From Bondage to Freedom

HUMAN infirmity in moderating and checking the emotions I name bondage: for, when a man is a prey to his emotions, he is not his own master, but lies at the mercy of fortune: so much so, that he is often compelled, while seeing that which is better for him, to follow that which is worse. (Ethics, Book 4, Preface)

The Passions

Spinoza's Remedy for Our Domination by the Passions

Note to Proposition XX, Book 5 of The Ethics

I have gone through all the remedies against the emotions, or all that the mind, considered in itself alone, can do against them. Whence it appears that the mind's power over the emotions consists:— I. In the actual knowledge of the emotions (V. iv note). II. In the fact that it separates the emotions from the thought of an external cause, which we conceive confusedly (V. ii. and iv. note). III. In the fact, that, in respect to time, the emotions referred to things, which we distinctly understand, surpass those referred to what we conceive in a confused and fragmentary manner (V. vii.). IV. In the number of causes whereby those modifications, are fostered, which have regard to the common properties of things or to God (V. ix. xi.). V. Lastly, in the order wherein the mind can arrange and associate, one with another, its own emotions (V. x. note and xii. xiii. xiv.). But, in order that this power of the mind over the emotions may be better understood, it should be specially observed that the emotions are called by us strong, when we compare the emotion of one man with the emotion of another, and see that one man is more troubled than another by the same emotion; or when we are comparing the various emotions of the same man one with another, and find that he is more affected or stirred by one emotion than by another. For the strength of every emotion is defined by a comparison of our own power with the power of an external cause. Now the power of the mind is defined by knowledge only, and its infirmity or passion is defined by the privation of knowledge only: it therefore follows, that that mind is most passive, whose greatest part is made up of inadequate ideas, so that it may be characterized more readily by its passive states than by its activities: on the other hand, that mind is most active, whose greatest part is made up of adequate ideas, so that, although it may contain as many inadequate ideas as the former mind, it may yet be more easily characterized by ideas attributable to human virtue, than by ideas which tell of human infirmity. Again, it must be observed, that spiritual unhealthiness; and misfortunes can generally be traced to excessive love for something which is subject to many variations, and which we can never become masters of. For no one is solicitous or anxious about anything, unless he loves it; neither do wrongs, suspicions, enmities, &c. arise, except in regard to things whereof no one can be really master. We may thus readily conceive the power which clear and distinct knowledge, and especially that third kind of knowledge (II. xlvii. note), founded on the actual knowledge of God, possesses over the emotions: if it does not absolutely destroy them, in so far as they are passions (V. iii. and iv. note); at any rate, it causes them to occupy a very small part of the mind (V. xiv.). Further, it begets a love towards a thing immutable and eternal (V. xv.), whereof we may really enter into possession (II. xlv.); neither can it be defiled with those faults which are inherent in ordinary love; but it may grow from strength to strength, and may engross the greater part of the mind, and deeply penetrate it.

