Chapter 12

Of the True Original of the Divine Law, and Wherefore Scripture Is Called Sacred, and the Word of God. How That, in so far as It Contains the Word of God, It Has Come Down to Us Uncorrupted

Those who look upon the Bible as a message sent down by God from Heaven

to men, will doubtless cry out that I have committed the sin against the Holy

Ghost because I have asserted that the Word of God is faulty, mutilated,

tampered with, and inconsistent; that we possess it only in fragments, and that

the original of the covenant which God made with the Jews has been lost.

However, I have no doubt that a little reflection will cause them to desist from

their uproar: for not only reason but the expressed opinions of prophets and

apostles openly proclaim that God's eternal Word and covenant, no less than true religion, is Divinely inscribed in human hearts,

that is, in the human mind, and that this is the true original of God's

covenant, stamped with His own seal, namely, the idea of Himself, as it were,

with the image of His Godhood.

Religion was imparted to the early Hebrews as a law

written down, because they were at that time in the condition of children, but

afterwards Moses (Deut. xxx:6) and Jeremiah (xxxi:33) predicted a

time coming when the Lord should write His law in their hearts. Thus only the

Jews, and amongst them chiefly the Sadducees, struggled for the law written on

tablets; least of all need those who bear it inscribed on their hearts join in

the contest. Those, therefore, who reflect, will find nothing in what I have

written repugnant either to the Word of God or to true religion and faith, or calculated to weaken either

one or the other: contrariwise, they will see that I have strengthened religion,

as I showed at the end of Chapter 10.; indeed, had it not been so, I should

certainly have decided to hold my peace, nay, I would even have asserted as a

way out of all difficulties that the Bible contains the most profound hidden

mysteries; however, as this doctrine has given rise to gross superstition and other pernicious results spoken of at

the beginning of Chapter 5., I have thought such a course unnecessary,

especially as religion stands in no need of superstitious adornments, but is, on the contrary,

deprived by such trappings of some of her splendour.

Still, it will be said, though the law of God is

written in the heart, the Bible is none the less the Word of God, and it is no

more lawful to say of Scripture than of God's Word that it is mutilated and

corrupted. I fear that such objectors are too anxious to be pious, and that they

are in danger of turning religion into superstition, and worshipping paper and ink in place of

God's Word.

I am certified of thus much: I have said nothing

unworthy of Scripture or God's Word, and I have made no assertions which I could

not prove by most plain argument to be true. I can, therefore, rest assured that

I have advanced nothing which is impious or even savours of impiety.

I confess that some profane men, to whom religion is a

burden, may, from what I have said, assume a licence to sin, and without any

reason, at the simple dictates of their lusts conclude that Scripture is

everywhere faulty and falsified, and that therefore its authority is null; but

such men are beyond the reach of help, for nothing, as the proverb has it, can

be said so rightly that it cannot be twisted into wrong. Those who wish to give

rein to their lusts are at no loss for an excuse, nor were those men of old who

possessed the original Scriptures, the ark of the covenant, nay, the prophets

and apostles in person among them, any better than the people of to-day. Human

nature, Jew as well as Gentile, has always been the same, and in every age

virtue has been exceedingly rare.

Nevertheless, to remove every scruple, I will here

show in what sense the Bible or any inanimate thing should be called sacred and

Divine; also wherein the law of God consists, and how it cannot be contained in

a certain number of books; and, lastly, I will show that Scripture, in so far as

it teaches what is necessary for obedience and salvation, cannot have been

corrupted. From these considerations everyone will be able to judge that I have

neither said anything against the Word of God nor given any foothold to impiety.

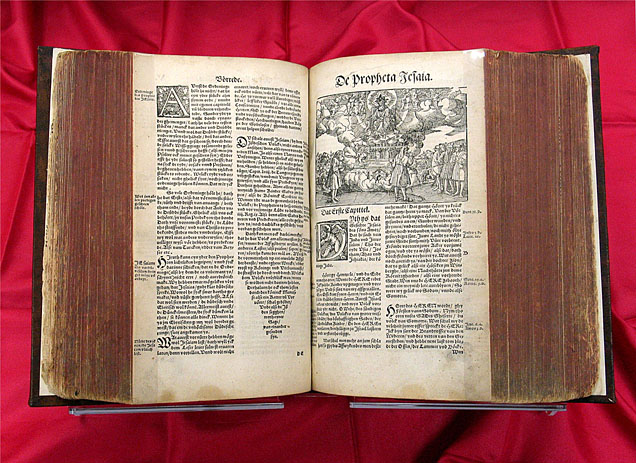

A thing is called sacred and Divine when it is

designed for promoting piety, and continues sacred so long as it is religiously

used: if the users cease to be pious, the thing ceases to be sacred: if it be

turned to base uses, that which was formerly sacred becomes unclean and profane.

