Chapter 9

Other Questions Concerning the Same Books: Namely Whether They Were Completely Finished by Ezra, and, Further, Whether the Marginal Notes Which Are Found in the Hebrew Texts Were Various Readings

How greatly the inquiry we have just made concerning the real writer of

the twelve books aids us in attaining a complete understanding of them, may be

easily gathered solely from the passages which we have adduced in confirmation

of our opinion, and which would be most obscure without it. But besides the

question of the writer, there are other points to notice which common superstition forbids the multitude to apprehend. Of

these the chief is, that Ezra (whom I will take to be the author of the

aforesaid books until some more likely person be suggested) did not put the

finishing touches to the narrative contained therein, but merely collected the

histories from various writers, and sometimes simply set them down, leaving

their examination and arrangement to posterity.

The cause (if it were not untimely death) which

prevented him from completing his work in all its portions, I cannot conjecture,

but the fact remains most clear, although we have lost the writings of the

ancient Hebrew historians, and can only judge from the few fragments which are

still extant. For the history of Hezekiah (2 Kings xviii:17), as written in the

vision of Isaiah, is related as it is found in the chronicles of the kings of

Judah. We read the same story, told with few exceptions, [N11], in the same

words, in the book of Isaiah which was contained in the chronicles of the kings

of Judah (2 Chron. xxxii:32). From this we must conclude that there were various

versions of this narrative of Isaiah's, unless, indeed, anyone would dream that

in this, too, there lurks a mystery. Further, the last chapter of 2 Kings 27-30

is repeated in the last chapter of Jeremiah, v.31-34.

Again, we find 2 Sam. vii. repeated in I Chron. xvii., but the expressions in the two passages are so curiously varied [N12], that we can very easily see that these two chapters were taken from two different versions of the history of Nathan.

Lastly, the genealogy of the kings of Idumaea

contained in Genesis xxxvi:31, is repeated in the same words in 1 Chron. i.,

though we know that the author of the latter work took his materials from other

historians, not from the twelve books we have ascribed to Ezra. We may therefore

be sure that if we still possessed the writings of the historians, the matter

would be made clear; however, as we have lost them, we can only examine the

writings still extant, and from their order and connection, their various

repetitions, and, lastly, the contradictions in dates which they contain, judge

of the rest.

These, then, or the chief of them, we will now go through. First, in the story of Judah and Tamar (Gen. xxxviii.) the historian thus begins: "And it came to pass at that time that Judah went down from his brethren." This time cannot refer to what immediately precedes [N13], but must necessarily refer to something else, for from the time when Joseph was sold into Egypt to the time when the patriarch Jacob, with all his family, set out thither, cannot be reckoned as more than twenty-two years, for Joseph, when he was sold by his brethren, was seventeen years old, and when he was summoned by Pharaoh from prison was thirty; if to this we add the seven years of plenty and two of famine, the total amounts to twenty-two years. Now, in so short a period, no one can suppose that so many things happened as are described; that Judah had three children, one after the other, from one wife, whom he married at the beginning of the period; that the eldest of these, when he was old enough, married Tamar, and that after he died his next brother succeeded to her; that, after all this, Judah, without knowing it, had intercourse with his daughter-in-law, and that she bore him twins, and, finally, that the eldest of these twins became a father within the aforesaid period. As all these events cannot have taken place within the period mentioned in Genesis, the reference must necessarily be to something treated of in another book: and Ezra in this instance simply related the story, and inserted it without examination among his other writings.

However, not only this chapter but the whole

narrative of Joseph and Jacob is collected and set forth from various histories,

inasmuch as it is quite inconsistent with itself. For in Gen. xlvii. we are told

that Jacob, when he came at Joseph's bidding to salute Pharaoh, was 130 years

old. If from this we deduct the twenty-two years which he passed sorrowing for

the absence of Joseph and the seventeen years forming Joseph's age when he was

sold, and, lastly, the seven years for which Jacob served for Rachel, we find

that he was very advanced in life, namely, eighty four, when he took Leah to

wife, whereas Dinah was scarcely seven years old when she was violated by

Shechem, [N14]. Simeon and Levi were aged respectively eleven and twelve when

they spoiled the city and slew all the males therein with the sword.