|

Practical Precepts

By [the] power of rightly arranging and associating the bodily modifications we can guard ourselves from being easily affected by evil emotions. For (V. vii.) a greater force is needed for controlling the emotions, when they are arranged and associated according to the intellectual order, than when they are uncertain and unsettled. The best we can do, therefore, so long as we do not possess a perfect knowledge of our emotions, is to frame a system of right conduct, or fixed practical precepts, to commit it to memory, and to apply it forthwith to the particular circumstances which now and again meet us in life, so that our imagination may become fully imbued therewith, and that it may be always ready to our hand. For instance, we have laid down among the rules of life (IV. xlvi. and note), that hatred should be overcome with love or high-mindedness, and not required with hatred in return. Now, that this precept of reason may be always ready to our hand in time of need, we should often think over and reflect upon the wrongs generally committed by men, and in what manner and way they may be best warded off by high-mindedness: we shall thus associate the idea of wrong with the idea of this precept, which accordingly will always be ready for use when a wrong is done to us (II. xviii.). If we keep also in readiness the notion of our true advantage, and of the good which follows from mutual friendships, and common fellowships; further, if we remember that complete acquiescence is the result of the right way of life (IV. lii.), and that men, no less than everything else, act by the necessity of their nature: in such case I say the wrong, or the hatred, which commonly arises therefrom, will engross a very small part of our imagination and will be easily overcome; or, if the anger which springs from a grievous wrong be not overcome easily, it will nevertheless be overcome, though not without a spiritual conflict, far sooner than if we had not thus reflected on the subject beforehand. As is indeed evident from V. vi. vii. viii. We should, in the same way, reflect on courage as a means of overcoming fear; the ordinary dangers of life should frequently be brought to mind and imagined, together with the means whereby through readiness of resource and strength of mind we can avoid and overcome them. But we must note, that in arranging our thoughts and conceptions we should always bear in mind that which is good in every individual thing (IV. lxiii. Coroll. and III. lix.), in order that we may always be determined to action by an emotion of pleasure. For instance, if a man sees that he is too keen in the pursuit of honour, let him think over its right use, the end for which it should be pursued, and the means whereby he may attain it. Let him not think of its misuse, and its emptiness, and the fickleness of mankind, and the like, whereof no man thinks except through a morbidness of disposition; with thoughts like these do the most ambitious most torment themselves, when they despair of gaining the distinctions they hanker after, and in thus giving vent to their anger would fain appear wise. Wherefore it is certain that those, who cry out the loudest against the misuse of honour and the vanity of the world, are those who most greedily covet it. This is not peculiar to the ambitious, but is common to all who are ill-used by fortune, and who are infirm in spirit. For a poor man also, who is miserly, will talk incessantly of the misuse of wealth and of the vices of the rich; whereby he merely torments himself, and shows the world that he is intolerant, not only of his own poverty, but also of other people's riches. So, again, those who have been ill received by a woman they love think of nothing but the inconstancy, treachery, and other stock faults of the fair sex; all of which they consign to oblivion, directly they are again taken into favour by their sweetheart. Thus he who would govern his emotions and appetite solely by the love of freedom strives, as far as he can, to gain a knowledge of the virtues and their causes, and to fill his spirit with the joy which arises from the true knowledge of them: he will in no wise desire to dwell on men's faults, or to carp at his fellows, or to revel in a false show of freedom. Whosoever will diligently observe and practice these precepts (which indeed are not difficult) will verily, in a short space of time, be able, for the most part, to direct his actions according to the commandments of reason.

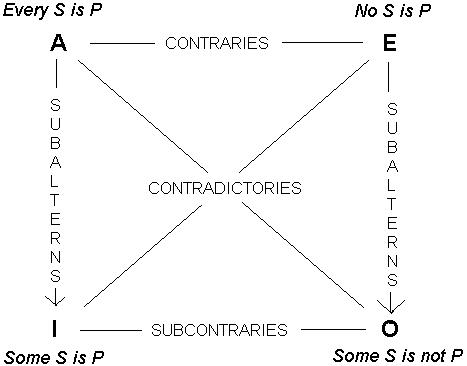

The Three Kinds of Knowledge

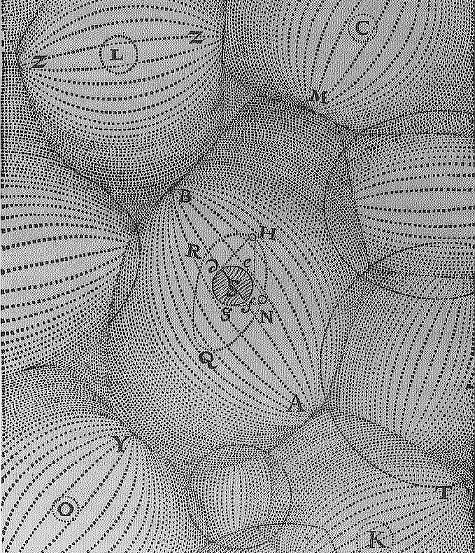

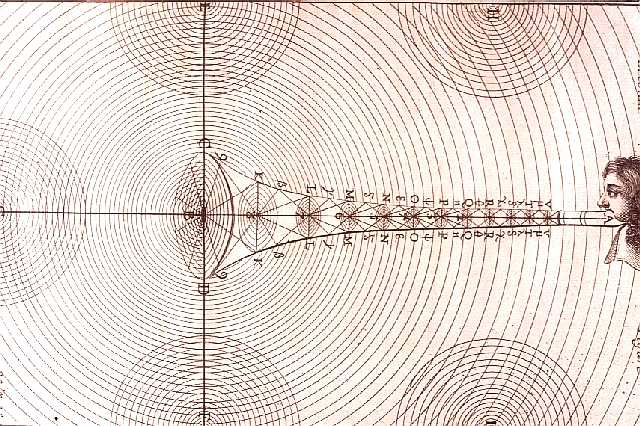

I will illustrate all three kinds of knowledge

by a single example. Three numbers are given for finding a fourth, which shall

be to the third as the second is to the first. Tradesmen without hesitation

multiply the second by the third, and divide the product by the first; either

because they have not forgotten the rule which they received from a master

without any proof, or because they have often made trial of it with simple

numbers, or by virtue of the proof of the nineteenth proposition of the seventh

book of Euclid, namely, in virtue of the general property of proportionals.