For instance, a certain spot was named by the patriarch Jacob the house of God,

because he worshipped God there revealed to him: by the prophets the same spot

was called the house of iniquity (see Amos v:5, and Hosea x:5), because the

Israelites were wont, at the instigation of Jeroboam, to sacrifice there to

idols. Another example puts the matter in the plainest light. Words gain their meaning solely from their usage, and

if they are arranged according to their accepted signification so as to move

those who read them to devotion, they will become sacred, and the book so

written will be sacred also. But if their usage afterwards dies out so that the

words have no meaning, or the book becomes utterly

neglected, whether from unworthy motives, or because it is no longer needed,

then the words and the book will lose both their use and their

sanctity: lastly, if these same words be otherwise arranged, or if their

customary meaning becomes perverted into its opposite, then both the words and the book containing them become, instead of

sacred, impure and profane.

From this it follows

that nothing is in itself absolutely sacred, or profane, and unclean, apart from

the mind, but only relatively thereto. Thus much is clear from many passages in

the Bible. Jeremiah (to select one case out of many) says (chap. vii:4), that

the Jews of his time were wrong in calling Solomon's Temple, the Temple of God,

for, as he goes on to say in the same chapter, God's name would only be given to

the Temple so long as it was frequented by men who worshipped Him, and defended

justice, but that, if it became the resort of murderers, thieves, idolaters, and

other wicked persons, it would be turned into a den of malefactors.

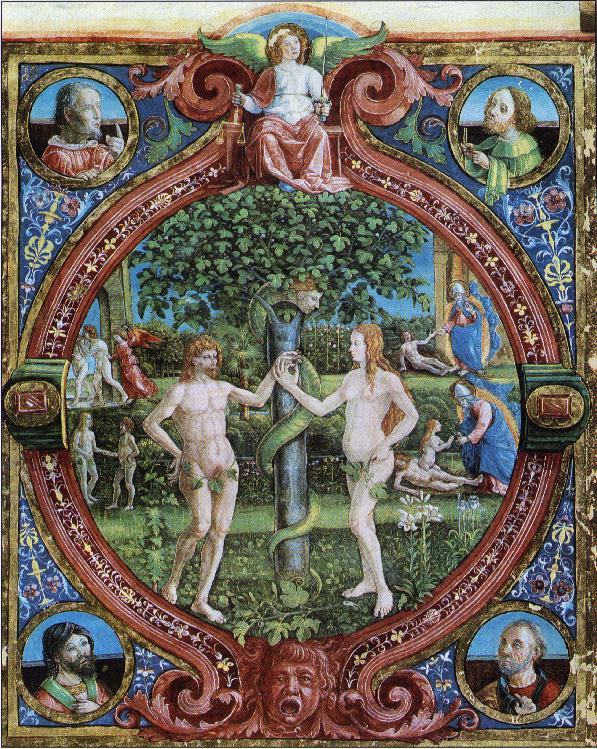

Scripture, curiously enough, nowhere tells us what

became of the Ark of the Covenant, though there is no doubt that it was

destroyed, or burnt together with the Temple; yet there was nothing which the

Hebrews considered more sacred, or held in greater reverence. Thus Scripture is

sacred, and its words Divine so long as it stirs mankind to devotion towards

God: but if it be utterly neglected, as it formerly was by the Jews, it becomes

nothing but paper and ink, and is left to be desecrated or corrupted: still,

though Scripture be thus corrupted or destroyed, we must not say that the Word

of God has suffered in like manner, else we shall be like the Jews, who said

that the Temple which would then be the Temple of God had perished in the

flames. Jeremiah tells us this in respect to the law, for he thus chides the

ungodly of his time, "Wherefore, say you we are masters, and the law of the Lord

is with us? Surely it has been given in vain, it is in vain that the pen of the

scribes " (has been made) - that is, you say falsely that the Scripture is in

your power, and that you possess the law of God; for ye have made it of none

effect.

