Chapter 20

That in a Free State Every Man May Think What He Likes, and Say What He Thinks

If men's minds were as easily controlled as their tongues, every king

would sit safely on his throne, and government by compulsion would cease; for every subject

would shape his life according to the intentions of his rulers, and would esteem

a thing true or false, good or evil, just or unjust, in obedience to their

dictates. However, we have shown already (Chapter 17.) that no man's mind can

possibly lie wholly at the disposition of another, for no one can willingly

transfer his natural right of free reason and judgment, or be compelled so to do. For this

reason government which attempts to control minds is accounted

tyrannical, and it is considered an abuse of

sovereignty and a usurpation of the rights of subjects, to seek to prescribe

what shall be accepted as true, or rejected as false, or what opinions should

actuate men in their worship of God. All these questions fall within a man's natural right, which he cannot abdicate even with his

own consent.

I admit that the judgment can be

biased in many ways, and to an almost incredible degree, so that while exempt

from direct external control it may be so dependent on another man's words, that

it may fitly be said to be ruled by him; but although this influence is carried

to great lengths, it has never gone so far as to invalidate the statement, that

every man's understanding is his own, and that brains are as

diverse as palates.

Moses, not by fraud, but by Divine virtue, gained such

a hold over the popular judgment that he was accounted superhuman, and believed

to speak and act through the inspiration of the Deity; nevertheless, even he

could not escape murmurs and evil interpretations. How much less then can other

monarchs avoid them! Yet such unlimited power, if it exists at all, must belong

to a monarch, and least of all to a democracy, where the whole or a great part of the

people wield authority collectively. This is a fact which I think everyone can

explain for himself.

However unlimited, therefore, the power of a sovereign

may be, however implicitly it is trusted as the exponent of law and religion, it

can never prevent men from forming judgments according to their intellect, or being influenced by any given emotion. It

is true that it has the right to treat as enemies all men whose opinions do not,

on all subjects, entirely coincide with its own; but we are not discussing its

strict rights, but its proper course of action. I grant that it has the right to

rule in the most violent manner, and to put citizens to death for very trivial

causes, but no one supposes it can do this with the approval of sound judgment.

Nay, inasmuch as such things cannot be done without extreme peril to itself, we

may even deny that it has the absolute power to do them, or, consequently, the

absolute right; for the rights of the sovereign are limited by his power.

Since, therefore, no one can abdicate his freedom of

judgment and feeling; since every man is by indefeasible natural right the master of his own thoughts, it

follows that men thinking in diverse and contradictory fashions, cannot, without

disastrous results, be compelled to speak only according to the dictates of the

supreme power. Not even the most experienced, to say nothing of the multitude,

know how to keep silence. Men's common failing is to confide their plans to

others, though there be need for secrecy, so that a government would be most harsh which deprived the

individual of his freedom of saying and teaching what he thought; and would be

moderate if such freedom were granted. Still we cannot deny that authority may

be as much injured by words as by actions; hence, although the freedom we are

discussing cannot be entirely denied to subjects, its unlimited concession would

be most baneful; we must, therefore, now inquire, how far such freedom can and

ought to be conceded without danger to the peace of the state, or the power of the rulers; and this, as I said

at the beginning of Chapter 16., is my principal object.

It follows, plainly, from the explanation given above, of the foundations of a state, that the ultimate aim of government is not to rule, or restrain, by fear, nor to exact obedience, but contrariwise, to free every man from fear, that he may live in all possible security; in other words, to strengthen his natural right to exist and work - without injury to himself or others.

No, the object of government is not to change men from rational beings

into beasts or puppets, but to enable them to develop their minds and bodies in

security, and to employ their reason unshackled; neither showing hatred, anger, or

deceit, nor watched with the eyes of jealousy and injustice. In fact, the true

aim of government is liberty.

Now we have seen that in forming a state the power of making laws must either be vested in

the body of the citizens, or in a portion of them, or in one man. For, although

mens free judgments are very diverse, each one thinking that he alone knows

everything, and although complete unanimity of feeling and speech is out of the

question, it is impossible to preserve peace, unless individuals abdicate their

right of acting entirely on their own judgment.