There is no need that I should go through the

whole Pentateuch. If anyone pays attention to the way in which all the histories

and precepts in these five books are set down promiscuously and without order,

with no regard for dates; and further, how the same story is often repeated,

sometimes in a different version, he will easily, I say, discern that all the

materials were promiscuously collected and heaped together, in order that they

might at some subsequent time be more readily examined and reduced to order. Not

only these five books, but also the narratives contained in the remaining seven,

going down to the destruction of the city, are compiled in the same way. For who

does not see that in Judges ii:6 a new historian is being quoted, who had also

written of the deeds of Joshua, and that his words are simply copied? For after

our historian has stated in the last chapter of the book of Joshua that Joshua

died and was buried, and has promised, in the first chapter of Judges, to relate

what happened after his death, in what way, if he wished to continue the thread

of his history, could he connect the statement here made about Joshua with what

had gone before?

So, too, 1 Sam. 17, 18, are taken from another

historian, who assigns a cause for David's first frequenting Saul's court very

different from that given in chap. xvi. of the same book. For he did not think

that David came to Saul in consequence of the advice of Saul's servants, as is

narrated in chap. xvi., but that being sent by chance to the camp by his father

on a message to his brothers, he was for the first time remarked by Saul on the

occasion of his victory, over Goliath the Philistine, and was retained at his

court.

I suspect the same thing has taken place in chap.

xxvi. of the same book, for the historian there seems to repeat the narrative

given in chap. xxiv. according to another man's version. But I pass over this,

and go on to the computation of dates.

In I Kings, chap. vi., it is said that Solomon built the Temple in the four hundred and eightieth year after the exodus from Egypt; but from the historians themselves we get a much longer period, for:

Moses governed the people in the desert . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Joshua, who lived 110 years, did not, according to

Josephus and others' opinion rule more than . . . . . . . . . 26

Cusban Rishathaim held the people in subjection . . . . . . . . . 8

Othniel, son of Kenag, was judge for . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40 [N15]

Eglon, King of Moab, governed the people . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Ehucl and Shamgar were judges . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

Jachin, King of Canaan, held the people in subjection . . . . . . 20

The people was at peace subsequently for . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

It was under subjection to Median . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

It obtained freedom under Gideon for . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

It fell under the rule of Abimelech . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Tola, son of Puah, was judge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Jair was judge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

The people was in subjection to the Philistines and Ammonites . . 18

Jephthah was judge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Ibzan, the Bethlehemite, was judge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Elon, the Zabulonite . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Abclon, the Pirathonite . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

The people was again subject to the Philistines . . . . . . . . . 40

Samson was judge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20 [N16]

Eli was judge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

The people again fell into subjection to the Philistines,

till they were delivered by Samuel . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

David reigned . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Solomon reigned before he built the temple . . . . . . . . . . . 4

All these periods added

together make a total of 580 years. But to these must be added the years

during which the Hebrew republic flourished after the death of Joshua,

until it was conquered by Cushan Rishathaim, which I take to be very

numerous, for I cannot bring myself to believe that immediately after

the death of Joshua all those who had witnessed his miracles died simultaneously,

nor that their successors at one stroke bid farewell to their laws, and

plunged from the highest virtue into the depth of wickedness and

obstinacy.

Nor, lastly, that Cushan Rishathaim subdued them on

the instant; each one of these circumstances requires almost a generation, and

there is no doubt that Judges ii:7, 9, 10, comprehends a great many years which

it passes over in silence. We must also add the years during which Samuel was

judge, the number of which is not stated in Scripture, and also the years during

which Saul reigned, which are not clearly shown from his history. It is, indeed,

stated in 1 Sam. xiii:1, that he reigned two years, but the text in that passage

is mutilated, and the records of his reign lead us to suppose a longer period.

That the text is mutilated I suppose no one will doubt who has ever advanced so

far as the threshold of the Hebrew language, for it runs as follows: "Saul was

in his -- year, when he began to reign, and he reigned two years over Israel."

