Chapter 16

Of the Foundations of a State: Of the Natural and

Civil Rights of Individuals;

and Of the Rights of the Sovereign

Power

Hitherto our care has been to separate philosophy from theology, and to show the freedom of thought which such

separation insures to both. It is now time to determine the limits to which such

freedom of thought and discussion may extend itself in the ideal state. For the due consideration of this question we

must examine the foundations of a State, first turning our attention to the natural rights of individuals, and afterwards to religion and the state as a whole.

By the right and ordinance of nature, I merely mean those

natural laws wherewith we conceive every individual to be conditioned by nature, so as to live

and act in a given way. For instance, fishes are naturally conditioned for

swimming, and the greater for devouring the less; therefore fishes enjoy the

water, and the greater devour the less by sovereign natural right. For it is certain that nature, taken in

the abstract, has sovereign right to do anything, she can; in other words, her right is co-extensive with her power. The power of

nature is the power of God, which has sovereign right over all things; and, inasmuch as the power of

nature is simply the aggregate of the powers of all her individual components,

it follows that every, individual has sovereign right to do all that he can; in other words, the rights

of an individual extend to the utmost limits of his power as it has been

conditioned. Now it is the sovereign law and right of nature that each individual should endeavour to preserve itself as it

is, without regard to anything but itself ; therefore this sovereign law and right belongs to every individual, namely, to exist and act according to its

natural conditions. We do not here acknowledge any difference between mankind

and other individual natural entities, nor between men endowed

with reason and those to whom reason is unknown; nor between

fools, madmen, and sane men. Whatsoever an individual does by the laws of its

nature it has a sovereign right to do, inasmuch as it acts as it was conditioned

by nature, and cannot act otherwise. Wherefore among men, so long as they are

considered as living under the sway of nature, he who does not yet know reason, or who has not yet acquired the habit of

virtue, acts solely according to the laws of his desire with as sovereign a right as he who orders his life entirely by the laws of

reason.

That is, as the wise man has sovereign right to do all that reason dictates, or to live according to the laws of

reason, so also the ignorant and foolish man has sovereign right to do all that desire dictates, or to live according to the laws of

desire. This is identical with the teaching of Paul, who acknowledges that

previous to the law - that is, so long as men are considered of as living under

the sway of nature, there is no sin.

The natural right of the individual man is thus determined, not by sound reason, but by desire and power. All are not naturally conditioned so

as to act according to the laws and rules of reason; nay, on the contrary, all

men are born ignorant, and before they can learn the right way of life and

acquire the habit of virtue, the greater part of their life, even if they have

been well brought up, has passed away. Nevertheless, they are in the meanwhile

bound to live and preserve themselves as far as they can by the unaided impulses

of desire. Nature has given them no other guide, and has

denied them the present power of living according to sound reason; so that they are no more bound to live by the

dictates of an enlightened mind, than a cat is bound to live by the laws of the

nature of a lion.

Whatsoever, therefore, an individual (considered as under the sway of nature)

thinks useful for himself, whether led by sound reason or impelled by the passions, that he has a

sovereign right to seek and to take for himself as he best can,

whether by force, cunning, entreaty, or any other means; consequently he may

regard as an enemy anyone who hinders the accomplishment of his purpose.

It follows from what we have said that the right and ordinance of nature, under which all men are

born, and under which they mostly live, only prohibits such things as no one desires, and no one can attain: it does not forbid

strife, nor hatred, nor anger, nor deceit, nor, indeed, any of the means

suggested by desire.

This we need not wonder at, for nature is not bounded

by the laws of human reason, which aims only at man's true benefit and

preservation; her limits are infinitely wider, and have reference to the eternal order of nature, wherein man is but a speck; it

is by the necessity of this alone that all individuals are conditioned for living and acting in a

particular way. If anything, therefore, in nature seems to us ridiculous,

absurd, or evil, it is because we only know in part, and are almost entirely

ignorant of the order and interdependence of nature as a whole, and also because

we want everything to be arranged according to the dictates of our human reason; in reality that which reason considers evil, is

not evil in respect to the order and laws of nature as a whole, but only in

respect to the laws of our reason.

