CYCLES and EPICYCLES of ACTION RESEARCH

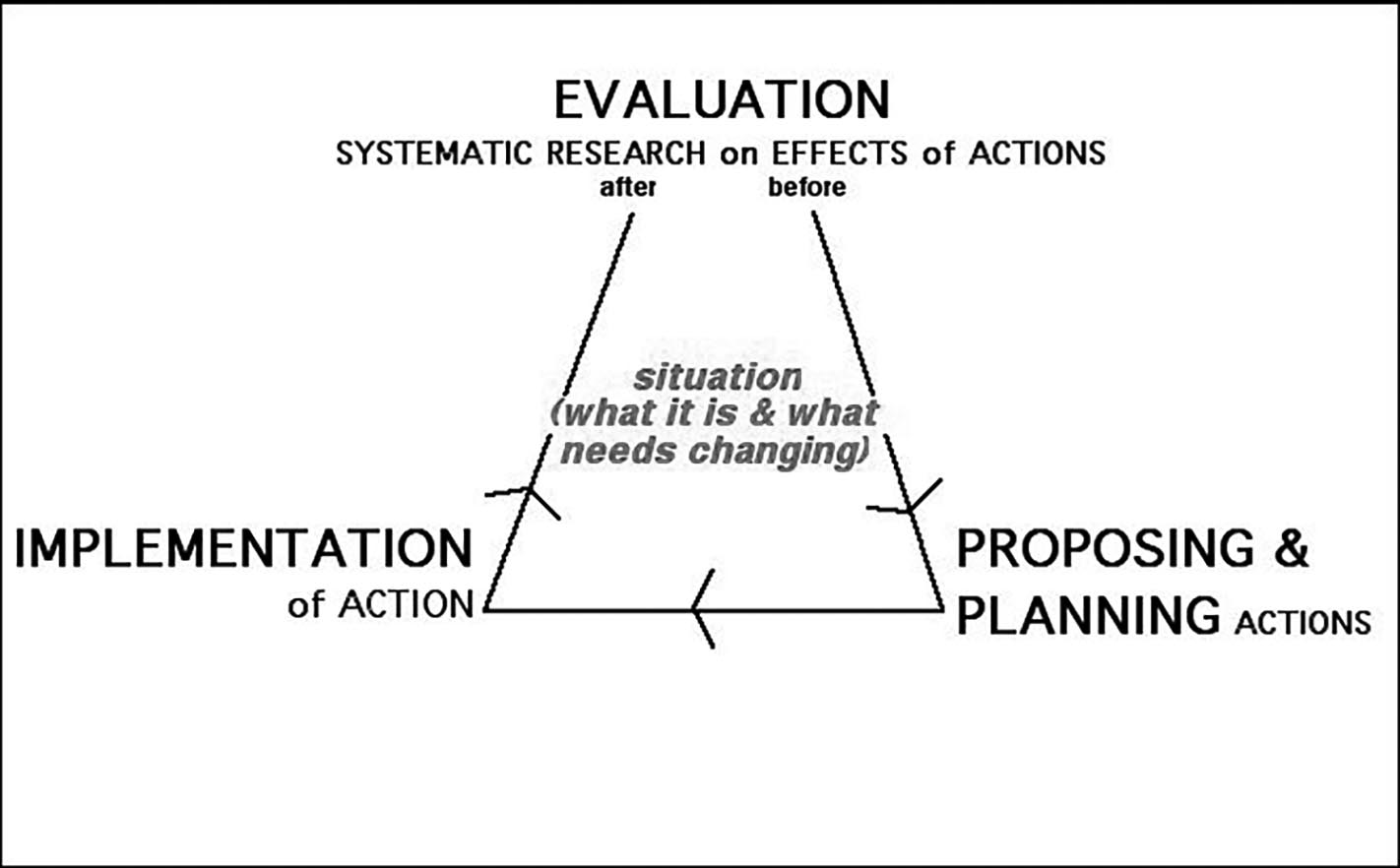

Action Research begins when you (as an individual or as a group) want to do something to change the current situation, that is, to take action. “Action” can refer to many different things: a new or revised curriculum; a new organizational arrangement, policy, or procedure in educational settings; equivalent changes in other professions, workplaces, or communities; changes in personal practices, and so on. Action Research traditionally progresses from evaluations of previous actions through stages of planning and implementing some action to evaluation of its effects, that is, research to show what ways the situation after the action differs from the way it was before. This cycle of Action Research is conveyed in the following figure.

