Chapter 4

Of the Divine Law

The word law, taken in the abstract, means that by which an individual, or all

things, or as many things as belong to a particular species, act in one and the

same fixed and definite manner, which manner depends either on natural necessity

or on human decree. A law which depends on natural necessity is one which

necessarily follows from the nature, or from the definition of the thing in

question; a law which depends on human decree, and which is more

correctly called an ordinance, is one which men have laid down for themselves

and others in order to live more safely or conveniently, or from some similar

reason.

For example, the law that all bodies impinging on lesser bodies, lose as

much of their own motion as they communicate to the latter is a universal law of all bodies, and depends on natural

necessity. So, too, the law that a man in remembering one thing, straightway

remembers another either like it, or which he had perceived simultaneously with

it, is a law which necessarily follows from the nature of man. But the law that men must yield, or be compelled to yield,

somewhat of their natural right, and that they bind themselves to live in

a certain way, depends on human decree. Now, though I freely admit that all

things are predetermined by universal natural laws to exist and operate in a given, fixed, and

definite manner, I still assert that the laws I have just mentioned depend on human decree.

(1.) Because man, in so far as he is a part of nature,

constitutes a part of the power of nature. Whatever, therefore, follows

necessarily from the necessity of human nature (that is, from nature herself, in

so far as we conceive of her as acting through man) follows, even though it be

necessarily, from human power. Hence the sanction of such laws may very well be said to depend on man's decree,

for it principally depends on the power of the human mind; so that the human mind in respect to its perception of things as

true and false, can readily be conceived as without such laws, but not without

necessary law as we have just defined it.

(2.) I have stated that these laws depend on human decree because it is well to

define and explain things by their proximate causes. The general consideration

of fate and the concatenation of causes would aid us very little in forming and

arranging our ideas concerning particular questions. Let us add that as to the

actual coordination and concatenation of things, that is how things are ordained

and linked together, we are obviously ignorant; therefore, it is more profitable

for right living, nay, it is necessary for us to consider things as contingent. So much about law in the abstract.

Now the word law seems to be only applied to natural phenomena by

analogy, and is commonly taken to signify a command which men can either obey or

neglect, inasmuch as it restrains human nature within certain originally

exceeded limits, and therefore lays down no rule beyond human strength. Thus it

is expedient to define law more particularly as a plan of life laid down by

man for himself or others with a certain object.

However, as the true object of legislation is only

perceived by a few, and most men are almost incapable of grasping it, though

they live under its conditions, legislators, with a view to exacting general

obedience, have wisely put forward another object, very different from that

which necessarily follows from the nature of law: they promise to the observers

of the law that which the masses chiefly desire, and threaten its violators with

that which they chiefly fear: thus endeavouring to restrain the masses, as far

as may be, like a horse with a curb; whence it follows that the word law is chiefly applied to the modes of life enjoined on

men by the sway of others; hence those who obey the law are said to live under

it and to be under compulsion. In truth, a man who renders everyone their due

because he fears the gallows, acts under the sway and compulsion of others, and

cannot be called just. But a man who does the same from a knowledge of the true

reason for laws and their necessity, acts from a firm purpose and of his own

accord, and is therefore properly called just. This, I take it, is Paul's

meaning when he says, that those who live under the law cannot be justified through the law, for justice,

as commonly defined, is the constant and perpetual will to render every man his

due. Thus Solomon says (Prov. xxi:15), "It is a joy to the just

to do judgment," but the wicked fear.

Law, then, being a plan of living which men have for a

certain object laid down for themselves or others, may, as it seems, be divided

into human law and Divine law.

By human law I mean a plan of living which serves only to

render life and the state secure.

By Divine law I mean that which only regards the highest good, in other words, the true knowledge of God

and love.

I call this law Divine because of the nature of the highest good, which I will here shortly explain as

clearly as I can.