Nevertheless, no one can doubt that it is much better for us to live according to the laws and assured dictates of reason, for, as we said, they have men's true good for their object. Moreover, everyone wishes to live as far as possible securely beyond the reach of fear, and this would be quite impossible so long as everyone did everything he liked, and reason's claim was lowered to a par with those of hatred and anger; there is no one who is not ill at ease in the midst of enmity, hatred, anger, and deceit, and who does not seek to avoid them as much as he can. When we reflect that men without mutual help, or the aid of reason, must needs live most miserably, as we clearly proved in Chap. 5., we shall plainly see that men must necessarily come to an agreement to live together as securely and well as possible if they are to enjoy as a whole the rights which naturally belong to them as individuals, and their life should be no more conditioned by the force and desire of individuals, but by the power and will of the whole body. This end they will be unable to attain if desire be their only guide (for by the laws of desire each man is drawn in a different direction); they must, therefore, most firmly decree and establish that they will be guided in everything by reason (which nobody will dare openly to repudiate lest he should be taken for a madman), and will restrain any desire which is injurious to a man's fellows, that they will do to all as they would be done by, and that they will defend their neighbour's rights as their own.

How such a compact as this should be entered into,

how ratified and established, we will now inquire.

Now it is a universal law of human nature that no one

ever neglects anything which he judges to be good, except with the hope of

gaining a greater good, or from the fear of a greater evil; nor does anyone

endure an evil except for the sake of avoiding a greater evil, or gaining a

greater good. That is, everyone will, of two goods, choose that which he thinks

the greatest; and, of two evils, that which he thinks the least. I say advisedly

that which he thinks the greatest or the least, for it does not necessarily

follow that he judges right. This law is so deeply implanted in the human mind that it ought to be counted among eternal truths and axioms.

As a necessary consequence of the principle just

enunciated, no one can honestly promise to forego the right which he has over all things [N26], and in

general no one will abide by his promises, unless under the fear of a greater

evil, or the hope of a greater good. An example will make the matter clearer.

Suppose that a robber forces me to promise that I will give him my goods at his

will and pleasure. It is plain (inasmuch as my natural right is, as I have shown, co-extensive with my

power) that if I can free myself from this robber by stratagem, by assenting to

his demands, I have the natural right to do so, and to pretend to accept his

conditions. Or again, suppose I have genuinely promised someone that for the

space of twenty days I will not taste food or any nourishment; and suppose I

afterwards find that was foolish, and cannot be kept without very great injury

to myself; as I am bound by natural law and right to choose the least of two evils, I have complete

right to break my compact, and act as if my promise had never been uttered. I

say that I should have perfect natural right to do so, whether I was actuated by true

and evident reason, or whether I was actuated by mere opinion in

thinking I had promised rashly; whether my reasons were true or false, I should

be in fear of a greater evil, which, by the ordinance of nature, I should strive

to avoid by every means in my power.

We may, therefore, conclude that a compact is only

made valid by its utility, without which it becomes null and void. It is,

therefore, foolish to ask a man to keep his faith with us for ever, unless we

also endeavour that the violation of the compact we enter into shall involve for

the violator more harm than good. This consideration should have very great

weight in forming a state. However, if all men could be easily led by reason alone, and could recognize what is best and most

useful for a state, there would be no one who would not forswear

deceit, for everyone would keep most religiously to their compact in their

desire for the chief good, namely, the preservation of the state, and would

cherish good faith above all things as the shield and buckler of the

commonwealth. However, it is far from being the case that all men can always be

easily led by reason alone; everyone is drawn away by his pleasure,

while avarice, ambition, envy, hatred, and the like so engross the mind that,

reason has no place therein. Hence, though men make promises with all the

appearances of good faith, and agree that they will keep to their engagement, no

one can absolutely rely on another man's promise unless there is something

behind it. Everyone has by nature a right to act deceitfully. and to break his compacts,

unless he be restrained by the hope of some greater good, or the fear of some

greater evil.

However, as we have shown that the natural right of the individual is only limited by his power, it is clear

that by transferring, either willingly or under compulsion, this power into the

hands of another, he in so doing necessarily cedes also a part of his right; and further, that the Sovereign right over all

men belongs to him who has sovereign power, wherewith he can compel men by

force, or restrain them by threats of the universally feared punishment of

death; such sovereign right he will retain only so long as he can maintain

his power of enforcing his will; otherwise he will totter on his throne, and no

one who is stronger than he will be bound unwillingly to obey him.

