CREATIVITY-IN-CONTEXT

In 2013, when Peter and Jeremy co-taught an experimental version of the core course on Creative Thinking for the CCT graduate program, Peter explored a shift of emphasis from creativity as people coming up with novel and useful or adaptable products to people engaging in the processes-in-context that support creativity as processes-in-context. The measure of creativity in this sense is not the quantity or quality of products, but your thinking and feeling, every day or every moment, that it is no longer possible for yourself to simply continue along previous lines. (These notes refer back to schemas and text from previous passages.)

1. Creativity as processes-in-context

An individual's creativity happens and is recognized in some context. Indeed, shaping the relevant context provides additional opportunities for an individual's creativity. An individual's context-shaping efforts, in turn, influence the creative pursuits of others. Such ongoing Intersecting Processes are depicted schematically here:

Intersecting processes around creation of some focal outcome

Intersecting processes around creation of some focal outcome

In the schema the dashed lines indicate the effect of the tools and processes you employ or are involved in; key points of engagement to shape the processes and their intersections are depicted by *; and the circles and ovals depict features that are, at least for a time, visible to all and reliable. There is, of course, an inner, less-visible strand of a person's body and mind.

I am suggesting a shift of emphasis, which I explore in this set of principles, from novel and useful or adaptable products (in the schema: “focal outcomes”) to your engaging in the processes-in-context that supports creativity as processes-in-context. The measure of creativity in this sense is not the quantity or quality of products but your thinking-feeling, every day or every moment, that it is no longer possible for yourself to simply continue along previous lines.

(There are many sets of tools offered to help people be creative in the sense of coming up with novel and useable ideas, whether those tools are meant for a specific domain only or more generally; see Plsek 1997 for an entry point. However, the critical thinker in me always wants to understand things by holding them in tension with alternatives [see think-piece—Journeying to Develop Critical Thinking], thus the shift of emphasis explored here.)

2. Persistent plus-delta

The schema in #1 is abstract: It does not refer to any specific person, context, activity, or domain. The second principle makes you ground your development of creativity in the specifics of your own situation.

If you are simply continuing along previous lines in some or many domains of your work and life, then how do you bootstrap yourself into developing creativity in those domains? Suggestion: Have someone do a Plus-Delta Feedback at the end of any activity you are involved in and hope that the experience will—eventually if not the first time— lead you to make Plus-Delta Feedback into a routine. Paying attention to the things you appreciated (the plus) makes it more likely that you—or the people responsible for the activity you are evaluating—will work on the things that need improving or changing (the delta). Eventually, something that arose as a delta becomes a plus and you are ready for some further deltas. As Vivian Paley (2010, 25), a long-time teacher and observer of kindergarten classes, notes: “When [children] solve one problem, they create another to act on.” We might add: a problem that they had not been able to see before. The result is ongoing development, which one of her students, a new learner of English, expressed well: “Story of chapters. Once a time chapter is one and the end is coming. Until the cock crows. To be continued ha ha!” (Paley 1997, 95). Or, from a conversation between Paley and her assistant (p. 47):

Paley: “Isn’t it a great feeling, to be tying together all the stories.” Nisha: “Yes, but it doesn’t feel as if I’m tying things up. No, it's more like opening up, or maybe discovering things I’ve forgotten.”

3. Address, not suppress, the complexities of processes-in-context

Process-in-context, as the figure in #1 intentionally depicts, is complex; it is distributed beyond any individual's control. (Indeed, the principles to follow add further complexity.) It is possible to try to suppress that distributed complexity using simple principles, such as “promote the power for an individual of positive thinking.” However, a variant of Plus-Delta Feedback of your own efforts allows you to address the complexities: Identify a manageable set of criteria, say, 5-10 items that you are prepared to focus on. (Too many items and none get much attention or it is too time consuming to keep evaluating your performance regularly.) The Plus-Delta Feedback for each criterion might be done by an observer or it might be done by you directly after the activity being evaluated (Freeman 1999, 55-59). This approach assumes that you, or the person you ask to evaluate you, have ideas about ways to improve (in contrast with conventional rubrics used in education; Taylor 2011). If some issue arises that you do not know how to address, having done Plus-Delta Feedback puts you in a good position—in terms of rich detail about the activity being evaluated and in terms of your emotional state—to raise the issue for discussion with someone who might have more experience or ideas.

4. Jostling in taking initiative in and through relationships

Developing creativity unavoidably raises tensions among the six different aspects of Taking Initiative In and Through Relationships. If inhabiting the “mandala” of the six aspects looks complicated or unsettled, Plus-Delta Feedback, as suggested in #3, might help. At the end of any activity, you would complete the Plus-Delta for each of the six aspects. Presumably, if you focus on one or two of the aspects during the activity, there will be room for deltas on the others. At the same time, the pluses for the aspects on which you did focus will provide a base of confidence from which to pay attention to the others.