But with very simple numbers there is no need of this. For instance, one,

two, three, being given, everyone can see that the fourth proportional is six;

and this is much clearer, because we infer the fourth number from an intuitive

grasping of the ratio, which the first bears to the second.

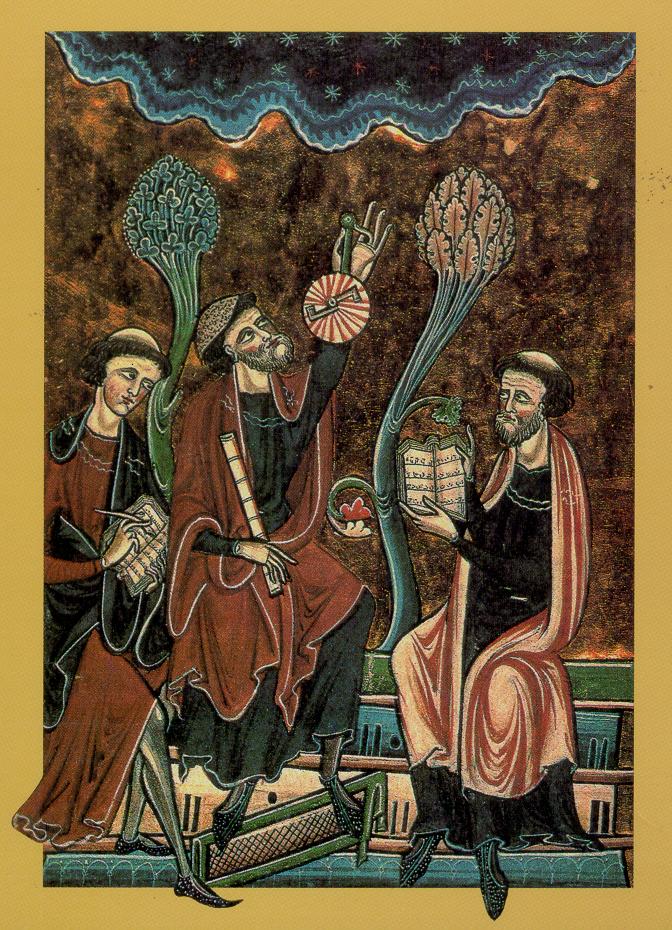

Knowledge of the First Kind - Sensation, Imagination, Hearsay, Signs

Knowledge of the Second Kind - Logical, Scientific, and Mathematical Reasoning

\

\

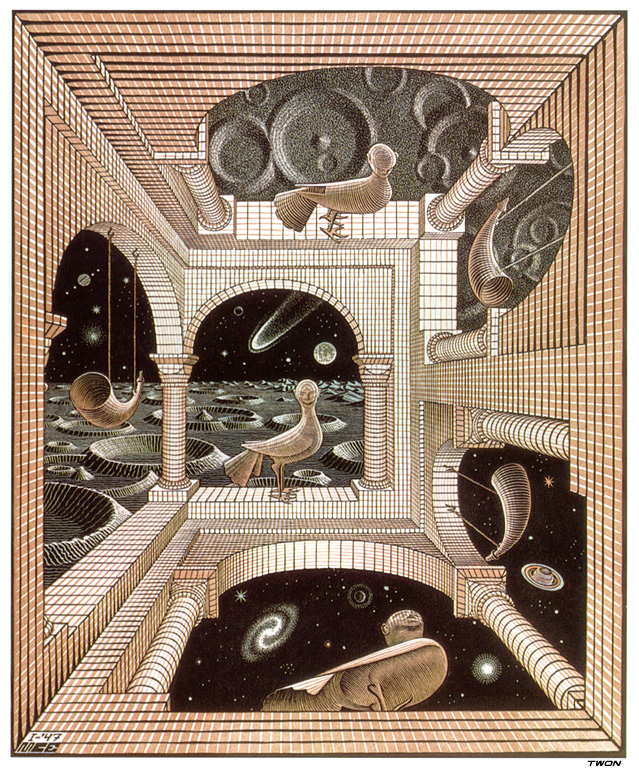

Knowledge of the Third Kind - Immediate Intuitive Grasp of Essences and Their Origin in Infinite Substance

PROP. XXV. The highest endeavour of the mind, and the highest virtue is to understand things by the third kind of knowledge.