In this manner a society can be formed without any violation of natural right, and the covenant can always be strictly

kept - that is, if each individual hands over the whole of his power to the body

politic, the latter will then possess sovereign natural right over all things; that is, it will have

sole and unquestioned dominion, and everyone will be bound to obey, under pain

of the severest punishment. A body politic of this kind is called a Democracy, which may be defined as a society which wields all its power as a whole. The

sovereign power is not restrained by any laws, but everyone is bound to obey it

in all things; such is the state of things implied when men either tacitly or

expressly handed over to it all their power of self-defence, or in other words,

all their right. For if they had wished to retain any right for themselves, they ought to have taken

precautions for its defence and preservation; as they have not done so, and

indeed could not have done so without dividing and consequently ruining the state, they placed themselves absolutely at the mercy

of the sovereign power; and, therefore, having acted (as we have shown) as reason and necessity demanded, they are obliged to

fulfil the commands of the sovereign power, however absurd these may be, else

they will be public enemies, and will act against reason, which urges the

preservation of the state as a primary duty. For reason bids us choose the least of two evils.

Furthermore, this danger of submitting absolutely to

the dominion and will of another, is one which may be incurred with a light

heart: for we have shown that sovereigns only possess this right of imposing

their will, so long as they have the full power to enforce it: if such power be

lost their right to command is lost also, or lapses to those who have assumed it

and can keep it. Thus it is very rare for sovereigns to impose thoroughly

irrational commands, for they are bound to consult their own interests, and

retain their power by consulting the public good and acting according to the

dictates of reason, as Seneca says, "violenta imperia nemo

continuit diu." No one can long retain a tyrant's sway.

In a democracy, irrational commands are still less to be

feared: for it is almost impossible that the majority of a people, especially if

it be a large one, should agree in an irrational design: and, moreover, the

basis and aim of a democracy is to avoid the desires as irrational, and to bring men as far as

possible under the control of reason, so that they may live in peace and harmony: if

this basis be removed the whole fabric falls to ruin.

Such being the ends in view for the sovereign power,

the duty of subjects is, as I have said, to obey its commands, and to recognize

no right save that which it sanctions.

It will, perhaps, be thought that we are turning

subjects into slaves: for slaves obey commands and free men live as they like;

but this idea is based on a misconception, for the true slave is he who is led

away by his pleasures and can neither see what is good for him nor act

accordingly: he alone is free who lives with free consent under the entire

guidance of reason.

Action in obedience to orders does take away freedom in a certain sense, but it does not, therefore, make a man a slave, all depends on the object of the action. If the object of the action be the good of the state, and not the good of the agent, the latter is a slave and does himself no good: but in a state or kingdom where the weal of the whole people, and not that of the ruler, is the supreme law, obedience to the sovereign power does not make a man a slave, of no use to himself, but a subject. Therefore, that state is the freest whose laws are founded on sound reason, so that every member of it may, if he will, be free [N27]; that is, live with full consent under the entire guidance of reason.

Children, though they are bound to obey all the

commands of their parents, are yet not slaves: for the commands of parents look

generally to the children's benefit.

We must, therefore, acknowledge a great difference

between a slave, a son, and a subject; their positions may be thus defined. A

slave is one who is bound to obey his master's orders, though they are given

solely in the master's interest: a son is one who obeys his father's orders,

given in his own interest; a subject obeys the orders of the sovereign power,

given for the common interest, wherein he is included.

I think I have now shown sufficiently clearly the

basis of a democracy: I have especially desired to do so, for I

believe it to be of all forms of government the most natural, and the most consonant

with individual liberty. In it no one transfers his natural right so absolutely that he has no further

voice in affairs, he only hands it over to the majority of a society, whereof he is a unit. Thus all men remain as

they were in the state of nature, equals.

This is the only form of government which I have treated of at length, for it is

the one most akin to my purpose of showing the benefits of freedom in a state.

I may pass over the fundamental principles of other

forms of government, for we may gather from what has been said

whence their right arises without going into its origin. The possessor of

sovereign power, whether he be one, or many, or the whole body politic, has the sovereign right of imposing any

commands he pleases: and he who has either voluntarily, or under compulsion,

transferred the right to defend him to another, has, in so doing, renounced his

natural right and is therefore bound to obey, in all

things, the commands of the sovereign power; and will be bound so to do so long

as the king, or nobles, or the people preserve the sovereign power which formed

the basis of the original transfer. I need add no more.

The bases and rights of dominion being thus displayed,

we shall readily be able to define private civil right, wrong, justice, and

injustice, with their relations to the state; and also to determine what constitutes an ally,

or an enemy, or the crime of treason.