Inasmuch as the intellect is the best part of our being, it is evident

that we should make every effort to perfect it as far as possible if we desire

to search for what is really profitable to us. For in intellectual perfection the highest good should consist. Now, since all our

knowledge, and the certainty which removes every doubt, depend solely on the

knowledge of God;- firstly, because without God nothing can exist or be

conceived; secondly, because so long as we have no clear and distinct idea of

God we may remain in universal doubt - it follows that our highest good and perfection also depend solely on the

knowledge of God. Further, since without God nothing can exist or be conceived,

it is evident that all natural phenomena involve and express the conception of

God as far as their essence and perfection extend, so that we have greater

and more perfect knowledge of God in proportion to our knowledge of natural

phenomena: conversely (since the knowledge of an effect through its cause is the

same thing as the knowledge of a particular property of a cause) the greater our

knowledge of natural phenomena, the more perfect is our knowledge of the essence of God (which is the cause of all things). So,

then, our highest good not only depends on the knowledge of God,

but wholly consists therein; and it further follows that man is perfect or the

reverse in proportion to the nature and perfection of the object of his special

desire; hence the most perfect and the chief sharer in the highest blessedness is he who prizes above all else, and takes

especial delight in, the intellectual knowledge of God, the most perfect Being.

Hither, then, our highest good and our highest blessedness aim - namely, to the knowledge and love of

God; therefore the means demanded by this aim of all human actions, that is, by

God in so far as the idea of him is in us, may be called the commands of God,

because they proceed, as it were, from God Himself, inasmuch as He exists in our

minds, and the plan of life which has regard to this aim may be fitly called the

law of God.

The nature of the means, and the plan of life which

this aim demands, how the foundations of the best states follow its lines, and how men's life is

conducted, are questions pertaining to general ethics. Here I only proceed to

treat of the Divine law in a particular application.

As the love of God is man's highest happiness and blessedness, and the ultimate end and aim of all human

actions, it follows that he alone lives by the Divine law who loves God not from fear of punishment,

or from love of any other object, such as sensual pleasure, fame, or the like;

but solely because he has knowledge of God, or is convinced that the knowledge

and love of God is the highest good. The sum and chief precept, then, of the

Divine law is to love God as the highest good, namely, as we have said, not from fear of

any pains and penalties, or from the love of any other object in which we desire

to take pleasure. The idea of God lays down the rule that God is our highest good - in other words, that the knowledge and

love of God is the ultimate aim to which all our actions should be directed. The

worldling cannot understand these things, they appear foolishness to him because

he has too meager a knowledge of God, and also because in this highest good he can discover nothing which he can

handle or eat, or which affects the fleshly appetites wherein he chiefly

delights, for it consists solely in thought and the pure reason. They, on the other hand, who know that they

possess no greater gift than intellect and sound reason, will doubtless accept what I have said without

question.

We have now explained that wherein the Divine law chiefly consists, and what are human laws, namely, all those which have a different

aim unless they have been ratified by revelation, for in this respect also things are

referred to God (as we have shown above) and in this sense the law of Moses, although it was not universal, but entirely

adapted to the disposition and particular preservation of a single people, may

yet be called a law of God or Divine law, inasmuch as we believe that it was ratified

by prophetic insight. If we consider the nature of natural Divine law as we have just explained it, we shall see:

I. That it is universal or common to all men, for we have deduced it

from universal human nature.

II. That it does not

depend on the truth of any historical narrative whatsoever, for inasmuch as this

natural Divine law is comprehended solely by the consideration

of human nature, it is plain that we can conceive it as existing as well in Adam

as in any other man, as well in a man living among his fellows, as in a man who

lives by himself.

The truth of a historical narrative, however assured,

cannot give us the knowledge nor consequently the love of God, for love of God

springs from knowledge of Him, and knowledge of Him should be derived from

general ideas, in themselves certain and known, so that the truth of a

historical narrative is very far from being a necessary requisite for our

attaining our highest good.

Still, though the truth of histories cannot give us

the knowledge and love of God, I do not deny that reading them is very useful

with a view to life in the world, for the more we have observed and known of

men's customs and circumstances, which are best revealed by their actions, the

more warily we shall be able to order our lives among them, and so far as reason dictates to adapt our actions to their

dispositions.

III. We see that this natural Divine law does not demand the performance of

ceremonies - that is, actions in themselves indifferent, which are called good

from the fact of their institution, or actions symbolizing something profitable

for salvation, or (if one prefers this definition) actions of which the meaning

surpasses human understanding. The natural light of reason does not demand anything which it is itself

unable to supply, but only such as it can very clearly show to be good, or a

means to our blessedness. Such things as are good simply because

they have been commanded or instituted, or as being symbols of something good,

are mere shadows which cannot be reckoned among actions that are the offspring

as it were, or fruit of a sound mind and of intellect. There is no need for me to go into this now

in more detail.