5. Self-direction and community support: A suite of schemas

The mandala mentioned in #4 includes self-direction (taking initiative) and community support (through relationships), then combines them (taking initiative in relationships). To speak of being self-directed or contributing to a community that supports others (and yourself) is to presuppose that you have already bootstrapped yourself into beginning to develop your creativity. If that is not the case, go back to #2. If you have been developing your creativity, but are now trying to motivate change in people who seem settled in continuing along previous lines, you can expect to have to stay with them as they jostle among the aspects of #4. The challenge of doing that is not, however, addressed directly in the suite of schemes to follow. Instead, the focus here is on your own creativity development. Each schema is intended to be taken up when you see it as relevant to you. But keep in mind at all times that you should expect to jostle among the six aspects of Taking Initiative In and Through Relationships (#4) as you engage in the processes-in-context that supports creativity as processes-in-context. Moreover, Plus-Delta Feedback (#2) can provide direction at the scale of small steps even when the grand direction for your work or life remains not yet clear.

Another way of saying this is that each of us navigates the distributed complexity (#1) in part by trying to impart order according to our sense of our self—our identity, aspirations or goals, and will to choose among goals and move towards them. We achieve some goals and then have greater capacity, knowledge, skills, plans, and direction to keep moving and developing. We also encounter setbacks and we revise our goals. Indeed, our self-directedness can be buffeted or even threatened by the order-imparting efforts of other people navigating their own distributed complexities. Yet relationships with others are a source of resources and support (material, emotional, etc.) from outside ourselves that help shape how far and in what directions our movement and development happens. Relationships are also a source of unplanned conjunctions or intersections that we draw from. Such connections can help us to not simply continue along previous lines and, at the same time, to clarify our sense of directedness as individuals.

My current ideal is to be involved in communities of adults that have the feel of Vivian Paley's kindergarten classrooms: “I need the intense preoccupation of a group of children and teachers inventing new worlds as they learn to know each other's dreams” (Paley 1997, 50). “Kindergartners are passionate seekers of hidden identities and quickly respond to those who keep unraveling the endless possibilities” (p. 4); they “search for the mirror of self-revelation” (p. 8).

5a. Persistent exploration, serendipity, identity formation-in-relationship

Persistence in exploring makes serendipity more likely; the unintended connections—the unplanned conjunctions in #5—help clarify our sense of directedness or our identity. What is exploration? A: Paying attention and learning about things that are unfamiliar. If “things” are taken to include strands of oneself (thinking, body, skills, etc.), other people, materials or media, or topics (areas of knowledge), then exploration of each thing is connected to the exploration of the others. Why explore? A: It can be rewarding in the sense of expanding our identity—who we are and what we are capable of—whether directly or through serendipitous connections—and this experience reinforces our persistence in exploring. Indeed, each point in the schema reinforces the others. This is necessary given that exploration, like a journey into unfamiliar or unknown areas, involves risk, opens up questions, creates more experiences than can be integrated at first sight, requires support, and yields personal change (see Journeying to Develop Critical Thinking).

Persistent exploration, serendipity, identity formation-in-relationship

Persistent exploration, serendipity, identity formation-in-relationshipb. Learning: critical thinking, creative thinking & reflective practice

Exploration in #5a centers on learning. This next schema captures four interacting aspects of learning of a kind that combines critical thinking, creative thinking and reflective practice.

Learning that combines critical thinking, creative thinking and reflective practice

Learning that combines critical thinking, creative thinking and reflective practice

“Connect” here refers first to the inter-personal—the “horizontal connections” and “explore difference” aspects of Taking Initiative In and Through Relationships (#4). Paying attention to difference provides a source of alternatives to your own perspectives or practices, alternatives that allow you to understand something by holding it in tension with alternatives, i.e., to “Puzzle.” That, in turn, prepares you to put the alternatives into practice—“Create Change”— take stock of the outcomes—“Reflect”—and revise your approaches accordingly—further Change Creation. Reflection on any new understandings from Puzzling also pave the way for making Connections of additional kinds, namely, conceptual and intra-personal, as well as strengthening the inter-personal Connections that support you as you take risks in Creating Change, opening up questions—Puzzling—and “create more experiences than can be integrated at first sight.”

c. Many Rs

The preceding schema is teased out into more elements in the Many Rs schema (see think-piece on Teaching and Learning For Reflective Practice). This is designed to convey that a) some Rs further down will make limited sense until more basic Rs higher up have been internalised and b) opening-out periods alternate with periods of consolidating experiences to date. On the first point, a slight variant of Plus-Delta Feedback is called for. At the end of an extended period—say, six months—you would not consider all the Rs, but only those that have meaning for you. The meaning of the Rs may well have evolved since the previous time you stopped to take stock. Putting both points together, you can expect the flow of your development to be windy and less than direct.

