journeying

One course I taught for the first time after I joined the CCT Program was “Critical Thinking.” Mid-way through the first semester, when the topic was revising lesson plans, we revisited a demonstration I had made during the first class. The details are not important here, except to say that some students had interpreted the demonstration as a science lesson even though the science aspect seemed unimportant to me. Discussion of the discrepancy led me to articulate my primary goal more clearly, which was that students would puzzle over the general conundrum of how questions that retrospectively seem obvious ever occur to us. That puzzle was meant to lead into considering how we might be susceptible to further re-seeings. The image that arose for me during the discussion was that a person's development as a critical thinker is like undertaking a personal journey into unfamiliar or unknown areas. Both involve risk, open up questions, create more experiences than can be integrated at first sight, require support, yield personal change, and so on. This journeying metaphor differs markedly from the conventional philosophical view of critical thinking as scrutinizing the reasoning, assumptions, and evidence behind claims (Ennis 1987, Critical Thinking Across The Curriculum Project 1996). Instead of the usual connotations of “critical” with judgement and finding fault according to some standards (Williams 1983, 84ff), journeying draws attention to the inter- and intra-personal dimensions of people developing their thinking and practice.The image of critical thinking as journeying gave me a hook to make sense of my development as a teacher. In narrating my own journey, I attempted to expose my own conceptual and practical struggles in learning how to decenter pedagogy without denying the role I had in providing space and support for students’ development as critical thinkers (Taylor 2008b, but written circa 2000). The central challenge I identified was that of helping people make knowledge and practice from insights and experience that they are not prepared, at first, to acknowledge—something that seems relevant to teaching research and engagement as well as critical thinking. Several related challenges for the teacher or facilitator emerged, which are summarized in Box 6.

Box 6. Helping people make knowledge and practice from insights and experience that they are not prepared, at first, to acknowledge

| Teacher-facilitators should: a) Help students to generate questions about issues they were not aware they faced. b) Acknowledge and mobilize the diversity inherent in any group, including the diversity of mental, emotional, situational, and relational factors that people identify as making re-seeing possible. c) Help students clear mental space so that thoughts about an issue in question can emerge that had been below the surface of their attention. d) Teach students to listen well. (Listening well seemed to help students tease out alternative views. Without alternatives in mind scrutiny of one's own evidence, assumptions and logic, or of those of others is difficult to motivate or carry out; see also point i, below. Being listened to, in turn, seems to help students access their intelligence—to bring to the surface, reevaluate, and articulate things they already know in some sense.) e) Support students on their journeys into unfamiliar or unknown areas (see paragraph above). f) Encourage students to take initiative in and through relationships (see snapshots 2 and 3 above). g) Address fear felt by students and by oneself as their teacher. h) Have confidence and patience that students will become more invested in the process and the outcomes when insights emerge from themselves. i) Raise alternatives. (Critical thinking depends on inquiry being informed by a strong sense of how things could be otherwise. People understand things better when they have placed established facts, theories, and practices in tension with alternatives.) j) Introduce and motivate “opening up themes,” that is, propositions that are simple to convey, but always point to the greater complexity of particular cases and to further work needed to study those cases (Taylor 2005). k) Be patient and persistent about students taking up the alternatives, themes, and other tools and applying them to open up questions in new areas. (Experiment and experience are needed for students—and for teachers—to build up a set of tools that work for them.) l) Take seriously the creativity and capacity-building that seems to follow from well-facilitated participation (see snapshots 5 and 6), while still allowing space for researchers to insert the “trans-local,” that is, their analysis of changes that arise beyond the local region and span a larger scale than the local. |