So also, when Moses broke the first tables of the law, he did not by

any means cast the Word of God from his hands in anger and shatter it - such an

action would be inconceivable, either of Moses or of God's Word - he only broke the tables of

stone, which, though they had before been holy from containing the covenant

wherewith the Jews had bound themselves in obedience to God, had entirely lost

their sanctity when the covenant had been violated by the worship of the calf,

and were, therefore, as liable to perish as the ark of the covenant. It is thus

scarcely to be wondered at, that the original documents of Moses are no longer extant, nor that the books we

possess met with the fate we have described, when we consider that the true

original of the Divine covenant, the most sacred object of all, has totally

perished.

Let them cease, therefore, who accuse us of impiety,

inasmuch as we have said nothing against the Word of God, neither have we

corrupted it, but let them keep their anger, if they would wreak it justly, for

the ancients whose malice desecrated the Ark, the Temple, and the Law of God,

and all that was held sacred, subjecting them to corruption. Furthermore, if,

according to the saying of the Apostle in 2 Cor. iii:3, they possessed "the

Epistle of Christ, written not with ink, but with the Spirit of

the living God, not in tables of stone, but in the fleshy tables of the heart,"

let them cease to worship the letter, and be so anxious concerning it.

I think I have now sufficiently shown in what respect

Scripture should be accounted sacred and Divine; we may now see what should

rightly be understood by the expression, the Word of the Lord; debar (the Hebrew

original) signifies word, speech, command, and thing. The causes for which a

thing is in Hebrew said to be of God, or is referred to Him, have been already

detailed in Chap. 1., and we can therefrom easily gather what meaning Scripture

attaches to the phrases, the word, the speech, the command, or the thing of God.

I need not, therefore, repeat what I there said, nor what was shown under the

third head in the chapter on miracles. It is enough to mention the repetition for

the better understanding of what I am about to say - viz., that the Word of the

Lord when it has reference to anyone but God Himself, signifies that Divine law treated of in Chap. 4.; in other words,

religion, universal and catholic to the whole human race, as Isaiah describes it

(chap. i:10), teaching that the true way of life consists, not in ceremonies,

but in charity, and a true heart, and calling it indifferently God's Law and

God's Word.

The expression is also used metaphorically for the

order of nature and destiny (which, indeed, actually depend and follow from the

eternal mandate of the Divine nature), and especially

for such parts of such order as were foreseen by the prophets, for the prophets

did not perceive future events as the result of natural causes, but as the fiats

and decrees of God. Lastly, it is employed for the command of any prophet, in so

far as he had perceived it by his peculiar faculty or prophetic gift, and not by

the natural light of reason; this use springs chiefly from the usual

prophetic conception of God as a legislator, which we remarked in Chap. 4. There

are, then, three causes for the Bible's being called the Word of God: because it

teaches true religion, of which God is the eternal Founder; because it narrates predictions of

future events as though they were decrees of God; because its actual authors

generally perceived things not by their ordinary natural faculties, but by a

power peculiar to themselves, and introduced these things perceived, as told

them by God.

Although Scripture contains much that is merely historical and can be perceived by natural reason, yet its name is acquired from its chief subject matter.

We can thus easily see how God can be said to be the

Author of the Bible: it is because of the true religion therein contained, and

not because He wished to communicate to men a certain number of books. We can

also learn from hence the reason for the division into Old and New Testament. It

was made because the prophets who preached religion before Christ, preached it as a national law in virtue of the

covenant entered into under Moses; while the Apostles who came after Christ, preached it to all men as a universal religion

solely in virtue of Christ's Passion: the cause for the division is not that the

two parts are different in doctrine, nor that they were written as originals of

the covenant, nor, lastly, that the catholic religion (which is in entire

harmony with our nature) was new except in relation to those who had not known

it: " it was in the world," as John the Evangelist says, " and the world knew it

not."

Thus, even if we had fewer books of the Old and New

Testament than we have, we should still not be deprived of the Word of God

(which, as we have said, is identical with true religion), even as we do not now

hold ourselves to be deprived of it, though we lack many cardinal writings such

as the Book of the Law, which was religiously guarded in the Temple as the

original of the Covenant, also the Book of Wars, the Book of Chronicles, and

many others, from whence the extant Old Testament was taken and compiled. The

above conclusion may be supported by many reasons.