The basic cycle of Action Research

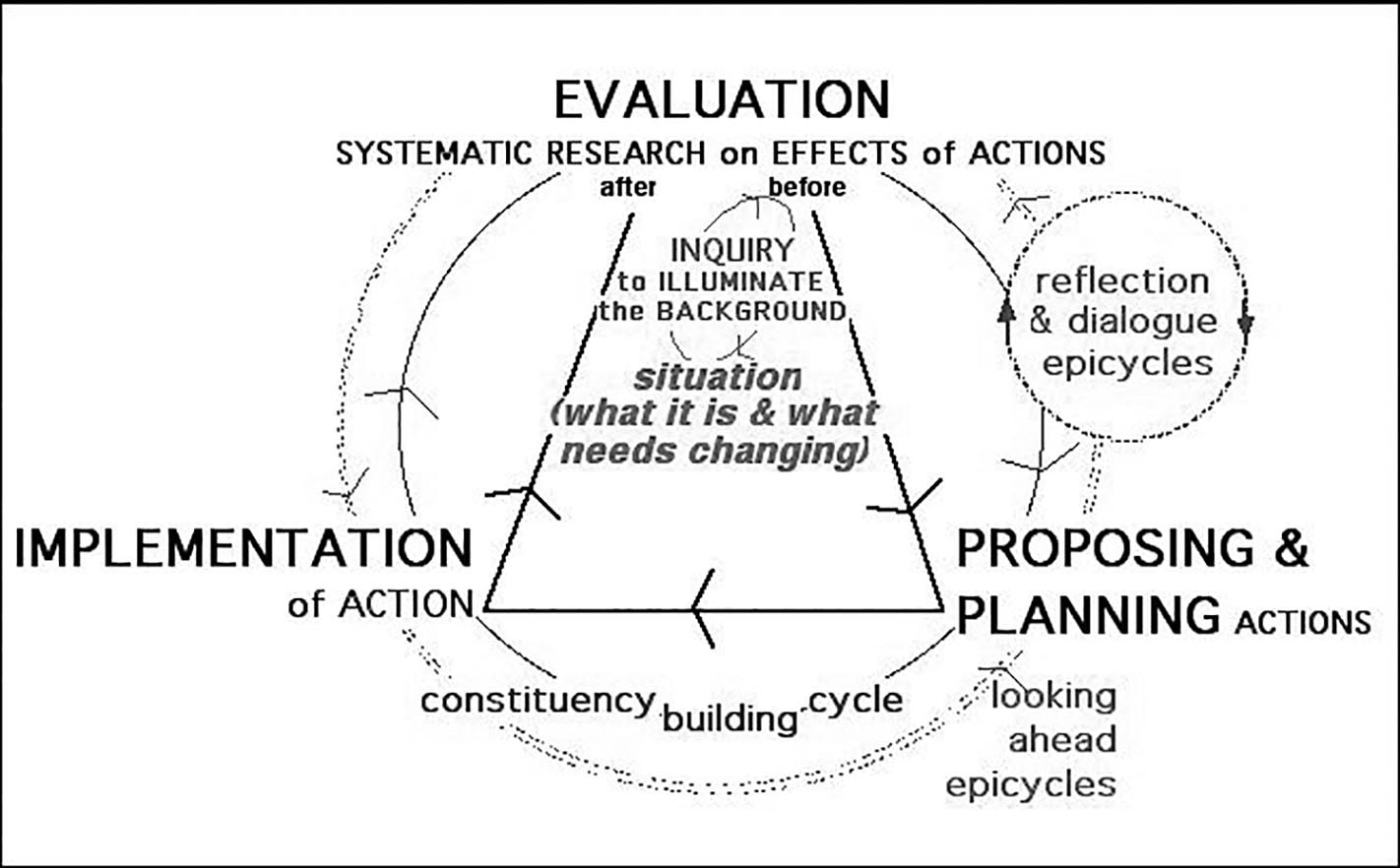

To this basic cycle of Action Research we can add reflection and dialogue through which you review and revise the ideas you have about what action is needed as well as your ideas about how to build a constituency to implement the change. Your thinking about what the situation is and what needs changing can also be altered by inquiring into the background (e.g., what motivates you to change this situation?) as well as looking ahead to future stages. Just like the basic cycle of Action Research, constituency building happens over time, so we can think of this a second cycle. The other additions above, however, often make us go back and revisit what had seemed clear and settled, so we can call these the epicycles (i.e., cycles on top of cycles) of Action Research. The composite of all these factors is conveyed in the following figure. (See also Taylor 2009 for a step-by-step presentation.)

The Cycles and Epicycles of Action Research

Below we expand on this introduction then elaborate on the key aspects of Action Research. After that follows a list of tools and processes useful in the different aspects of Action Research. In Part 3 the use of various tools and processes is illustrated by excerpts from a semester-long project by Jeremy on designing Collaborative Play by Teachers in Curriculum Planning. A think-piece in Part 4 on Action Research and Participation places our approach in a wider context. We recognize that the exposition to follow is brief—a summary more than a detailed guide. We believe that the interplay between the cycles and epicycles will become clear primarily through experience conducting Action Research and through practice using the tools.