Proof.--The third kind of knowledge proceeds from an adequate idea of certain attributes of God to an adequate knowledge of the essence of things (see its definition II. xl. note ii.); and, in proportion as we understand things more in this way, we better understand God (by the last Prop.); therefore (IV. xxviii.) the highest virtue of the mind, that is (IV. Def. viii.) the power, or nature, or (III. vii.) highest endeavour of the mind, is to understand things by the third kind of knowledge. Q.E.D.

Freedom in Community

Appendix to The Ethics, Book 4

|

WHAT I have said in this Part concerning the right way of life has not been arranged, so as to admit of being seen at one view, but has been set forth piece-meal, according as I thought each Proposition could most readily be deduced from what preceded it. I propose, therefore, to rearrange my remarks and to bring them under leading heads. I. All our endeavours

or desires so follow from the necessity of our nature, that they can be

understood either through it alone, as their proximate cause, or by virtue

of our being a part of nature, which cannot be adequately conceived

through itself without other individuals. II. Desires, which

follow from our nature in such a manner, that they can be understood

through it alone, are those which are referred to the mind, in so far as

the latter is conceived to consist of adequate ideas: the remaining

desires are only referred to the mind, in so far as it conceives things

inadequately, and their force and increase are generally defined not by

the power of man, but by by the power of things external to us: wherefore

the former are rightly called actions, the latter passions, for the former

always indicate our power, the latter, on the other hand, show our

infirmity and fragmentary knowledge. III. Our actions,

that is, those desires which are defined by man's power or reason, are

always good. The rest may be either good or bad. IV. Thus in life it is

before all things useful to perfect the understanding, or reason, as far

as we can, and in this alone man's highest happiness or blessedness

consists, indeed blessedness is nothing else but the contentment of

spirit, which arises from the intuitive knowledge of God: now, to perfect

the understanding is nothing else but to understand God, God's attributes,

and the actions which follow from the necessity of his nature. Wherefore

of a man, who is led by reason, the ultimate aim or highest desire,

whereby he seeks to govern all his fellows, is that whereby he is brought

to the adequate conception of himself and of all things within the scope

of his intelligence. V. Therefore, without

intelligence there is not rational life: and things are only good, in so

far as they aid man in his enjoyment of the intellectual life, which is

defined by intelligence. Contrariwise, whatsoever things hinder man's

perfecting of his reason, and capability to enjoy the rational life, are

alone called evil. VI. As all things

whereof man is the efficient cause are necessarily good, no evil can

befall man except through external causes; namely, by virtue of man being

a part of universal nature, whose laws human nature is compelled to obey,

and to conform to in almost infinite ways. VII. It is

impossible, that man should not be a part of nature, or that he should not

follow her general order; but if he be thrown among individuals whose

nature is in harmony with his own, his power of action will thereby be

aided and fostered, whereas, if he be thrown among such as are but very

little in harmony with his nature, he will hardly be able to accommodate

himself to them without undergoing a great change himself. VIII. Whatsoever in

nature we deem to be evil, or to be capable of injuring our faculty for

existing and enjoying the rational life, we may endeavour to remove in

whatever way seems safest to us; on the other hand, whatsoever we deem to

be good or useful for preserving our being, and enabling us to enjoy the

rational life, we may appropriate to our use and employ as we think best.

Everyone without exception may, by sovereign right of nature, do

whatsoever he thinks will advance his own interest. IX. Nothing can be in

more harmony with the nature of any given thing than other individuals of

the same species; therefore (cf.