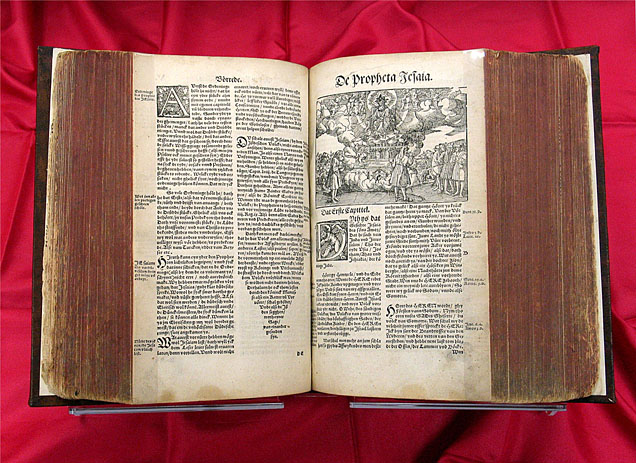

I. Because the books of both Testaments were not

written by express command at one place for all ages, but are a fortuitous

collection of the works of men, writing each as his period and disposition

dictated. So much is clearly shown by the call of the prophets who were bade to

admonish the ungodly of their time, and also by the Apostolic Epistles.

II. Because it is one thing to understand the meaning

of Scripture and the prophets, and quite another thing to understand the meaning

of God, or the actual truth. This follows from what we said in Chap. 2. We

showed, in Chap. 6., that it applied to historic narratives, and to miracles: but it by no means applies to questions

concerning true religion and virtue.

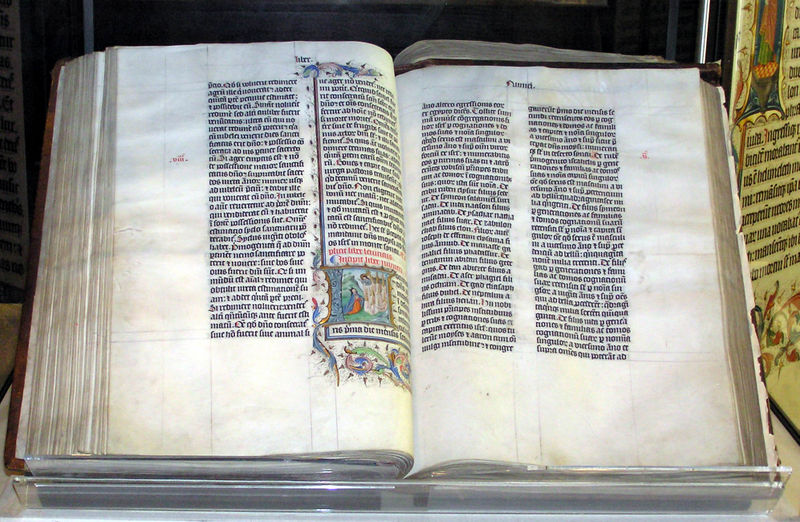

III. Because the books of the Old Testament were

selected from many, and were collected and sanctioned by a council of the

Pharisees, as we showed in Chap. 10. The books of the New Testament were also

chosen from many by councils which rejected as spurious other books held sacred

by many. But these councils, both Pharisee and Christian, were not composed of

prophets, but only of learned men and teachers. Still, we must grant that they

were guided in their choice by a regard for the Word of God ; and they must,

therefore, have known what the law of God was.

IV. Because the Apostles wrote not as prophets, but as

teachers (see last Chapter), and chose whatever method they thought best adapted

for those whom they addressed: and consequently, there are many things in the

Epistles (as we showed at the end of the last Chapter) which are not necessary

to salvation.

V. Lastly, because there are four Evangelists in the

New Testament, and it is scarcely credible that God can have designed to narrate

the life of Christ four times over, and to communicate it thus to

mankind. For though there are some details related in one Gospel which are not

in another, and one often helps us to understand another, we cannot thence

conclude that all that is set down is of vital importance to us, and that God

chose the four Evangelists in order that the life of Christ might be better understood; for each one

preached his Gospel in a separate locality, each wrote it down as he preached

it, in simple language, in order that the history of Christ might be clearly told, not with any view of

explaining his fellow-Evangelists.