By private civil right we can only mean the liberty

every man possesses to preserve his existence, a liberty limited by the edicts

of the sovereign power, and preserved only by its authority: for when a man has

transferred to another his right of living as he likes, which was only limited by

his power, that is, has transferred his liberty and power of self-defence, he is

bound to live as that other dictates, and to trust to him entirely for his

defence. Wrong takes place when a citizen, or subject, is forced by another to

undergo some loss or pain in contradiction to the authority of the law, or the

edict of the sovereign power.

Wrong is conceivable only in an organized community:

nor can it ever accrue to subjects from any act of the sovereign, who has the

right to do what he likes. It can only arise, therefore, between private

persons, who are bound by law and right not to injure one another. Justice

consists in the habitual rendering to every man his lawful due: injustice

consists in depriving a man, under the pretence of legality, of what the laws,

rightly interpreted, would allow him. These last are also called equity and

iniquity, because those who administer the laws are bound to show no respect of

persons, but to account all men equal, and to defend every man's right equally,

neither envying the rich nor despising the poor.

The men of two states become allies, when for the sake of avoiding

war, or for some other advantage, they covenant to do each other no hurt, but on

the contrary, to assist each other if necessity arises, each retaining his

independence. Such a covenant is valid so long as its basis of danger or

advantage is in force: no one enters into an engagement, or is bound to stand by

his compacts unless there be a hope of some accruing good, or the fear of some

evil: if this basis be removed the compact thereby becomes void: this has been

abundantly shown by experience. For although different states make treaties not

to harm one another, they always take every possible precaution against such

treaties being broken by the stronger party, and do not rely on the compact,

unless there is a sufficiently obvious object and advantage to both parties in

observing it. Otherwise they would fear a breach of faith, nor would there be

any wrong done thereby: for who in his proper senses, and aware of the right of

the sovereign power, would trust in the promises of one who has the will and the

power to do what he likes, and who aims solely at the safety and advantage of

his dominion? Moreover, if we consult loyalty and religion, we shall see that no

one in possession of power ought to abide by his promises to the injury of his

dominion; for he cannot keep such promises without breaking the engagement he

made with his subjects, by which both he and they are most solemnly bound.

An enemy is one who lives apart from the state, and does not recognize its authority either as a

subject or as an ally. It is not hatred which makes a man an enemy, but the

rights of the state. The rights of the state are the same in regard to him who does not

recognize by any compact the state authority, as they are against him who has

done the state an injury: it has the right to force him as best it can, either

to submit, or to contract an alliance.

Lastly, treason can only be committed by subjects, who

by compact, either tacit or expressed, have transferred all their rights to the state: a subject is said to have committed this crime

when he has attempted, for whatever reason, to seize the sovereign power, or to

place it in different hands. I say, has attempted, for if punishment were not to

overtake him till he had succeeded, it would often come too late, the sovereign

rights would have been acquired or transferred already.

I also say, has attempted, for whatever reason, to

seize the sovereign power, and I recognize no difference whether such an attempt

should be followed by public loss or public gain. Whatever be his reason for

acting, the crime is treason, and he is rightly condemned: in war, everyone

would admit the justice of his sentence. If a man does not keep to his post, but

approaches the enemy without the knowledge of his commander, whatever may be his

motive, so long as he acts on his own motion, even if he advances with the

design of defeating the enemy, he is rightly put to death, because he has

violated his oath, and infringed the rights of his commander. That all citizens

are equally bound by these rights in time of peace, is not so generally

recognized, but the reasons for obedience are in both cases identical. The state must be preserved and directed by the sole

authority of the sovereign, and such authority and right have been accorded by

universal consent to him alone: if, therefore, anyone else attempts, without his

consent, to execute any public enterprise, even though the state might (as we said) reap benefit therefrom, such

person has none the less infringed the sovereigns right, and would be rightly

punished for treason.

In order that every scruple may be removed, we may now

answer the inquiry, whether our former assertion that everyone who has not the

practice of reason, may, in the state of nature, live by sovereign

right natural, according to the laws of his desires, is not in direct opposition to the law and

right of God as revealed. For as all men absolutely (whether they be less

endowed with reason or more) are equally bound by the Divine command to love

their neighbour as themselves, it may be said that they cannot, without wrong,

do injury to anyone, or live according to their desires.