vii.) for man in

the preservation of his being and the enjoyment of the rational life there

is nothing more useful than his fellow-man who is led by reason. Further,

as we know not anything among individual things which is more excellent

than a man led by reason, no man can better display the power of his skill

and disposition, than in so training men, that they come at last to live

under the dominion of their own reason. X. In

so far as men are influenced by envy or any kind of hatred, one towards

another, they are at variance, and are therefore to be feared in

proportion, as they are more powerful than their fellows. XI. Yet minds are not

conquered by force, but by love and high-mindedness. XII. It is before all

things useful to men to associate their ways of life, to bind themselves

together with such bonds as they think most fitted to gather them all into

unity, and generally to do whatsoever serves to strengthen friendship. XIII. But for this

there is need of skill and watchfulness. For men are diverse (seeing that

those who live under the guidance of reason are few), yet are they are

generally envious and more prone to revenge than to sympathy. No small

force of character is therefore required to take everyone as he is, and to

restrain one's self from imitating the emotions of others. But those who

carp at mankind, and are more skilled in railing at vice than in

instilling virtue, and who break rather than strengthen men's

dispositions, are hurtful both to themselves and others. Thus many from

too great impatience of spirit, or from misguided religious zeal, have

preferred to live among brutes rather than among men; as boys or youths,

who cannot peaceably endure the chidings of their parents, will enlist as

soldiers and choose the hardships of war and the despotic discipline in

preference to the comforts of home and the admonitions of their father:

suffering any burden to be put upon them, so long as they may spite their

parents. XIV. Therefore, although men are generally governed in everything by their own lusts, yet their association in common brings many more advantages than drawbacks. Wherefore it is better to bear patiently the wrongs they may do us, and to strive to promote whatsoever serves to bring about harmony and friendship. XV. Those things, which beget harmony, are such as are attributable to justice, equity, and honourable living. For men brook ill not only what is unjust or iniquitous, but also what is reckoned disgraceful, or that a man should slight the received customs of their society. For winning love those qualities are especially necessary, which have regard to religion and piety (cf. IV. xxxvii. notes, i. ii.; xlvi. note; and lxxiii. note). XVI. Further, harmony is

often the result of fear: but such harmony is insecure. Further, fear

arises from infirmity of spirit, and moreover belongs not to the exercise

of reason: the same is true of compassion, though this latter seems to

bear a certain resemblance to piety. . . . XXVI. Besides

men, we know of no particular thing in nature in whose mind we may

rejoice, and whom we can associate with ourselves in friendship or any

sort of fellowship; therefore, whatsoever there be in nature besides man,

a regard for our advantage does not call on us to preserve, but to

preserve or destroy according to its various capabilities, and to adapt to

our use as best we may. XXVII. The advantage which we derive

from things external to us, besides the experience and knowledge which we

acquire from observing them, and from recombining their elements in

different forms, is principally the preservation of the body; from this

point of view, those things are most useful which can so feed and nourish

the body, that all its parts may rightly fulfil their functions. For, in

proportion as the body is capable of being affected in a greater variety

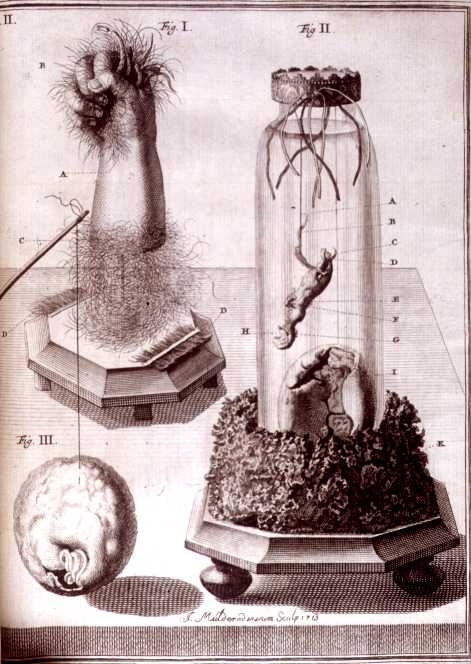

of ways, and of affecting external bodies in a great number of ways, so

much the more is the mind capable of thinking (IV.

xxxviii.