Who, I say, does not see that the number of the years of Saul's age when he

began to reign has been omitted? That the record of the reign presupposes a

greater number of years is equally beyond doubt, for in the same book, chap.

xxvii:7, it is stated that David sojourned among the Philistines, to whom he had

fled on account of Saul, a year and four months; thus the rest of the reign must

have been comprised in a space of eight months, which I think no one will

credit. Josephus, at the end of the sixth book of his antiquities, thus corrects

the text: Saul reigned eighteen years while Samuel was alive, and two years

after his death. However, all the narrative in chap. xiii. is in complete

disagreement with what goes before. At the end of chap. vii. it is narrated that

the Philistines were so crushed by the Hebrews that they did not venture, during

Samuel's life, to invade the borders of Israel; but in chap. xiii. we are told

that the Hebrews were invaded during the life of Samuel by the Philistines, and

reduced by them to such a state of wretchedness and poverty that they were

deprived not only of weapons with which to defend themselves, but also of the

means of making more. I should be at pains enough if I were to try and harmonize

all the narratives contained in this first book of Samuel so that they should

seem to be all written and arranged by a single historian. But I return to my

object. The years, then, during which Saul reigned must be added to the above

computation; and, lastly, I have not counted the years of the Hebrew anarchy,

for I cannot from Scripture gather their number. I cannot, I say, be certain as

to the period occupied by the events related in Judges chap. xvii. on till the

end of the book.

It is thus abundantly evident

that we cannot arrive at a true computation of years from the histories, and,

further, that the histories are inconsistent themselves on the subject. We are

compelled to confess that these histories were compiled from various writers

without previous arrangement and examination. Not less discrepancy is found

between the dates given in the Chronicles of the Kings of Judah, and those in

the Chronicles of the Kings of Israel; in the latter, it is stated that Jehoram,

the son of Ahab, began to reign in the second year of the reign of Jehoram, the

son of Jehoshaphat (2 Kings i:17), but in the former we read that Jehoram, the

son of Jehoshaphat, began to reign in the fifth year of Jehoram, the son of Ahab

(2 Kings viii:16). Anyone who compares the narratives in Chronicles with the

narratives in the books of Kings, will find many similar discrepancies. These

there is no need for me to examine here, and still less am I called upon to

treat of the commentaries of those who endeavour to harmonize them. The Rabbis

evidently let their fancy run wild. Such commentators as I have, read, dream,

invent, and as a last resort, play fast and loose with the language. For

instance, when it is said in 2 Chronicles, that Ahab was forty-two years old

when he began to reign, they pretend that these years are computed from the

reign of Omri, not from the birth of Ahab. If this can be shown to be the real

meaning of the writer of the book of Chronicles, all I can say is, that he did

not know how to state a fact. The commentators make many other assertions of

this kind, which if true, would prove that the ancient Hebrews were ignorant

both of their own language, and of the way to relate a plain narrative. I should

in such case recognize no rule or reason in interpreting Scripture, but it would

be permissible to hypothesize to one's heart's content.

If anyone thinks that I am speaking too generally, and without sufficient warrant, I would ask him to set himself to showing us some fixed plan in these histories which might be followed without blame by other writers of chronicles, and in his efforts at harmonizing and interpretation, so strictly to observe and explain the phrases and expressions, the order and the connections, that we may be able to imitate these also in our writings, [N17]. If he succeeds, I will at once give him my hand, and he shall be to me as great Apollo; for I confess that after long endeavours I have been unable to discover anything of the kind. I may add that I set down nothing here which I have not long reflected upon, and that, though I was imbued from my boyhood up with the ordinary opinions about the Scriptures, I have been unable to withstand the force of what I have urged.

However, there is no need

to detain the reader with this question, and drive him to attempt an impossible

task; I merely mentioned the fact in order to throw light on my intention.

I now pass on to other points concerning the treatment

of these books. For we must remark, in addition to what has been shown, that

these books were not guarded by posterity with such care that no faults crept

in. The ancient scribes draw attention to many doubtful readings, and some

mutilated passages, but not to all that exist: whether the faults are of

sufficient importance to greatly embarrass the reader I will not now discuss. I

am inclined to think that they are of minor moment to those, at any rate, who

read the Scriptures with enlightenment: and I can positively affirm that I have

not noticed any fault or various reading in doctrinal passages sufficient to

render them obscure or doubtful.