Therefore, the individual justly cedes the right of free action, though not of free reason and judgment; no one can act against the

authorities without danger to the state, though his feelings and judgment may be at

variance therewith; he may even speak against them, provided that he does so

from rational conviction, not from fraud, anger, or hatred, and provided that he

does not attempt to introduce any change on his private authority.

For instance, supposing a man shows that a law is

repugnant to sound reason, and should therefore be repealed; if he submits

his opinion to the judgment of the authorities (who, alone, have the right of

making and repealing laws), and meanwhile acts in nowise contrary to that law,

he has deserved well of the state, and has behaved as a good citizen should; but if

he accuses the authorities of injustice, and stirs up the people against them,

or if he seditiously strives to abrogate the law without their consent, he is a

mere agitator and rebel.

Thus we see how an individual may declare and teach

what he believes, without injury to the authority of his rulers, or to the

public peace; namely, by leaving in their hands the entire power of legislation

as it affects action, and by doing nothing against their laws, though he be

compelled often to act in contradiction to what he believes, and openly feels,

to be best.

Such a course can be taken without

detriment to justice and dutifulness, nay, it is the one which a just and

dutiful man would adopt. We have shown that justice is dependent on the laws of

the authorities, so that no one who contravenes their accepted decrees can be

just, while the highest regard for duty, as we have pointed out in the preceding

chapter, is exercised in maintaining public peace and tranquillity; these could

not be preserved if every man were to live as he pleased; therefore it is no

less than undutiful for a man to act contrary to his country's laws, for if the

practice became universal the ruin of states would necessarily follow.

Hence, so long as a man acts in obedience to the laws

of his rulers, he in nowise contravenes his reason, for in obedience to reason he transferred the

right of controlling his actions from his own hands to

theirs. This doctrine we can confirm from actual custom, for in a conference of

great and small powers, schemes are seldom carried unanimously, yet all unite in

carrying out what is decided on, whether they voted for or against. But I return

to my proposition.

From the fundamental notions of a state, we have discovered how a man may exercise free

judgment without detriment to the supreme power: from the same premises we can

no less easily determine what opinions would be seditious. Evidently those which

by their very nature nullify the compact by which the right of free action was

ceded. For instance, a man who holds that the supreme power has no rights over

him, or that promises ought not to be kept, or that everyone should live as he

pleases, or other doctrines of this nature in direct opposition to the above-

mentioned contract, is seditious, not so much from his actual opinions and

judgment, as from the deeds which they involve; for he who maintains such

theories abrogates the contract which tacitly, or openly, he made with his

rulers. Other opinions which do not involve acts violating the contract, such as

revenge, anger, and the like, are not seditious, unless it be in some corrupt state, where superstitious and ambitious persons, unable to endure

men of learning, are so popular with the multitude that their word is more

valued than the law.

However, I do not deny that there are some doctrines

which, while they are apparently only concerned with abstract truths and falsehoods, are yet propounded and

published with unworthy motives. This question we have discussed in Chapter 15.,

and shown that reason should nevertheless remain unshackled. If we

hold to the principle that a man's loyalty to the state should be judged, like his loyalty to God, from

his actions only - namely, from his charity towards his neighbours; we cannot

doubt that the best government will allow freedom of philosophical speculation no less than of religious

belief. I confess that from such freedom inconveniences may sometimes arise, but

what question was ever settled so wisely that no abuses could possibly spring

therefrom? He who seeks to regulate everything by law, is more likely to arouse

vices than to reform them. It is best to grant what cannot be abolished, even

though it be in itself harmful. How many evils spring from luxury, envy,

avarice, drunkenness, and the like, yet these are tolerated - vices as they are

- because they cannot be prevented by legal enactments. How much more then

should free thought be granted, seeing that it is in itself a virtue and that it

cannot be crushed! Besides, the evil results can easily be checked, as I will

show, by the secular authorities, not to mention that such freedom is absolutely

necessary for progress in science and the liberal arts: for no man follows such

pursuits to advantage unless his judgment be entirely free and unhampered.

But let it be granted that freedom may be crushed, and

men be so bound down, that they do not dare to utter a whisper, save at the

bidding of their rulers; nevertheless this can never be carried to the pitch of

making them think according to authority, so that the necessary consequences

would be that men would daily be thinking one thing and saying another, to the

corruption of good faith, that mainstay of government, and to the fostering of hateful flattery

and perfidy, whence spring stratagems, and the corruption of every good art.