xxxix.). But there

seem to be very few things of this kind in nature; wherefore for the due

nourishment of the body we must use many foods of diverse nature. For the

human body is composed of very many parts of different nature, which stand

in continual need of varied nourishment, so that the whole body may be

equally capable of doing everything that can follow from its own nature,

and consequently that the mind also may be equally capable of forming many

perceptions. XXVIII. Now for providing these

nourishments the strength of each individual would hardly suffice, if men

did not lend one another mutual aid. But money has furnished us with a

token for everything: hence it is with the notion of money, that the mind

of the multitude is chiefly engrossed: nay, it can hardly conceive any

kind of pleasure, which is not accompanied with the idea of money as

cause. XXIX. This

result is the fault only of those, who seek money, not from poverty or to

supply their necessary wants, but because they have learned the arts of

gain, wherewith they bring themselves to great splendour. Certainly they

nourish their bodies, according to custom, but scantily, believing that

they lose as much of their wealth as they spend on the preservation of

their body. But they who know the true use of money, and who fix the

measure of wealth solely with regard to their actual needs live content

with little. XXX. As,

therefore, those things are good which assist the various parts of the

body, and enable them to perform their functions; and as pleasure consists

in an increase of, or aid to, man's power, in so far as he is composed of

mind and body; it follows that all those things which bring pleasure are

good. But seeing that things do not work with the object of giving us

pleasure, and that their power of action is not tempered to suit our

advantage, and, lastly, that pleasure is generally referred to one part of

the body more than to the other parts; therefore most emotions of pleasure

(unless reason and watchfulness be at hand), and consequently the desires

arising therefrom, may become excessive. Moreover we may add that emotion

leads us to pay most regard to what is agreeable in the present, nor can

we estimate what is future with emotions equally vivid. (IV.

xliv. note, and

lx. note.) XXXI. Superstition, on the other hand, seems to account as good all that brings pain, and as bad all that brings pleasure. However, as we said above (IV. xlv. note), none but the envious take delight in my infirmity and trouble. For the greater the pleasure whereby we are affected, the greater is the perfection whereto we pass, and consequently the more do we partake of the divine nature: no pleasure can ever be evil, which is regulated by a true regard for our advantage. But contrariwise he, who is led by fear and does good only to avoid evil, is not guided by reason. XXXII. But human

power is extremely limited, and is infinitely surpassed by the power of

external causes; we have not, therefore, an absolute power of shaping to

our use those things which are without us. Nevertheless, we shall bear

with an equal mind all that happens to us in contravention to the claims

of our own advantage, so long as we are conscious, that we have done our

duty, and that the power which we possess is not sufficient to enable us

to protect ourselves completely; remembering that we are a part of

universal nature, and that we follow her order. If we have a clear and

distinct understanding of this, that part of our nature which is defined

by intelligence, in other words the better part of ourselves, will

assuredly acquiesce in what befalls us, and in such acquiescence will

endeavour to persist. For, in so far as we are intelligent beings, we

cannot desire anything save that which is necessary, nor yield absolute

acquiescence to anything, save to that which is true: wherefore, in so far

as we have a right understanding of these things, the endeavour of the

better part of ourselves is in harmony with the order of nature as a

whole. |

Bliss, Beatitude, Acquiescence

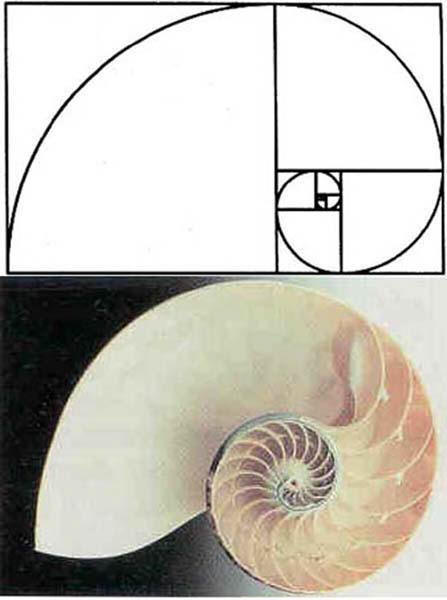

PROP. XXVII. From this third kind of knowledge arises the highest possible mental acquiescence.

Proof.--The highest virtue of the mind is to know God (IV. xxviii.), or to understand things by the third kind of knowledge (V. xxv.), and this virtue is greater in proportion as the mind knows things more by the said kind of knowledge (V. xxiv.): consequently, he who knows things by this kind of knowledge passes to the summit of human perfection, and is therefore (Def. of the Emotions, ii.) affected by the highest pleasure, such pleasure being accompanied by the idea of himself and his own virtue; thus (Def. of the Emotions, xxv.), from this kind of knowledge arises the highest possible acquiescence. Q.E.D.

\\

\\

Beatitude is not the reward of virtue, it is virtue itself.

PROP. XXXVI. The intellectual love of the mind towards God is that very love of God whereby God loves himself, not in so far as he is infinite, but in so far as he can be explained through the essence of the human mind regarded under the form of eternity; in other words, the intellectual love of the mind towards God is part of the infinite love wherewith God loves himself.