There are some people, however, who will not admit

that there is any corruption, even in other passages, but maintain that by some

unique exercise of providence God has preserved from corruption every word in

the Bible: they say that the various readings are the symbols of profoundest

mysteries, and that mighty secrets lie hid in the twenty-eight hiatus which

occur, nay, even in the very form of the letters.

Whether they are actuated by folly and anile devotion,

or whether by arrogance and malice so that they alone may be held to possess the

secrets of God, I know not: this much I do know, that I find in their writings

nothing which has the air of a Divine secret, but only childish lucubrations. I

have read and known certain Kabbalistic triflers, whose insanity provokes my

unceasing astonishment. That faults have crept in will, I think, be denied by no

sensible person who reads the passage about Saul, above quoted (1 Sam. xiii:1)

and also 2 Sam. vi:2: "And David arose and went with all the people that were

with him from Judah, to bring up from thence the ark of God."

No one can fail to remark that the name of their destination, viz., Kirjath-jearim [N18], has been omitted: nor can we deny that 2 Sam. xiii:37, has been tampered with and mutilated. "And Absalom fled, and went to Talmai, the son of Ammihud, king of Geshur. And he mourned for his son every day. So Absalom fled, and went to Geshur, and was there three years." I know that I have remarked other passages of the same kind, but I cannot recall them at the moment.

