Chapter 17

It is Shown that No One Can, or Need Transfer All His Rights to the Sovereign Power. Of the Hebrew Republic, As It Was During the Lifetime of Moses, and After His Death, Till the Foundation of the Monarchy; and Of Its Excellence. Lastly. Of the Causes Why the Theocratic Republic Fell, and Why It Could Hardly Have Continued Without Dissension.

The theory put forward in the last chapter, of the

universal rights of the sovereign power, and of the natural rights of the individual transferred thereto,

though it corresponds in many respects with actual practice, and though practice

may be so arranged as to conform to it more and more, must nevertheless always

remain in many respects purely ideal. No one can ever so utterly transfer to

another his power and, consequently, his rights, as to cease to be a man; nor can there ever be

a power so sovereign that it can carry out every possible wish. It will always

be vain to order a subject to hate what he believes brings him advantage, or to

love what brings him loss, or not to be offended at insults, or not to wish to

be free from fear, or a hundred other things of the sort, which necessarily

follow from the laws of human nature. So much, I think, is abundantly shown by

experience: for men have never so far ceded their power as to cease to be an

object of fear to the rulers who received such power and right; and dominions

have always been in as much danger from their own subjects as from external

enemies. If it were really the case, that men could be deprived of their natural rights so utterly as never to have any further

influence on affairs [N29], except with the permission of the holders of

sovereign right, it would then be possible to maintain with impunity the most

violent tyranny, which, I suppose, no one would for an instant

admit.

We must, therefore, grant that

every man retains some part of his right, in dependence on his own decision, and no one

else's.

However, in order correctly to

understand the extent of the sovereign's right and power, we must take notice

that it does not cover only those actions to which it can compel men by fear,

but absolutely every action which it can induce men to perform: for it is the

fact of obedience, not the motive for obedience, which makes a man a subject.

Whatever be the cause which

leads a man to obey the commands of the sovereign, whether it be fear or hope,

or love of his country, or any other emotion - the fact remains that the man

takes counsel with himself, and nevertheless acts as his sovereign orders. We

must not, therefore, assert that all actions resulting from a man's deliberation

with himself are done in obedience to the rights of the individual rather than the sovereign: as

a matter of fact, all actions spring from a man's deliberation with himself,

whether the determining motive be love or fear of punishment; therefore, either

dominion does not exist, and has no rights over its subjects, or else it extends

over every instance in which it can prevail on men to decide to obey it.

Consequently, every action which a subject performs in accordance with the

commands of the sovereign, whether such action springs from love, or fear, or

(as is more frequently the case) from hope and fear together, or from reverence.

compounded of fear and admiration, or, indeed, any motive whatever, is performed

in virtue of his submission to the sovereign, and not in virtue of his own

authority.

This point is made still more

clear by the fact that obedience does not consist so much in the outward act as

in the mental state of the person obeying; so that he is most under the dominion

of another who with his whole heart determines to obey another's commands; and

consequently the firmest dominion belongs to the sovereign who has most

influence over the minds of his subjects; if those who are most feared possessed

the firmest dominion, the firmest dominion would belong to the subjects of a tyrant, for they are always greatly feared by their

ruler. Furthermore, though it is impossible to govern the mind as completely as

the tongue, nevertheless minds are, to a certain extent, under the control of

the sovereign, for he can in many ways bring about that the greatest part of his

subjects should follow his wishes in their beliefs, their loves, and their

hates. Though such emotions do not arise at the express command of the sovereign

they often result (as experience shows) from the authority of his power, and

from his direction ; in other words, in virtue of his right; we may, therefore,

without doing violence to our understanding, conceive men who follow the

instigation of their sovereign in their beliefs, their loves, their hates, their

contempt, and all other emotions whatsoever.

Though the powers of government, as thus conceived, are sufficiently ample,

they can never become large enough to execute every possible wish of their

possessors. This, I think, I have already shown clearly enough. The method of

forming a dominion which should prove lasting I do not, as I have said, intend

to discuss, but in order to arrive at the object I have in view, I will touch on

the teaching of Divine revelation to Moses in this respect, and we will consider the history

and the success of the Jews, gathering therefrom what should be the chief

concessions made by sovereigns to their subjects with a view to the security and

increase of their dominion.