9. Many R's

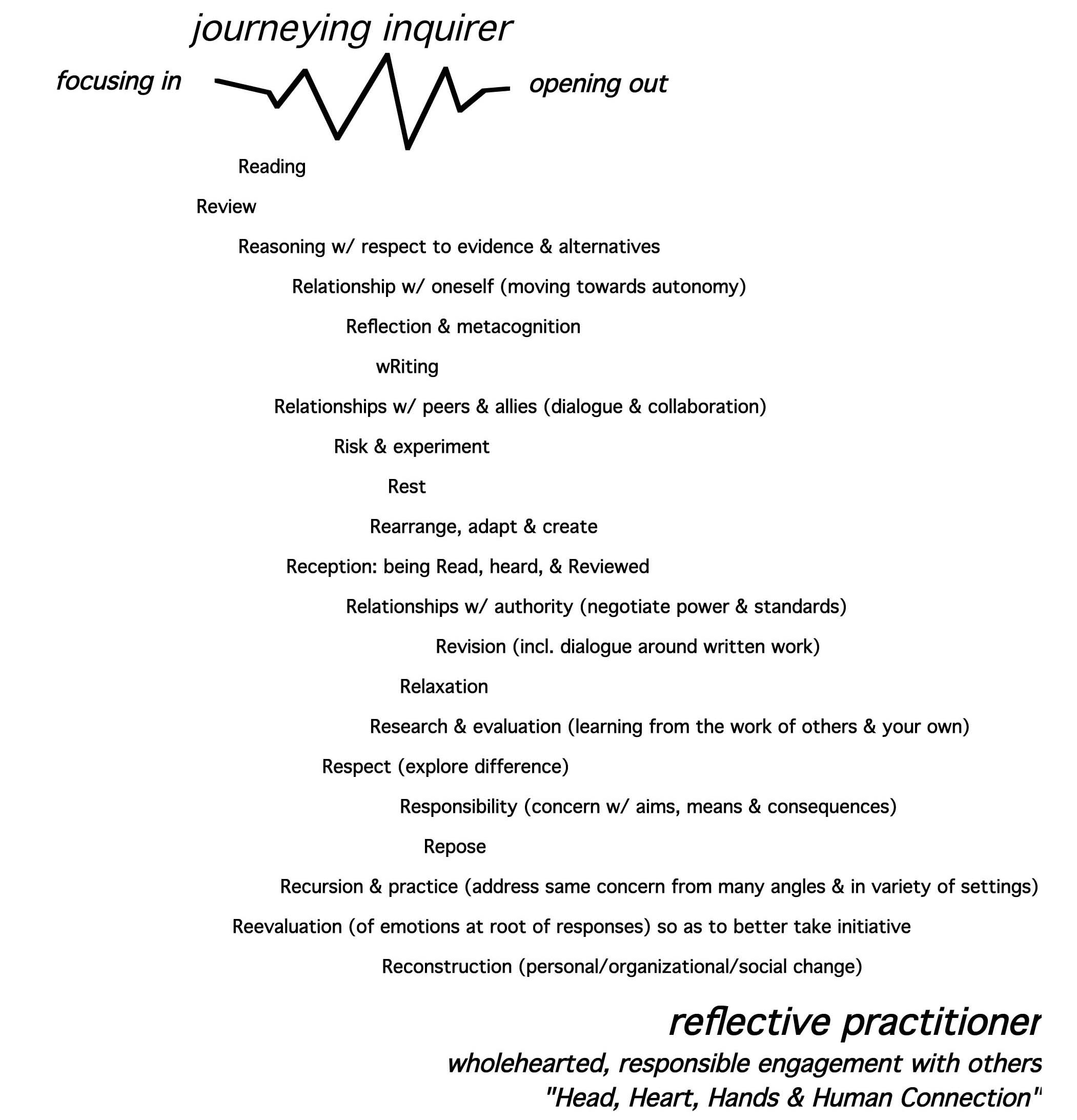

When the CCT graduate program was moved under a Department of Curriculum and Instruction, I decided to learn more about the theory that guided that field. I came across Doll's (1993) account of postmodern curriculum design, which centers on his “4R's”: richness, recursion, relation, and rigor. My immediate response was that Doll's R's do not capture a lot of what goes into CCT students' mid-career personal and professional development. I soon had twelve R's, and then more. The figure below took shape as I played with ways to convey that some R's will make limited sense until more basic Rs have been internalised and that opening-out periods alternate with periods of consolidating experiences to date.

The Rs of personal and professional development

I sometimes present this schema to students as a way to take stock of their own development. I suggest that they reflect at the end of each semester. For as many Rs as make sense, they should give an example and articulate their current sense of the meaning of any given R. I also use the many R's to remind myself as a teacher to expect the flow of any student's development to be windy and less than direct. (In this sense the schema of many R's stands as a counterpoint to the popular idea of backward design in curriculum, that is: identify desired results; determine acceptable evidence of students achieving those results; plan learning experiences and instruction accordingly, making explicit the sought-after results and evidence; Wiggins and McTighe 2005.)

* * *

The snapshots from Peter's journey suggest a windy and less-than-direct flow of development as a teacher and facilitator of research and engagement. Although we can imagine readers thinking they need to see more of the action and background behind the snapshots, we will not try to fill in more. Instead, we end with the hope that the account of this pedagogical journey, together with the tools and frameworks of Parts 1 and 2 as well as the illustrations in Part 3, help you move ahead in your own journeys of research and engagement—journeys in which you take risks, open up questions, create more experiences than can be integrated at first sight, require support, and generate personal and professional change.