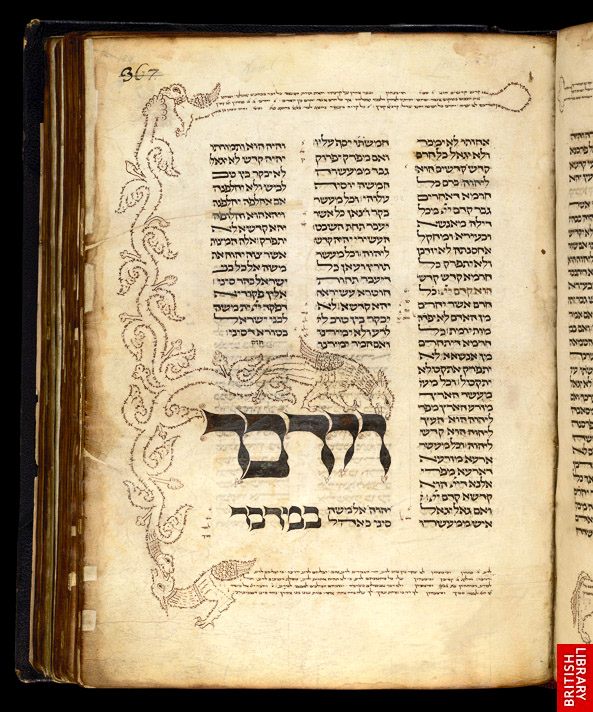

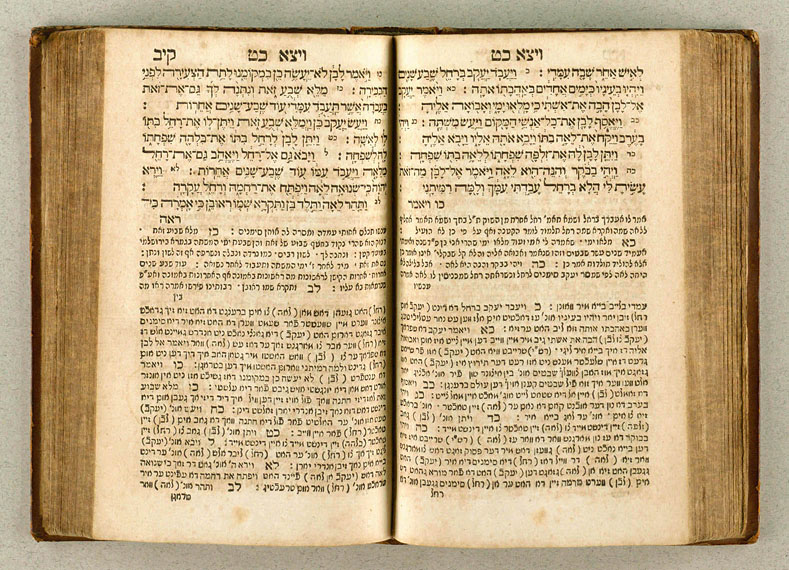

That the marginal notes which are found

continually in the Hebrew Codices are doubtful readings will, I think, be

evident to everyone who has noticed that they often arise from the great

similarity, of some of the Hebrew letters, such for instance, as the similarity

between Kaph and Beth, Jod and Van, Daleth and Reth, &c. For example, the

text in 2 Sam. v:24, runs "in the time when thou hearest," and similarly in

Judges xxi:22, "And it shall be when their fathers or their brothers come unto

us often," the marginal version is "come unto us to complain."

So also many various readings have arisen from the use

of the letters named mutes, which are generally not sounded in pronunciation,

and are taken promiscuously, one for the other. For example, in Levit. xxv:29,

it is written, "The house shall be established which is not in the walled city,"

but the margin has it, "which is in a walled city."

Though these matters are self-evident, it is

necessary, to answer the reasonings of certain Pharisees, by which they

endeavour to convince us that the marginal notes serve to indicate some mystery,

and were added or pointed out by the writers of the sacred books. The first of

these reasons, which, in my, opinion, carries little weight, is taken from the

practice of reading the Scriptures aloud.

If, it is urged, these notes were added to show

various readings which could not be decided upon by posterity, why has custom

prevailed that the marginal readings should always be retained? Why has the

meaning which is preferred been set down in the margin when it ought to have

been incorporated in the text, and not relegated to a side note?

The second reason is more specious, and is taken from

the nature of the case. It is admitted that faults have crept into the sacred

writings by chance and not by design; but they say that in the five books the

word for a girl is, with one exception, written without the letter "he,"

contrary to all grammatical rules, whereas in the margin it is written correctly

according to the universal rule of grammar. Can this have happened by mistake?

Is it possible to imagine a clerical error to have been committed every, time

the word occurs? Moreover, it would have been easy, to supply the emendation.

Hence, when these readings are not accidental or corrections of manifest

mistakes, it is supposed that they must have been set down on purpose by the

original writers, and have a meaning. However, it is easy to answer such

arguments; as to the question of custom having prevailed in the reading of the

marginal versions, I will not spare much time for its consideration: I know not

the promptings of superstition, and perhaps the practice may have arisen

from the idea that both readings were deemed equally good or tolerable, and

therefore, lest either should be neglected, one was appointed to be written, and

the other to be read. They feared to pronounce judgment in so weighty a matter

lest they should mistake the false for the true, and therefore they would give

preference to neither, as they must necessarily have done if they had commanded

one only to be both read and written. This would be especially the case where

the marginal readings were not written down in the sacred books: or the custom

may have originated because some things though rightly written down were desired

to be read otherwise according to the marginal version, and therefore the

general rule was made that the marginal version should be followed in reading

the Scriptures. The cause which induced the scribes to expressly prescribe

certain passages to be read in the marginal version, I will now touch on, for

not all the marginal notes are various readings, but some mark expressions which

have passed out of common use, obsolete words and terms which current decency

did not allow to be read in a public assembly. The ancient writers, without any

evil intention, employed no courtly paraphrase, but called things by their plain

names. Afterwards, through the spread of evil thoughts and luxury, words which

could be used by the ancients without offence, came to be considered obscene.

There was no need for this cause to change the text of Scripture. Still, as a

concession to the popular weakness, it became the custom to substitute more

decent terms for words denoting sexual intercourse, exereta, &c., and to

read them as they were given in the margin.

At any rate, whatever may have been the origin of the

practice of reading Scripture according to the marginal version, it was not that

the true interpretation is contained therein. For besides that, the Rabbins in

the Talmud often differ from the Massoretes, and give other readings which they

approve of, as I will shortly show, certain things are found in the margin which

appear less warranted by the uses of the Hebrew language. For example, in 2

Samuel xiv:22, we read, "In that the king hath fulfilled the request of his

servant," a construction plainly regular, and agreeing with that in chap. xvi.