IV. Lastly, we see that the highest reward of the Divine law is the law itself, namely, to know God and

to love Him of our free choice, and with an undivided and fruitful spirit; while

its penalty is the absence of these things, and being in bondage to the flesh -

that is, having an inconstant and wavering spirit.

These points being noted, I must now inquire:

I. Whether by the natural light of reason we can conceive of God as a law-giver or

potentate ordaining laws for men?

II. What is the

teaching of Holy Writ concerning this natural light of reason and natural law?

III.

With what objects were ceremonies formerly instituted?

IV. Lastly, what is the good gained by knowing the

sacred histories and believing them?

Of the first two I will treat

in this chapter, of the remaining two in the following one.

Our conclusion about the first is easily deduced from

the nature of God's will, which is only distinguished from His understanding in relation to our intellect - that is, the will and the understanding of God are in reality one and the same,

and are only distinguished in relation to our thoughts which we form concerning

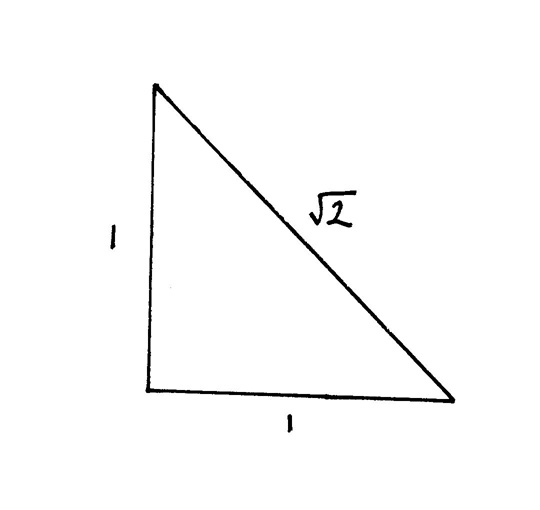

God's understanding. For instance, if we are only looking to the fact that the

nature of a triangle is from eternity contained in the Divine nature as an eternal verity, we say that God possesses the idea of a

triangle, or that He understands the nature of a triangle; but if afterwards we

look to the fact that the nature of a triangle is thus contained in the Divine

nature, solely by the necessity of the Divine nature, and not by the necessity

of the nature and essence of a triangle - in fact, that the necessity of a

triangle's essence and nature, in so far as they are conceived of as eternal verities, depends solely on the necessity of

the Divine nature and intellect, we then style God's will or decree, that

which before we styled His intellect. Wherefore we make one and the same affirmation concerning God when we say that He has from

eternity decreed that three angles of a triangle are

equal to two right angles, as when we say that He has understood it.

Hence the affirmations and the negations of God always involve necessity or truth; so

that, for example, if God said to Adam that He did not wish him to eat of the

tree of knowledge of good and evil, it would have involved a contradiction that

Adam should have been able to eat of it, and would therefore have been

impossible that he should have so eaten, for the Divine command would have

involved an eternal necessity and truth. But since Scripture

nevertheless narrates that God did give this command to Adam, and yet that none

the less Adam ate of the tree, we must perforce say that God revealed to Adam

the evil which would surely follow if he should eat of the tree, but did not

disclose that such evil would of necessity come to pass. Thus it was that Adam

took the revelation to be not an eternal and necessary truth, but a law - that is, an ordinance followed by gain or loss,

not depending necessarily on the nature of the act performed, but solely on the

will and absolute power of some potentate, so that the revelation in question was solely in relation to Adam,

and solely through his lack of knowledge a law, and God was, as it were, a

lawgiver and potentate. From the same cause, namely, from lack of knowledge, the

Decalogue in relation to the Hebrews was a law, for since they knew not the existence of God as an eternal truth, they must have taken as a law that which

was revealed to them in the Decalogue, namely, that God exists, and that God

only should be worshipped. But if God had spoken to them without the

intervention of any bodily means, immediately they would have perceived it not

as a law, but as an eternal truth.