This objection, so far as the state of nature is concerned, can be easily answered, for the state of nature is, both in nature and in time, prior to religion. No one knows by nature that he owes any obedience to God [N28], nor can he attain thereto by any exercise of his reason, but solely by revelation confirmed by signs. Therefore, previous to revelation, no one is bound by a Divine law and right of which he is necessarily in ignorance. The state of nature must by no means be confounded with a state of religion, but must be conceived as without either religion or law, and consequently without sin or wrong: this is how we have described it, and we are confirmed by the authority of Paul. It is not only in respect of ignorance that we conceive the state of nature as prior to, and lacking the Divine revealed law and right; but in respect of freedom also, wherewith all men are born endowed.

If men were naturally bound by the Divine law and right, or if the Divine law and right were a natural necessity, there

would have been no need for God to make a covenant with mankind, and to bind

them thereto with an oath and agreement.

We must, then, fully grant that the Divine law and right originated at the time when men by

express covenant agreed to obey God in all things, and ceded, as it were, their

natural freedom, transferring their rights to God in the manner described in speaking of

the formation of a state.

However, I will treat of these matters more at length

presently.

It may be insisted that sovereigns are as much bound

by the Divine law as subjects: whereas we have asserted that

they retain their natural rights, and may do whatever they like.

In order to clear up the whole difficulty, which

arises rather concerning the natural right than the natural state, I maintain that

everyone is bound, in the state of nature, to live according to Divine law, in the same way as he is bound to live

according to the dictates of sound reason; namely, inasmuch as it is to his advantage, and

necessary for his salvation; but, if he will not so live, he may do otherwise at

his own risk. He is thus bound to live according to his own laws, not according

to anyone else's, and to recognize no man as a judge, or as a superior in

religion. Such, in my opinion, is the position of a sovereign, for he may take

advice from his fellow-men, but he is not bound to recognize any as a judge, nor

anyone besides himself as an arbitrator on any question of right, unless it be a

prophet sent expressly by God and attesting his mission by indisputable signs.

Even then he does not recognize a man, but God Himself as His judge.

If a sovereign refuses to obey God as revealed in His

law, he does so at his own risk and loss, but without violating any civil or natural right. For the civil right is dependent on his

own decree; and natural right is dependent on the laws of nature, which

latter are not adapted to religion, whose sole aim is the good of humanity, but

to the order of nature - that is, to God's eternal decree unknown to us.

This truth seems to be adumbrated in a somewhat obscurer form by those who

maintain that men can sin against God's revelation, but not against the eternal decree by which He has ordained all things.

We may be asked, what should we do if the sovereign

commands anything contrary to religion, and the obedience which we have

expressly vowed to God? should we obey the Divine law or the human law? I shall treat of this question at length

hereafter, and will therefore merely say now, that God should be obeyed before

all else, when we have a certain and indisputable revelation of His will: but men are very prone to error

on religious subjects, and, according to the diversity of their dispositions,

are wont with considerable stir to put forward their own inventions, as

experience more than sufficiently attests, so that if no one were bound to obey

the state in matters which, in his own opinion concern

religion, the rights of the state would be dependent on every man's judgment and

passions. No one would consider himself bound to obey laws framed against his

faith or superstition; and on this pretext he might assume

unbounded license. In this way, the rights of the civil authorities would be

utterly set at nought, so that we must conclude that the sovereign power, which

alone is bound both by Divine and natural right to preserve and guard the laws of the state, should have supreme authority for making any

laws about religion which it thinks fit; all are bound to obey its behests on

the subject in accordance with their promise which God bids them to keep.

However, if the sovereign power be heathen, we should either enter into no engagements therewith, and yield up our lives sooner than transfer to it any of our rights; or, if the engagement be made, and our rights transferred, we should (inasmuch as we should have ourselves transferred the right of defending ourselves and our religion) be bound to obey them, and to keep our word: we might even rightly be bound so to do, except in those cases where God, by indisputable revelation, has promised His special aid against tyranny, or given us special exemption from obedience. Thus we see that, of all the Jews in Babylon, there were only three youths who were certain of the help of God, and, therefore, refused to obey Nebuchadnezzar. All the rest, with the sole exception of Daniel, who was beloved by the king, were doubtless compelled by right to obey, perhaps thinking that they had been delivered up by God into the hands of the king, and that the king had obtained and preserved his dominion by God's design. On the other hand, Eleazar, before his country had utterly fallen, wished to give a proof of his constancy to his compatriots, in order that they might follow in his footsteps, and go to any lengths, rather than allow their right and power to be transferred to the Greeks, or brave any torture rather than swear allegiance to the heathen. Instances are occurring every day in confirmation of what I here advance. The rulers of Christian kingdoms do not hesitate, with a view to strengthening their dominion, to make treaties with Turks and heathen, and to give orders to their subjects who settle among such peoples not to assume more freedom, either in things secular or religious, than is set down in the treaty, or allowed by the foreign government. We may see this exemplified in the Dutch treaty with the Japanese, which I have already mentioned.