But the margin has it "of thy servant," which does not agree with the person of

the verb. So, too, chap. xvi:25 of the same book, we find, "As if one had

inquired at the oracle of God," the margin adding "someone" to stand as a

nominative to the verb. But the correction is not apparently warranted, for it

is a common practice, well known to grammarians in the Hebrew language, to use

the third person singular of the active verb impersonally.

The second argument advanced by the Pharisees is

easily answered from what has just been said, namely, that the scribes besides

the various readings called attention to obsolete words. For there is no doubt

that in Hebrew as in other languages, changes of use made many words obsolete

and antiquated, and such were found by the later scribes in the sacred books and

noted by them with a view to the books being publicly read according to custom.

For this reason the word nahgar is always found marked because its gender was

originally common, and it had the same meaning as the Latin juvenis (a young

person). So also the Hebrew capital was anciently called Jerusalem, not

Jerusalaim. As to the pronouns himself and herself, I think that the later

scribes changed vau into jod (a very frequent change in Hebrew) when they wished

to express the feminine gender, but that the ancients only distinguished the two

genders by a change of vowels. I may also remark that the irregular tenses of

certain verbs differ in the ancient and modern forms, it being formerly

considered a mark of elegance to employ certain letters agreeable to the ear.

In a word, I could easily multiply proofs of this kind

if I were not afraid of abusing the patience of the reader. Perhaps I shall be

asked how I became acquainted with the fact that all these expressions are

obsolete. I reply that I have found them in the most ancient Hebrew writers in

the Bible itself, and that they have not been imitated by subsequent authors,

and thus they are recognized as antiquated, though the language in which they

occur is dead. But perhaps someone may press the question why, if it be true, as

I say, that the marginal notes of the Bible generally mark various readings,

there are never more than two readings of a passage, that in the text and that

in the margin, instead of three or more; and further, how the scribes can have

hesitated between two readings, one of which is evidently contrary to grammar,

and the other a plain correction.

The answer to

these questions also is easy: I will premise that it is almost certain that

there once were more various readings than those now recorded. For instance, one

finds many in the Talmud which the Massoretes have neglected, and are so

different one from the other that even the superstitious editor of the Bomberg Bible confesses

that he cannot harmonize them. "We cannot say anything," he writes, "except what

we have said above, namely, that the Talmud is generally in contradiction to the

Massorete." So that we are nor bound to hold that there never were more than two

readings of any passage, yet I am willing to admit, and indeed I believe that

more than two readings are never found: and for the following reasons:- (I.) The

cause of the differences of reading only admits of two, being generally the

similarity of certain letters, so that the question resolved itself into which

should be written Beth, or Kaf, Jod or Vau, Daleth or Reth: cases which are

constantly occurring, and frequently yielding a fairly good meaning whichever

alternative be adopted. Sometimes, too, it is a question whether a syllable be

long or short, quantity being determined by the letters called mutes. Moreover,

we never asserted that all the marginal versions, without exception, marked

various readings; on the contrary, we have stated that many were due to motives

of decency or a desire to explain obsolete words. (II.) I am inclined to

attribute the fact that more than two readings are never found to the paucity of

exemplars, perhaps not more than two or three, found by the scribes. In the

treatise of the scribes, chap. vi., mention is made of three only, pretended to

have been found in the time of Ezra, in order that the marginal versions might

be attributed to him.

However that may be, if the scribes only had three

codices we may easily imagine that in a given passage two of them would be in

accord, for it would be extraordinary if each one of the three gave a different

reading of the same text.