What we have said about the Israelites and Adam,

applies also to all the prophets who wrote laws in God's name - they did not

adequately conceive God's decrees as eternal truths. For instance, we must say of Moses that from revelation, from the basis of what was revealed to him,

he perceived the method by which the Israelitish nation could best be united in

a particular territory, and could form a body politic or state, and further that he perceived the method by

which that nation could best be constrained to obedience; but he did not

perceive, nor was it revealed to him, that this method was absolutely the best,

nor that the obedience of the people in a certain strip of territory would

necessarily imply the end he had in view. Wherefore he perceived these things

not as eternal truths, but as precepts and ordinances, and he

ordained them as laws of God, and thus it came to be that he conceived God as a

ruler, a legislator, a king, as merciful, just, &c., whereas such qualities

are simply attributes of human nature, and utterly alien from the nature of the

Deity. Thus much we may affirm of the prophets who wrote laws in the name of

God; but we must not affirm it of Christ, for Christ, although He too seems to have

written laws in the name of God, must be taken to have had a clear and adequate

perception, for Christ was not so much a prophet as the mouthpiece of

God. For God made revelations to mankind through Christ as He had before done through angels - that is,

a created voice, visions, &c. It would be as unreasonable to say that God

had accommodated his revelations to the opinions of Christ as that He had before accommodated them to the

opinions of angels (that is, of a created voice or visions) as matters to be

revealed to the prophets, a wholly absurd hypothesis. Moreover, Christ was sent to teach not only the Jews but the

whole human race, and therefore it was not enough that His mind should be

accommodated to the opinions the Jews alone, but also to the opinion and

fundamental teaching common to the whole human race - in other words, to ideas universal and true. Inasmuch as God revealed

Himself to Christ, or to Christ's mind immediately, and not as to

the prophets through words and symbols, we must needs suppose that Christ perceived truly what was revealed, in other

words, He understood it, for a matter is understood when it is perceived simply by the mind

without words or symbols.

Christ, then, perceived (truly and adequately) what was

revealed, and if He ever proclaimed such revelations as laws, He did so because of the ignorance

and obstinacy of the people, acting in this respect the part of God; inasmuch as

He accommodated Himself to the comprehension of the people, and though He spoke

somewhat more clearly than the other prophets, yet He taught what was revealed

obscurely, and generally through parables, especially when He was speaking to

those to whom it was not yet given to understand the kingdom of heaven. (See

Matt. xiii:10, &c.) To those to whom it was given to understand the

mysteries of heaven, He doubtless taught His doctrines as eternal truths, and did not lay them down as laws, thus

freeing the minds of His hearers from the bondage of that law which He further

confirmed and established. Paul apparently points to this more than once (e.g.

Rom. vii:6, and iii:28), though he never himself seems to wish to speak openly,

but, to quote his own words (Rom. iii:6, and vi:19), "merely humanly." This he

expressly states when he calls God just, and it was doubtless in concession to

human weakness that he attributes mercy, grace, anger, and similar qualities to

God, adapting his language to the popular mind, or, as he puts it (1 Cor. iii:1,

2), to carnal men. In Rom. ix:18, he teaches undisguisedly that God's auger and

mercy depend not on the actions of men, but on God's own nature or will;

further, that no one is justified by the works of the law, but only by faith,

which he seems to identify with the full assent of the soul; lastly, that no one

is blessed unless he have in him the mind of Christ (Rom. viii:9), whereby he perceives the laws of

God as eternal truths. We conclude, therefore, that God is

described as a lawgiver or prince, and styled just, merciful, &c., merely in

concession to popular understanding, and the imperfection of popular knowledge;

that in reality God acts and directs all things simply by the necessity of His

nature and perfection, and that His decrees and volitions are eternal truths, and always involve necessity. So much

for the first point which I wished to explain and demonstrate.

Passing on to the second point, let us search the

sacred pages for their teaching concerning the light of nature and this Divine law. The first doctrine we find in the history

of the first man, where it is narrated that God commanded Adam not to eat of the

fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil; this seems to mean that God

commanded Adam to do and to seek after righteousness because it was good, not

because the contrary was evil: that is, to seek the good for its own sake, not

from fear of evil. We have seen that he who acts rightly from the true knowledge

and love of right, acts with freedom and constancy, whereas he who acts from

fear of evil, is under the constraint of evil, and acts in bondage under

external control. So that this commandment of God to Adam comprehends the whole

Divine natural law, and absolutely agrees with the dictates of the light of

nature; nay, it would be easy to explain on this basis the whole history or

allegory of the first man. But I prefer to pass over the subject in silence,

because, in the first place, I cannot be absolutely certain that my explanation

would be in accordance with the intention of the sacred writer; and, secondly,

because many do not admit that this history is an allegory, maintaining it to be

a simple narrative of facts. It will be better, therefore, to adduce other

passages of Scripture, especially such as were written by him, who speaks with

all the strength of his natural understanding, in which he surpassed all his

contemporaries, and whose sayings are accepted by the people as of equal weight

with those of the prophets. I mean Solomon, whose prudence and wisdom are commended in

Scripture rather than his piety and gift of prophecy. He, in his proverbs calls the human intellect

the well-spring of true life, and declares that misfortune is made up of folly.