Elaboration on the Introduction to Action Research

Action Research begins, as noted above, when you (as an individual or as a group) want to do something to change the current situation, that is, to take action towards educational, organizational, professional, or personal change. (The complementary Phases framework emphasizes research and writing that prepares you to communicate with an audience.) To move from some broad idea of the action you think is needed to a more refined and do-able proposal, you may need to review evaluations of the effects of past actions (including possibly evaluations of actions you have previously made) and to conduct background inquiry so you can take into account other relevant considerations (e.g., who funds or sponsors these kinds of changes and evaluations).You also have to get people—yourself included—to adopt or adapt your proposals, that is, you have to build a constituency for any actions. Constituency building happens in a number of ways: when you draw people into reflection, dialogue, and other participatory processes in order to elicit ideas about the current situation, clarify objectives, and generate ideas and plans about taking action to improve the situation; when people work together to implement actions; and when people see evaluations of how good the actions or changes were in achieving the objectives. Evaluation of the effects of an action or change can lead to new or revised ideas about further changes and about how to build a constituency around them, thus stimulating ongoing cycles of Action Research.

These cycles are not a steady progression of one step to the next. Reflection and dialogue epicycles at any point in the cycle can lead to you to revisit and revise the ideas you had about what change is needed and about how to build a constituency to implement the change. Revision also happens when, before you settle on what actions to pursue, you move “backwards” and look at evaluations of past actions and conduct other background inquiry. Revision can also happen when you look ahead at what may be involved in implementing or evaluating proposed actions or in building a constituency around them. Such looking ahead is one of the essential features of planning.

In summary, Action Research involves evaluation and inquiry, reflection and dialogue, constituency building, looking ahead, and revision in order to clarify what to change, to get actions implemented, to take stock of the outcomes, and to continue developing your efforts.

Of course, as is the case with all evaluations and with research more generally, there is no guarantee that the results of Action Research will influence relevant people and groups (the so-called “stakeholders”). However, constituency building—including dialogue and reflection on the implications of the results—provides a good basis for mobilizing support and addressing potential opposition in the wider politics of applied research and evaluation.

Elaboration on the Aspects of Action Research

Evaluation is the systematic study of the effects of actions. Evaluations may be of actions taken before you got involved or in another setting as well as actions you implement. You can use evaluations to design new or revised actions and to convince others to implement equivalent actions in other settings. To establish the specific effect of a specific action you need to compare two situations—one in which the action is taken and one in which it is not, with nothing else varying systematically between the two situations. Such a comparison may be hard to find or achieve. In any case, tightly focused evaluations need to be complemented by broader inquiry to clarify for yourself what warrants change given what is known about this situation and others like it and to clarify what a potential constituency might be.

Constituency building involves getting others to adopt or adapt your action proposals, or, better still, enlisting others to become part of the “you” that shapes, evaluates, and revises any proposals. Adoption or adaptation is helped by succinct presentations to a potential constituency about the action proposals and the evaluations and inquiry that supports them. Enlistment of others is helped by well-facilitated participation of stakeholders in the initial evaluation and inquiry, in formulation of action proposals, and in planning so as to bring about their investment in implementing the proposals. If the actions are personal changes and the constituency is yourself, you can still facilitate your own evaluation and planning process to ensure your investment in the actions. Indeed, constituency building for any action begins with yourself. In order to contribute effectively to change, you need to be engaged—to have your head, heart, hands, and human connections aligned. You need to pay attention to what help you need to get engaged and stay so.

Reflection and dialogue happen in a variety of activities (see, e.g., tools useful for Action Research below and Reflective Practitioner Goals). However, the quality they share is making space to listen to yourself and others so that thoughts about an issue can emerge that had been below the surface of your attention or come into focus. Reflection and dialogue are valuable in Action Research for these reasons, among others: ongoing revision of your ideas about the current situation; generating action proposals; and drawing more people into your constituency. Through reflection and dialogue you can check that the evaluation and inquiry you undertake about the current situation and past actions relate well to possible actions you are considering and to the constituencies you intend to build. You can check that the results of your evaluations and inquiry support the actions and constituency building you pursue. You can review what actually happens when an action is implemented and its effects are evaluated and, on that basis, generate ideas for the next cycle of Action Research.

Planning involves looking ahead at what may be involved before you settle on what actions to pursue. Planning is strategic when action proposals respect the resources—possibly limited—that you and others in your constituency have and when the planning process elicits people's investment in implementation of those actions.

Taylor, P. J. (2009). Step-by-step presentation of the Cycles and Epicycles framework of Action Research. http://www.faculty.umb.edu/ peter_taylor/ARcycling2.html (viewed 28 Nov 2011)