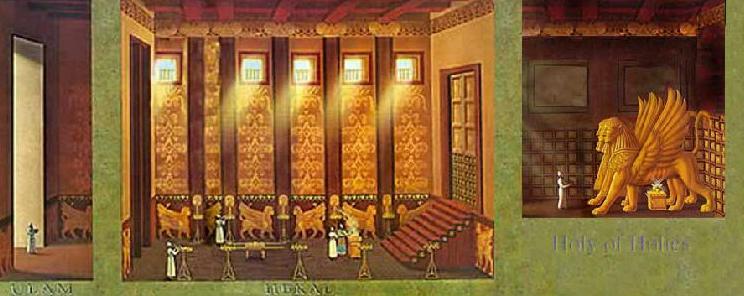

The dearth of copies after the time of Ezra will

surprise no one who has read the 1st chapter of Maccabees, or Josephus's

"Antiquities," Bk. 12, chap. 5. Nay, it appears wonderful considering the fierce

and daily persecution, that even these few should have been preserved. This

will, I think, be plain to even a cursory reader of the history of those times.

We have thus discovered the reasons why there are

never more than two readings of a passage in the Bible, but this is a long way

from supposing that we may therefore conclude that the Bible was purposely

written incorrectly in such passages in order to signify some mystery. As to the

second argument, that some passages are so faultily written that they are at

plain variance with all grammar, and should have been corrected in the text and

not in the margin, I attach little weight to it, for I am not concerned to say

what religious motive the scribes may have had for acting as they did: possibly

they did so from candour, wishing to transmit the few exemplars of the Bible

which they had found exactly in their original state, marking the differences

they discovered in the margin, not as doubtful readings, but as simple variants.

I have myself called them doubtful readings, because it would be generally

impossible to say which of the two versions is preferable.

Lastly, besides these doubtful readings the scribes

have (by leaving a hiatus in the middle of a paragraph) marked several passages

as mutilated. The Massoretes have counted up such instances, and they amount to

eight-and-twenty. I do not know whether any mystery is thought to lurk in the

number, at any rate the Pharisees religiously preserve a certain amount of empty

space.

One of such hiatus occurs (to give an instance) in

Gen. iv:8, where it is written, "And Cain said to his brother .... and it came

to pass while they were in the field, &c.," a space being left in which we

should expect to hear what it was that Cain said.

Similarly there are (besides those points we have noticed) eight-and- twenty hiatus left by the scribes. Many of these would not be recognized as mutilated if it were not for the empty space left. But I have said enough on this subject.

[Note N11]: "With few exceptions." One of these exceptions is found in 2 Kings xviii:20, where we read, "Thou sayest (but they are but vain words), "the second person being used. In Isaiah xxxvi:5, we read "I say (but they are but vain words) I have counsel and strength for war," and in the twenty-second verse of the chapter in Kings it is written, "But if ye say," the plural number being used, whereas Isaiah gives the singular. The text in Isaiah does not contain the words found in 2 Kings xxxii:32. Thus there are several cases of various readings where it is impossible to distinguish the best.

[Note N12]: "The expressions in the two passages are so varied." For

instance we read in 2 Sam. vii:6, "But I have walked in a tent and in a

tabernacle." Whereas in 1 Chron. xvii:5, "but have gone from tent to tent and

from one tabernacle to another." In 2 Sam. vii:10, we read, "to afflict

them,"whereas in 1 Chron. vii:9, we find a different expression. I could point

out other differences still greater, but a single reading of the chapters in

question will suffice to make them manifest to all who are neither blind nor

devoid of sense.

[Note N13]: "This time cannot refer to what immediately precedes." It is

plain from the context that this passage must allude to the time when Joseph was

sold by his brethren. But this is not all. We may draw the same conclusion from

the age of Judah, who was than twenty-two years old at most, taking as basis of

calculation his own history just narrated. It follows, indeed, from the last

verse of Gen. xxx., that Judah was born in the tenth of the years of Jacob's

servitude to Laban, and Joseph in the fourteenth. Now, as we know that Joseph

was seventeen years old when sold by his brethren, Judah was then not more than

twenty-one. Hence, those writers who assert that Judah's long absence from his

father's house took place before Joseph was sold, only seek to delude themselves

and to call in question the Scriptural authority which they are anxious to

protect.