That the preservation of a state chiefly depends on the subjects' fidelity and

constancy in carrying out the orders they receive, is most clearly taught both

by reason and experience; how subjects ought to be guided

so as best to preserve their fidelity and virtue is not so obvious. All, both

rulers and ruled, are men, and prone to follow after their lusts. The fickle

disposition of the multitude almost reduces those who have experience of it to

despair, for it is governed solely by emotions, not by reason: it rushes

headlong into every enterprise, and is easily corrupted either by avarice or

luxury: everyone thinks himself omniscient and wishes to fashion all things to

his liking, judging a thing to be just or unjust, lawful or unlawful, according

as he thinks it will bring him profit or loss: vanity leads him to despise his

equals, and refuse their guidance: envy of superior fame or fortune (for such

gifts are never equally distributed) leads him to desire and rejoice in his

neighbour's downfall. I need not go through the whole list, everyone knows

already how much crime results from disgust at the present - desire for change,

headlong anger, and contempt for poverty - and how men's minds are engrossed and

kept in turmoil thereby.

To guard against all these

evils, and form a dominion where no room is left for deceit; to frame our

institutions so that every man, whatever his disposition, may prefer public

right to private advantage, this is the task and this the toil. Necessity is

often the mother of invention, but she has never yet succeeded in framing a

dominion that was in less danger from its own citizens than from open enemies,

or whose rulers did not fear the latter less than the former. Witness the state

of Rome, invincible by her enemies, but many times conquered and sorely

oppressed by her own citizens, especially in the war between Vespasian and

Vitellius. (See Tacitus, Hist. bk. iv. for a description of the pitiable state

of the city.)

Alexander thought prestige

abroad more easy to acquire than prestige at home, and believed that his

greatness could be destroyed by his own followers. Fearing such a disaster, he

thus addressed his friends: "Keep me safe from internal treachery and domestic

plots, and I will front without fear the dangers of battle and of war. Philip

was more secure in the battle array than in the theatre: he often escaped from

the hands of the enemy, he could not escape from his own subjects. If you think

over the deaths of kings, you will count up more who have died by the assassin

than by the open foe." (Q. Curtius, chap. vi.)

For the sake of making themselves secure, kings who seized the throne in ancient

times used to try to spread the idea that they were descended from the immortal

gods, thinking that if their subjects and the rest of mankind did not look on

them as equals, but believed them to be gods, they would willingly submit to

their rule, and obey their commands. Thus Augustus persuaded the Romans that he

was descended from AEneas, who was the son of Venus, and numbered among the

gods. "He wished himself to be worshipped in temples, like the gods, with

flamens and priests." (Tacitus, Ann. i. 10.)

Alexander wished to be saluted

as the son of Jupiter, not from motives of pride but of policy, as he showed by

his answer to the invective of Hermolaus: "It is almost laughable," said he,

that Hermolaus asked me to contradict Jupiter, by whose oracle I am recognized.

Am I responsible for the answers of the gods? It offered me the name of son;

acquiescence was by no means foreign to my present designs. Would that the

Indians also would believe me to be a god! Wars are carried through by prestige,

falsehoods that are believed often gain the force of truth." (Curtius, viii,.

Para, 8.) In these few words he cleverly contrives to palm off a fiction on the

ignorant, and at the same time hints at the motive for the deception.

Cleon, in his speech persuading

the Macedonians to obey their king, adopted a similar device: for after going

through the praises of Alexander with admiration, and recalling his merits, he

proceeds, "the Persians are not only pious, but prudent in worshipping their

kings as gods: for kingship is the shield of public safety," and he ends thus,

"I, myself, when the king enters a banquet hall, should prostrate my body on the

ground; other men should do the like, especially those who are wise " (Curtius,

viii. Para. 66). However, the Macedonians were more prudent - indeed, it is only

complete barbarians who can be so openly cajoled, and can suffer themselves to

be turned from subjects into slaves without interests of their own. Others,

notwithstanding, have been able more easily to spread the belief that kingship

is sacred, and plays the part of God on the earth, that it has been instituted

by God, not by the suffrage and consent of men; and that it is preserved and

guarded by Divine special providence and aid. Similar fictions have been

promulgated by monarchs, with the object of strengthening their

dominion, but these I will pass over, and in order to arrive at my main purpose,

will merely recall and discuss the teaching on the subject of Divine revelation to Moses in ancient times.