It is far from possible to impose uniformity of

speech, for the more rulers strive to curtail freedom of speech, the more

obstinately are they resisted; not indeed by the avaricious, the flatterers, and

other numskulls, who think supreme salvation consists in filling their stomachs

and gloating over their money-bags, but by those whom good education, sound

morality, and virtue have rendered more free. Men, as generally constituted, are

most prone to resent the branding as criminal of opinions which they believe to

be true, and the proscription as wicked of that which inspires them with piety

towards God and man; hence they are ready to forswear the laws and conspire

against the authorities, thinking it not shameful but honourable to stir up

seditions and perpetuate any sort of crime with this end in view. Such being the

constitution of human nature, we see that laws directed against opinions affect

the generous minded rather than the wicked, and are adapted less for coercing

criminals than for irritating the upright; so that they cannot be maintained

without great peril to the state.

Moreover, such laws are almost always useless, for

those who hold that the opinions proscribed are sound, cannot possibly obey the

law; whereas those who already reject them as false, accept the law as a kind of

privilege, and make such boast of it, that authority is powerless to repeal it,

even if such a course be subsequently desired.

To these considerations may be added what we said in

Chapter 18. in treating of the history of the Hebrews. And, lastly, how many

schisms have arisen in the Church from the attempt of the authorities to decide

by law the intricacies of theological controversy! If men were not allured by

the hope of getting the law and the authorities on their side, of triumphing

over their adversaries in the sight of an applauding multitude, and of acquiring

honourable distinctions, they would not strive so maliciously, nor would such

fury sway their minds. This is taught not only by reason but by daily examples,

for laws of this kind prescribing what every man shall believe and forbidding

anyone to speak or write to the contrary, have often been passed, as sops or

concessions to the anger of those who cannot tolerate men of enlightenment, and

who, by such harsh and crooked enactments, can easily turn the devotion of the

masses into fury and direct it against whom they will.

How much better would it be to restrain popular anger

and fury, instead of passing useless laws, which can only be broken by those who

love virtue and the liberal arts, thus paring down the state till it is too small to harbour men of talent.

What greater misfortune for a state can be conceived then that honourable men should

be sent like criminals into exile, because they hold diverse opinions which they

cannot disguise? What, I say, can be more hurtful than that men who have

committed no crime or wickedness should, simply because they are enlightened, be

treated as enemies and put to death, and that the scaffold, the terror of

evil-doers, should become the arena where the highest examples of tolerance and

virtue are displayed to the people with all the marks of ignominy that authority

can devise?

He that knows himself to be upright does not fear the

death of a criminal, and shrinks from no punishment; his mind is not wrung with

remorse for any disgraceful deed: he holds that death in a good cause is no

punishment, but an honour, and that death for freedom is glory.

What purpose then is served by the death of such men,

what example in proclaimed? the cause for which they die is unknown to the idle

and the foolish, hateful to the turbulent, loved by the upright. The only lesson

we can draw from such scenes is to flatter the persecutor, or else to imitate

the victim.

If formal assent is not to be esteemed above

conviction, and if governments are to retain a firm hold of authority and

not be compelled to yield to agitators, it is imperative that freedom of

judgment should be granted, so that men may live together in harmony, however

diverse, or even openly contradictory their opinions may be. We cannot doubt

that such is the best system of government and open to the fewest objections, since it

is the one most in harmony with human nature. In a democracy (the most natural form of government, as we

have shown in Chapter 16.) everyone submits to the control of authority over his

actions, but not over his judgment and reason; that is, seeing that all cannot think alike,

the voice of the majority has the force of law, subject to repeal if

circumstances bring about a change of opinion. In proportion as the power of

free judgment is withheld we depart from the natural condition of mankind, and

consequently the government becomes more tyrannical.

