The End of Europe's Middle Ages

This chapter is composed of five sections: Introduction, England, France, Spain, and Portugal. Please follow the link at the end of each section to read the entire chapter.

England

Although England's island location defined its geographic boundaries, attempts were made to retain English territories on the Continent. These attempts met with limited success and virtually all Continental holdings were lost during the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453) with France. These losses would ultimately benefit the English since England could now focus on its home front without overextending its resources.

England's relative geographical isolation also allowed its political structures to evolve virtually unhampered by external powers, making it possible for civil and legal institutions to be standardised throughout the country. Regional interests were limited by officials who represented the Crown. However, the English king did not rule absolutely. Most laws and tax levies required parliamentary approval to pass.

|

A Brief History of the English Parliament |

During the fourteenth century, the English Parliament became a permanent institution that was split into two parts, the House of Commons and the House of Lords. While the House of Lords was composed of the great prelates and magnates, the Commons was made up of representatives of townspeople and petty knights. Although the Commons made significant gains during the Hundred Years' War when fiscal support was traded for political concessions from the monarchy, the Commons had not yet become an independent voice. Royal and aristocratic interests remained at the forefront during the late Middle Ages.

Longstanding territorial disputes between England and France erupted in the early fourteenth century when the last Capetian king of France died without male issue in 1328. Edward III of England (1312-1377) claimed the French crown through his mother, the daughter of Philip IV the Fair (1268-1314). The French were appalled at the idea of an English monarch and raised Philip of Valois (1293-1350), the son of Philip the Fair's younger brother, to the throne as Philip VI. Edward III initially accepted Philip VI as king of France but simmering hostilities between the two nations led him to revive his claim in 1337 and initiate the Hundred Years' War.

|

Hundred Years' War (1337-1453) |

The English initially enjoyed success in their military ventures, winning decisive victories at

Crécy in 1346 and at

Poitiers in 1356. When Edward III died in 1377, his successor,

Richard II (1367-1400) ignored the war on the Continent and focussed on reducing the power of the English aristocracy. This attack against their authority alarmed the English nobility and, with the sanction of Parliament, Richard II was deposed in 1399. Parliament elected

Henry IV (1367-1413) as king but troubles in England occupied him for most of his reign. This incident demonstrates the power and limitations of Parliament during the late Middle Ages. Even though the Houses merely confirmed the wishes of the magnates, these great lords appreciated the importance of receiving parliamentary approval for their actions.

|

Hostilities with France resumed in 1415 under Henry V (1387-1422) who won a significant victory at Agincourt in the same year. His alliance in 1416 with Sigismund, the Holy Roman emperor, split the French defences and Henry V continued to win French lands. In 1420, a peace treaty with Charles VI of France was concluded at Troyes. Henry V returned to France in 1421 to suppress a French rebellion but he became ill and died at Vincennes in 1422, leaving an infant son as heir. The death of Henry V marked a turning point in the Hundred Years' War and, by 1453, England no longer held any Continental lands except Calais. |

|

Henry V - William Shakespeare |

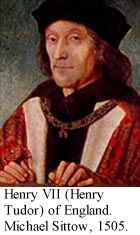

The Hundred Years' War had barely ended when a series of dynastic wars split England. The Wars of the Roses (1455-1485) were fought between the rival houses of Lancaster and York, each claiming the English crown. Neither side was able to gain long-term ascendancy until, in 1485, the Yorkist claim ended when Richard III (1452-1485) was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field. The Lancastrian leader, Henry Tudor (1457-1509), ascended to the throne as Henry VII. His marriage to Elizabeth, the daughter of the Yorkist king, Edward IV (1442-1483), united the warring houses and established the Tudor dynasty that would provide the rulers to lead England into the next century.

|

The Wars of the Roses |

|

Return to New Monarchies: Introduction | Proceed to New Monarchies: France |

|

The End of Europe's Middle Ages / Applied History Research Group / University of Calgary

Copyright © 1998, The Applied History Research Group