In this last sense the schema of many Rs stands as a counterpoint to Wiggins and McTighe's (2005) popular idea of backward design in curriculum, wherein the teacher identifies desired results; determines acceptable evidence of students achieving those results; plans learning experiences and instruction accordingly, making explicit the sought-after results and evidence. The Many Rs schema, just as in the previous one about learning (#5b) and Taking Initiative In and Through Relationships (#4), provide guidance for any individual, such as a teacher, in your efforts to shape the context for developing creativity of yourselves or others. Context-shaping is the focus of the remaining schemas.

d. 4Rs

The 4Rs sequence of conditions that make interactions among participants transformative also make a context, such as a workshop or classroom, conducive of creativity development.

e. Combo

Combining the mandala of #4 with #5a, b, and d yields the following schema.

Combination of previous schemas

Combination of previous schemas

Notice: a) persistence is motivated by the positive experience of re-engagement—once you are bootstrapped into developing creativity, a well-shaped context can make the development, in successive cycles of this schema, self-fueling; b) the packing of items around the first two Rs, where the third R, Revelation, might correspond to the product of creativity under the conventional framing; and c) the four-way connections in the central schema (drawn from #5b) suggest that the 4Rs might be better thought of in four-way connections than as a unidirectional swoosh.

f. Criteria and conditions for a successful workshop

If you are trying to shape the context for creativity development, you could adopt the model of workshop organizers who, aiming to improve their efforts, do Plus-Delta Feedback of the criteria and conditions for a successful workshop (taking into account the ways that certain conditions are conducive of others; see think-piece on Teaching and Learning For Reflective Practice).

g. Context beyond the familiar

The following schema could inform your work when you are ready for your context-shaping to move beyond the container of a classroom or workshop into unfamiliar situations in which you work with diverse people.

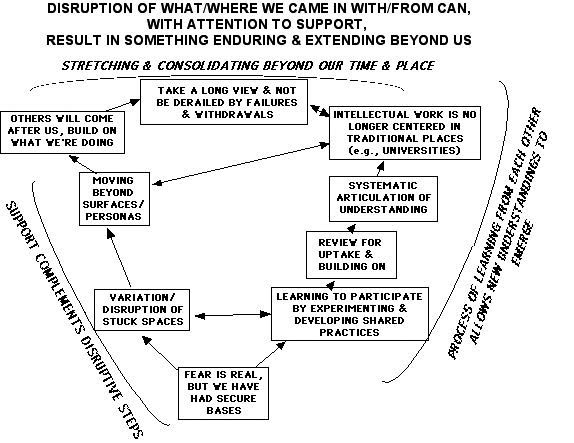

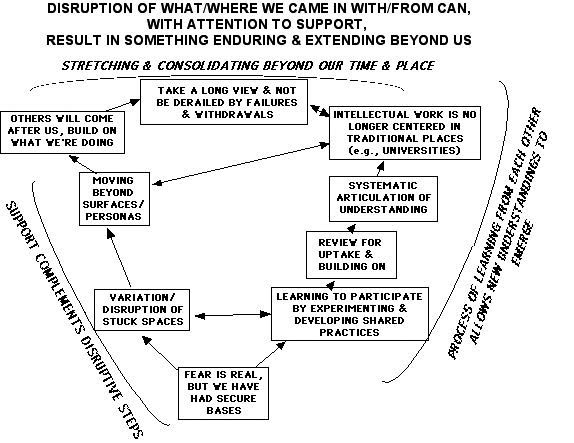

Structural model of the conditions for working with diverse people beyond the traditional boundaries of the university (see text for explanation)

Structural model of the conditions for working with diverse people beyond the traditional boundaries of the university (see text for explanation)

The themes correspond to clusters of conditions that emerged from a group Future-Ideal-Retrospective activity (Taylor 2010) in which a group of university researchers addressed “the challenge of bringing into interaction not only a wider range of researchers, but a wider range of social agents, and to the challenge of keeping them working through differences and tensions until plans and practices are developed in which all the participants are invested” (Taylor 2005, 199). The themes were then subject to back-of-the-envelope “interpretive structural modeling,” in which the cluster is lower in the diagram and linked to a cluster above it if addressing or acknowledging the consideration reflected in the first cluster makes it easier to address the consideration reflected in the second cluster (see item f above).

"To be continued ha ha!”

References

Freeman, K. A. (1999). Inviting Critical and Creative Thinking into the Classroom. Critical & Creative Thinking Program Capstone Collection. https:// scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_capstone/113/ (viewed 19 Sep 2018).

Paley, V. G. (1997). The Girl with the Brown Crayon. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Paley, V. G. (2010). The Boy on the Beach: Building Community by Play. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Plsek, P. E. (1991). “The Three Basic Principles Behind All Tools for Creative Thinking: Attention, Escape, and Movement.” http://www.directed creativity.com/pages/Principles.html (viewed 11 Sep 2018).

Taylor, P. J. (2010). “Collaboration among diverse participants.” https:// wp.me/pPWGi-t (viewed 18 Sep 2018).

Taylor, P. J. (2011). “Moving beyond conventional rubrics.” http:// wp.me/p1gwfa-nR (viewed 11 Sep 2018).

Wiggins, G. P. and J. McTighe (2005). Understanding by Design. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.