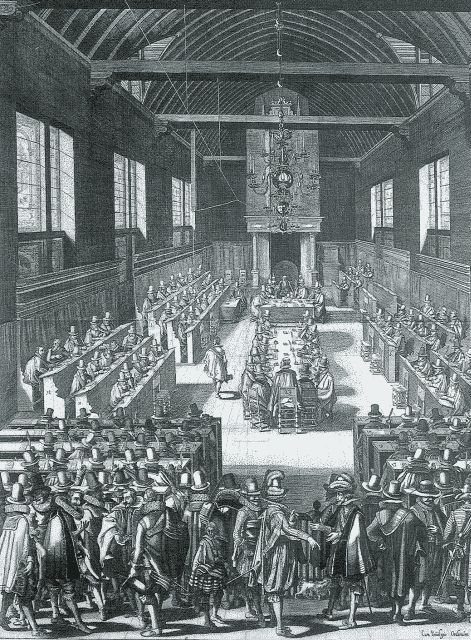

In order to prove that from such freedom no inconvenience arises, which cannot easily be checked by the exercise of the sovereign power, and that men's actions can easily be kept in bounds, though their opinions be at open variance, it will be well to cite an example. Such an one is not very, far to seek. The city of Amsterdam reaps the fruit of this freedom in its own great prosperity and in the admiration of all other people. For in this most flourishing state, and most splendid city, men of every, nation and religion live together in the greatest harmony, and ask no questions before trusting their goods to a fellow- citizen, save whether he be rich or poor, and whether he generally acts honestly, or the reverse. His religion and sect is considered of no importance: for it has no effect before the judges in gaining or losing a cause, and there is no sect so despised that its followers, provided that they harm no one, pay every man his due, and live uprightly, are deprived of the protection of the magisterial authority.

On the other hand, when the religious controversy

between Remonstrants and Counter-Remonstrants began to be taken up by

politicians and the States, it grew into a schism, and abundantly showed that

laws dealing with religion and seeking to settle its controversies are much more

calculated to irritate than to reform, and that they give rise to extreme

licence: further, it was seen that schisms do not originate in a love of truth,

which is a source of courtesy and gentleness, but rather in an inordinate desire

for supremacy, From all these considerations it is clearer than the sun at

noonday, that the true schismatics are those who condemn other men's writings,

and seditiously stir up the quarrelsome masses against their authors, rather

than those authors themselves, who generally write only for the learned, and

appeal solely to reason. In fact, the real disturbers of the peace are

those who, in a free state, seek to curtail the liberty of judgment which

they are unable to tyrannize over.

I have thus shown:-

I. That it is impossible to deprive men of the liberty of saying what

they think.

II. That such liberty can be conceded to every man without injury to

the rights and authority of the sovereign power, and that every man may retain

it without injury to such rights, provided that he does not presume upon it to

the extent of introducing any new rights into the state, or acting in any way contrary, to the existing

laws.

III. That every man may enjoy this liberty without detriment to the

public peace, and that no inconveniences arise therefrom which cannot easily be

checked.

IV. That every man may enjoy it without injury to his allegiance.

V. That laws dealing with speculative problems are entirely useless.

VI. Lastly, that not only may such liberty be granted without

prejudice to the public peace, to loyalty, and to the rights of rulers, but that

it is even necessary, for their preservation. For when people try to take it

away, and bring to trial, not only the acts which alone are capable of

offending, but also the opinions of mankind, they only succeed in surrounding

their victims with an appearance of martyrdom, and raise feelings of pity and

revenge rather than of terror. Uprightness and good faith are thus corrupted,

flatterers and traitors are encouraged, and sectarians triumph, inasmuch as

concessions have been made to their animosity, and they have gained the state

sanction for the doctrines of which they are the interpreters. Hence they

arrogate to themselves the state authority and rights, and do not scruple to

assert that they have been directly chosen by God, and that their laws are

Divine, whereas the laws of the state are human, and should therefore yield obedience

to the laws of God - in other words, to their own laws. Everyone must see that

this is not a state of affairs conducive to public welfare. Wherefore, as we

have shown in Chapter 18., the safest way for a state is to lay down the rule that religion is

comprised solely in the exercise of charity and justice, and that the rights of

rulers in sacred, no less than in secular matters, should merely have to do with

actions, but that every man should think what he likes and say what he thinks.

I have thus fulfilled the task I set myself in this treatise. It remains only to call attention to the fact that I have written nothing which I do not most willingly submit to the examination and approval of my country's rulers; and that I am willing to retract anything which they shall decide to be repugnant to the laws, or prejudicial to the public good. I know that I am a man, and as a man liable to error, but against error I have taken scrupulous care, and have striven to keep in entire accordance with the laws of my country, with loyalty, and with morality.