[Note N26]: "No one can honestly promise to forego the right which he has over all things." In the state of social life, where general right determines what is

good or evil, stratagem is rightly distinguished as of two kinds, good and evil.

But in the state of Nature, where every man is his own judge, possessing the

absolute right to lay down laws for himself, to interpret them

as he pleases, or to abrogate them if he thinks it convenient, it is not

conceivable that stratagem should be evil.

[Note N27]: "Every member of it may, if he will, be free." Whatever be

the social state a man finds himself in, he may be free. For

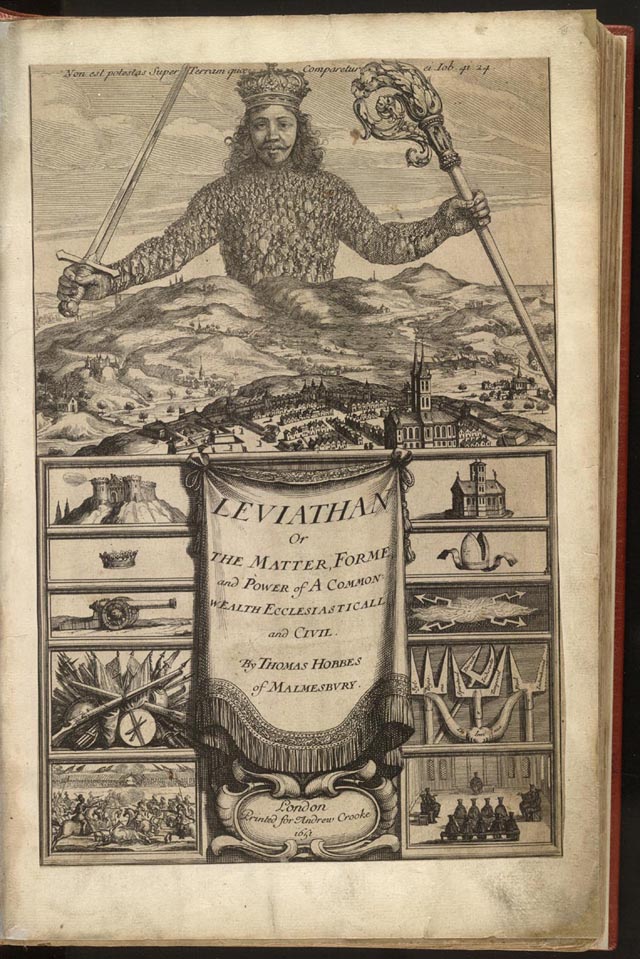

certainly a man is free, in so far as he is led by reason. Now reason (though Hobbes thinks otherwise) is

always on the side of peace, which cannot be attained unless the general laws of

the state be respected. Therefore the more he is free, the

more constantly will he respect the laws of his country, and obey the commands

of the sovereign power to which he is subject.

[Note N28]: "No one knows by nature that he owes any obedience to God." When Paul says that men have in themselves no refuge, he speaks as a man: for in the ninth chapter of the same epistle he expressly teaches that God has mercy on whom He will, and that men are without excuse, only because they are in God's power like clay in the hands of a potter, who out of the same lump makes vessels, some for honour and some for dishonour, not because they have been forewarned. As regards the Divine natural law whereof the chief commandment is, as we have said, to love God, I have called it a law in the same sense, as philosophers style laws those general rules of nature, according to which everything happens. For the love of God is not a state of obedience: it is a virtue which necessarily exists in a man who knows God rightly. Obedience has regard to the will of a ruler, not to necessity and truth. Now as we are ignorant of the nature of God's will, and on the other hand know that everything happens solely by God's power, we cannot, except through revelation, know whether God wishes in any way to be honoured as a sovereign. Again; we have shown that the Divine rights appear to us in the light of rights or commands, only so long as we are ignorant of their cause: as soon as their cause is known, they cease to be rights, and we embrace them no longer as rights but as eternal truths; in other words, obedience passes into love of God, which emanates from true knowledge as necessarily as light emanates from the sun. Reason then leads us to love God, but cannot lead us to obey Him; for we cannot embrace the commands of God as Divine, while we are in ignorance of their cause, neither can we rationally conceive God as a sovereign laying down laws as a sovereign.