We have said in Chap. 5. that

after the Hebrews came up out of Egypt they were not bound by the law and right

of any other nation, but were at liberty to institute any new rites at their

pleasure, and to occupy whatever territory they chose. After their liberation

from the intolerable bondage of the Egyptians, they were bound by no covenant to

any man; and, therefore, every man entered into his natural right, and was free to retain it or to give it

up, and transfer it to another. Being, then, in the state of nature, they

followed the advice of Moses, in whom they chiefly trusted, and decided to

transfer their right to no human being, but only to God; without

further delay they all, with one voice, promised to obey all the commands of the

Deity, and to acknowledge no right that He did not proclaim as such by prophetic

revelation. This promise, or transference of right to God, was effected in the same manner as we

have conceived it to have been in ordinary societies, when men agree to divest

themselves of their natural rights. It is, in fact, in virtue of a set

covenant, and an oath (see Exod. xxxiv:10), that the Jews freely, and not under

compulsion or threats, surrendered their rights and transferred them to God. Moreover, in order

that this covenant might be ratified and settled, and might be free from all

suspicion of deceit, God did not enter into it till the Jews had had experience

of His wonderful power by which alone they had been, or could be, preserved in a

state of prosperity (Exod. xix:4, 5). It is because they believed that nothing

but God's power could preserve them that they surrendered to God the natural

power of self-preservation, which they formerly, perhaps, thought they

possessed, and consequently they surrendered at the same time all their natural right.

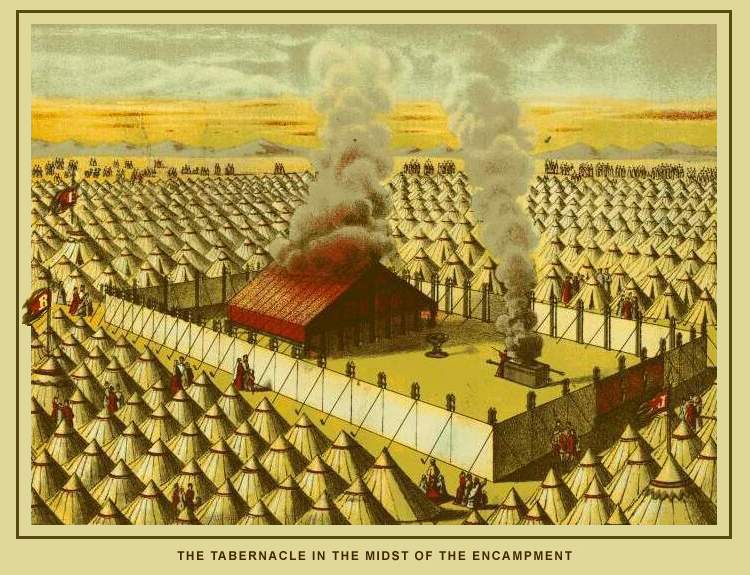

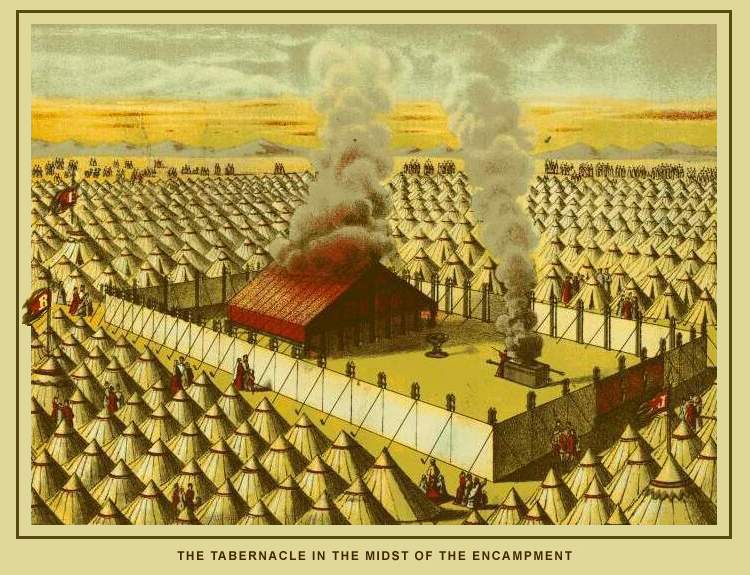

God alone, therefore, held

dominion over the Hebrews, whose state was in virtue of the covenant called God's

kingdom, and God was said to be their king; consequently the enemies of the Jews

were said to be the enemies of God, and the citizens who tried to seize the

dominion were guilty of treason against God; and, lastly, the laws of the state were called the laws and commandments of God.

Thus in the Hebrew state the civil and religious authority, each

consisting solely of obedience to God, were one and the same. The dogmas of

religion were not precepts, but laws and ordinances; piety was regarded as the

same as loyalty, impiety as the same as disaffection. Everyone who fell away

from religion ceased to be a citizen, and was, on that ground alone, accounted

an enemy: those who died for the sake of religion, were held to have died for

their country; in fact, between civil and religious law and right there was no

distinction whatever. For this reason the government could be called a Theocracy, inasmuch as the citizens were not bound by

anything save the revelations of God.