If there are some passages which can be better, and more easily understood by comparing the various versions, they are the result of chance, and are not numerous: their continuance in obscurity would have impaired neither the clearness of the narrative nor the blessedness of mankind.

We have now shown that Scripture can only be called

the Word of God in so far as it affects religion, or the Divine law; we must now point out that, in respect to

these questions, it is neither faulty, tampered with, nor corrupt. By faulty,

tampered with, and corrupt, I here mean written so incorrectly, that the meaning

cannot be arrived at by a study of the language, nor from the authority of

Scripture. I will not go to such lengths as to say that the Bible, in so far as

it contains the Divine law, has always preserved the same vowel-points,

the same letters, or the same words (I leave this to be proved by, the

Massoretes and other worshippers of the letter), I only, maintain that the

meaning by, which alone an utterance is entitled to be called Divine, has come

down to us uncorrupted, even though the original wording may have been more

often changed than we suppose. Such alterations, as I have said above, detract

nothing from the Divinity of the Bible, for the Bible would have been no less

Divine had it been written in different words or a different language. That the

Divine law has in this sense come down to us

uncorrupted, is an assertion which admits of no dispute. For from the Bible

itself we learn, without the smallest difficulty or ambiguity,, that its

cardinal precept is: To love God above all things, and one's neighbour as one's

self. This cannot be a spurious passage, nor due to a hasty and mistaken scribe,

for if the Bible had ever put forth a different doctrine it would have had to

change the whole of its teaching, for this is the corner-stone of religion,

without which the whole fabric would fall headlong to the ground. The Bible

would not be the work we have been examining, but something quite different.

We remain, then, unshaken in our belief that this has

always been the doctrine of Scripture, and, consequently, that no error

sufficient to vitiate it can have crept in without being instantly, observed by

all; nor can anyone have succeeded in tampering with it and escaped the

discovery of his malice.

As this corner-stone is intact, we must perforce admit

the same of whatever other passages are indisputably dependent on it, and are

also fundamental, as, for instance, that a God exists, that He foresees all

things, that He is Almighty, that by His decree the good prosper and the wicked

come to naught, and, finally, that our salvation depends solely on His grace.

These are doctrines which Scripture plainly teaches

throughout, and which it is bound to teach, else all the rest would be empty and

baseless; nor can we be less positive about other moral doctrines, which plainly

are built upon this universal foundation - for instance, to uphold justice, to

aid the weak, to do no murder, to covet no man's goods, &c. Precepts, I

repeat, such as these, human malice and the lapse of ages are alike powerless to

destroy, for if any part of them perished, its loss would immediately be

supplied from the fundamental principle, especially the doctrine of charity,

which is everywhere in both Testaments extolled above all others. Moreover,

though it be true that there is no conceivable crime so heinous that it has

never been committed, still there is no one who would attempt in excuse for his

crimes to destroy, the law, or introduce an impious doctrine in the place of

what is eternal and salutary; men's nature is so constituted that everyone (be

he king or subject) who has committed a base action, tries to deck out his

conduct with spurious excuses, till he seems to have done nothing but what is

just and right.

We may conclude, therefore, that the whole Divine law, as taught by Scripture, has come down to us uncorrupted. Besides this there are certain facts which we may be sure have been transmitted in good faith. For instance, the main facts of Hebrew history, which were perfectly well known to everyone. The Jewish people were accustomed in former times to chant the ancient history of their nation in psalms. The main facts, also, of Christ's life and passion were immediately spread abroad through the whole Roman empire. It is therefore scarcely credible, unless nearly everybody, consented thereto, which we cannot suppose, that successive generations have handed down the broad outline of the Gospel narrative otherwise than as they received it.

Whatsoever, therefore, is spurious or faulty can only have reference to details - some circumstances in one or the other history or prophecy designed to stir the people to greater devotion; or in some miracle, with a view of confounding philosophers; or, lastly, in speculative matters after they had become mixed up with religion, so that some individual might prop up his own inventions with a pretext of Divine authority. But such matters have little to do with salvation, whether they be corrupted little or much, as I will show in detail in the next chapter, though I think the question sufficiently plain from what I have said already, especially in Chapter 2.