"Understanding is a well-spring of life to him that hath it; but the instruction

of fools is folly," Prov. xvi. 22. Life being taken to mean the true life (as is

evident from Deut. xxx. 19), the fruit of the understanding consists only in the true life, and its

absence constitutes punishment. All this absolutely agrees with what was set out

in our fourth point concerning natural law. Moreover our position that it is the

well-spring of life, and that the intellect alone lays down laws for the wise, is plainly

taught by, the sage, for he says (Prov. xiii. 14): "The law of the wise is a

fountain of life " - that is, as we gather from the preceding text, the understanding. In chap. iii. 13, he expressly teaches

that the understanding renders man blessed and happy, and gives

him true peace of mind. "Happy is the man that findeth wisdom, and the man that

getteth understanding," for "Wisdom gives length of days, and

riches and honour; her ways are ways of pleasantness, and all her paths peace"

(iii 16, 17). According to Solomon, therefore, it is only, the wise who live in

peace and equanimity, not like the wicked whose minds drift hither and thither,

and (as Isaiah says, chap. lvii:20) "are like the troubled sea, for them there

is no peace."

Lastly, we should especially note the passage in chap.

ii. of Solomon's proverbs which most clearly confirms our

contention: "If thou criest after knowledge, and liftest up thy voice for understanding . . . then shalt thou understand the fear

of the Lord, and find the knowledge of God; for the Lord giveth wisdom; out of

His mouth cometh knowledge and understanding." These words clearly enunciate, that

wisdom or intellect alone teaches us to fear God wisely - that

is, to worship Him truly;, that wisdom and knowledge flow from God's mouth, and

that God bestows on us this gift; this we have already shown in proving that our

understanding and our knowledge depend on, spring from,

and are perfected by the idea or knowledge of God, and nothing else. Solomon goes on to say in so many words that this

knowledge contains and involves the true principles of ethics and politics:

"When wisdom entereth into thy heart, and knowledge is pleasant to thy soul,

discretion shall preserve thee, understanding shall keep thee, then shalt thou

understand righteousness, and judgment, and equity, yea every good path." All of

which is in obvious agreement with natural knowledge: for after we have come to

the understanding of things, and have tasted the excellence

of knowledge, she teaches us ethics and true virtue.

Thus the happiness and the peace of him who cultivates

his natural understanding lies, according to Solomon also, not so much under the dominion of fortune

(or God's external aid) as in inward personal virtue (or God's internal aid),

for the latter can to a great extent be preserved by vigilance, right action,

and thought.

Lastly, we must by no means pass over the passage in

Paul's Epistle to the Romans, i:20, in which he says: "For the invisible things

of God from the creation of the world are clearly seen, being understood by the

things that are made, even His eternal power and Godhead; so that they are without

excuse, because, when they knew God, they glorified Him not as God, neither were

they thankful." These words clearly show that everyone can by the light of

nature clearly understand the goodness and the eternal divinity of God, and can thence know and deduce

what they should seek for and what avoid; wherefore the Apostle says that they

are without excuse and cannot plead ignorance, as they certainly might if it

were a question of supernatural light and the incarnation, passion, and resurrection of Christ. "Wherefore," he goes on to say (ib. 24), "God

gave them up to uncleanness through the lusts of their own hearts;" and so on,

through the rest of the chapter, he describes the vices of ignorance, and sets

them forth as the punishment of ignorance. This obviously agrees with the verse

of Solomon, already quoted, "The instruction of fools is

folly," so that it is easy to understand why Paul says that the wicked are

without excuse. As every man sows so shall he reap: out of evil, evils

necessarily spring, unless they be wisely counteracted.

Thus we see that Scripture literally approves of the light of natural reason and the natural Divine law, and I have fulfilled the promises made at the beginning of this chapter.