However, this state of things

existed rather in theory than in practice, for it will appear from what we are

about to say, that the Hebrews, as a matter of fact, retained absolutely in

their own hands the right of sovereignty: this is shown by the method and plan

by which the government was carried on, as I will now explain.

Inasmuch as the Hebrews did not

transfer their rights to any other person but, as in a democracy, all surrendered their rights equally, and

cried out with one voice, "Whatsoever God shall speak (no mediator or mouthpiece

being named) that will we do," it follows that all were equally bound by the

covenant, and that all had an equal right to consult the Deity, to accept and to

interpret His laws, so that all had an exactly equal share in the government. Thus at first they all approached God

together, so that they might learn His commands, but in this first salutation,

they were so thoroughly terrified and so astounded to hear God speaking, that

they thought their last hour was at hand: full of fear, therefore, they went

afresh to Moses, and said, "Lo, we have heard God speaking in the

fire, and there is no cause why we should wish to die: surely this great fire

will consume us: if we hear again the voice of God, we shall surely die. Thou,

therefore, go near, and hear all the words of our God, and thou (not God) shalt

speak with us: all that God shall tell us, that will we hearken to and perform."

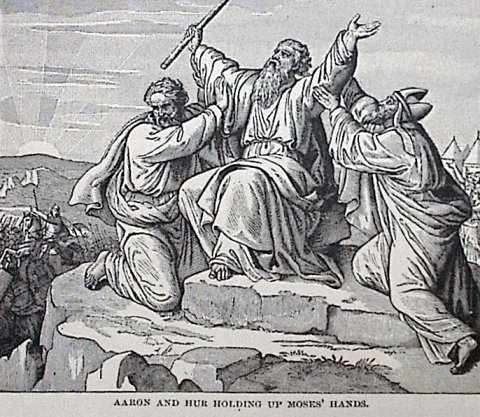

They thus clearly abrogated their former covenant, and absolutely transferred to Moses their right to consult God and interpret His commands: for they do not here promise obedience to all that God shall tell them, but to all that God shall tell Moses (see Deut. v:20 after the Decalogue, and chap. xviii:15, 16). Moses, therefore, remained the sole promulgator and interpreter of the Divine laws, and consequently also the sovereign judge, who could not be arraigned himself, and who acted among the Hebrews the part, of God; in other words, held the sovereign kingship: he alone had the right to consult God, to give the Divine answers to the people, and to see that they were carried out. I say he alone, for if anyone during the life of Moses was desirous of preaching anything in the name of the Lord, he was, even if a true prophet, considered guilty and a usurper of the sovereign right (Numb. xi:28) [N30]. We may here notice, that though the people had elected Moses, they could not rightfully elect Moses's successor; for having transferred to Moses their right of consulting God, and absolutely promised to regard him as a Divine oracle, they had plainly forfeited the whole of their right, and were bound to accept as chosen by God anyone proclaimed by Moses as his successor. If Moses had so chosen his successor, who like him should wield the sole right of government, possessing the sole right of consulting God, and consequently of making and abrogating laws, of deciding on peace or war, of sending ambassadors, appointing judges - in fact, discharging all the functions of a sovereign, the state would have become simply a monarchy, only differing from other monarchies in the fact, that the latter are, or should be, carried on in accordance with God's decree, unknown even to the monarch, whereas the Hebrew monarch would have been the only person to whom the decree was revealed. A difference which increases, rather than diminishes the monarch's authority. As far as the people in both cases are concerned, each would be equally subject, and equally ignorant of the Divine decree, for each would be dependent on the monarch's words, and would learn from him alone, what was lawful or unlawful: nor would the fact that the people believed that the monarch was only issuing commands in accordance with God's decree revealed to him, make it less in subjection, but rather more. However, Moses elected no such successor, but left the dominion to those who came after him in a condition which could not be called a popular government, nor an aristocracy, nor a monarchy, but a Theocracy. For the right of interpreting laws was vested in one man, while the right and power of administering the state according to the laws thus interpreted, was vested in another man (see Numb. xxvii:21) [N31].

[Note N29]: "If men could lose their natural rights so as to be absolutely unable for the future to oppose the will of the sovereign" Two common soldiers undertook to change the Roman dominion, and did change it. (Tacitus, Hist. i:7.)

[Note N30]: See Numbers xi. 28. In this passage it is written that two men prophesied in the camp, and that Joshua wished to punish them. This he would not have done, if it had been lawful for anyone to deliver the Divine oracles to the people without the consent of Moses. But Moses thought good to pardon the two men, and rebuked Joshua for exhorting him to