[Note N14]: "Dinah was scarcely seven years old when she was violated by Schechem." The opinion held by some that Jacob wandered about eight or ten years between Mesopotamia and Bethel, savours of the ridiculous; if respect for Aben Ezra, allows me to say so. For it is clear that Jacob had two reasons for haste: first, the desire to see his old parents; secondly, and chiefly to perform, the vow made when he fled from his brother (Gen. xxviii:10 and xxxi:13, and xxxv:1). We read (Gen. xxxi:3), that God had commanded him to fulfill his vow, and promised him help for returning to his country. If these considerations seem conjectures rather than reasons, I will waive the point and admit that Jacob, more unfortunate than Ulysses, spent eight or ten years or even longer, in this short journey. At any rate it cannot be denied that Benjamin was born in the last year of this wandering, that is by the reckoning of the objectors, when Joseph was sixteen or seventeen years old, for Jacob left Laban seven years after Joseph's birth. Now from the seventeenth year of Joseph's age till the patriarch went into Egypt, not more than twenty-two years elapsed, as we have shown in this chapter. Consequently Benjamin, at the time of the journey to Egypt, was twenty-three or twenty- four at the most. He would therefore have been a grandfather in the flower of his age (Gen. xlvi:21, cf. Numb. xxvi:38, 40, and 1 Chron. viii;1), for it is certain that Bela, Benjamin's eldest son, had at that time, two sons, Addai and Naaman. This is just as absurd as the statement that Dinah was violated at the age of seven, not to mention other impossibilities which would result from the truth of the narrative. Thus we see that unskillful endeavours to solve difficulties, only raise fresh ones, and make confusion worse confounded.

[Note N15]: "Othniel, son of Kenag, was judge for forty years." Rabbi Levi Ben Gerson and others believe that these forty years which the Bible says were passed in freedom, should be counted from the death of Joshua, and consequently include the eight years during which the people were subject to Kushan Rishathaim, while the following eighteen years must be added on to the eighty years of Ehud's and Shamgar's judgeships. In this case it would be necessary to reckon the other years of subjection among those said by the Bible to have been passed in freedom. But the Bible expressly notes the number of years of subjection, and the number of years of freedom, and further declares (Judges ii:18) that the Hebrew state was prosperous during the whole time of the judges. Therefore it is evident that Levi Ben Gerson (certainly a very learned man), and those who follow him, correct rather than interpret the Scriptures. The same fault is committed by those who assert, that Scripture, by this general calculation of years, only intended to mark the period of the regular administration of the Hebrew state, leaving out the years of anarchy and subjection as periods of misfortune and interregnum. Scripture certainly passes over in silence periods of anarchy, but does not, as they dream, refuse to reckon them or wipe them out of the country's annals. It is clear that Ezra, in 1 Kings vi., wished to reckon absolutely all the years since the flight from Egypt. This is so plain, that no one versed in the Scriptures can doubt it. For, without going back to the precise words of the text, we may see that the genealogy of David given at the end of the book of Ruth, and I Chron. ii., scarcely accounts for so great a number of years. For Nahshon, who was prince of the tribe of Judah (Numb. vii;11), two years after the Exodus, died in the desert, and his son Salmon passed the Jordan with Joshua. Now this Salmon, according to the genealogy, was David's great-grandfather. Deducting, then, from the total of 480 years, four years for Solomon's reign, seventy for David's life, and forty for the time passed in the desert, we find that David was born 366 years after the passage of the Jordan. Hence we must believe that David's father, grandfather, great-grandfather, and great- great-grandfather begat children when they were ninety years old.

[Note N16]: "Samson was judge for twenty years." Samson was born after the Hebrews had fallen under the dominion of the Philistines.

[Note N17]: Otherwise, they rather correct than explain Scripture.

[Note N18]: "Kirjath-jearim." Kirjath-jearim is also called Baale of

Judah. Hence Kimchi and others think that the words Baale Judah, which I have

translated "the people of Judah," are the name of a town. But this is not so,

for the word Baale is in the plural. Moreover, comparing this text in Samuel

with I Chron. Xiii:5, we find that David did not rise up and go forth out of

Baale, but that he went thither. If the author of the book of Samuel had meant

to name the place whence David took the ark, he would, if he spoke Hebrew

correctly, have said, "David rose up, and set forth from Baale Judah, and took

the ark from thence."