| September 20, 2004 | |||||||||||

|

A Torture Killing by U.S. Forces in Afghanistan

By Craig Pyes |

|||||||||||

|

On March 1, 2003, U.S. Special Forces arrested eight Afghan soldiers at a checkpoint on a remote mountain pass in South-Eastern Afghanistan. The men were members of the Afghan army, supposedly allies of the United States in the fight against al-Qaeda and the remnants of the Taliban forces. Nevertheless they were taken for interrogation at a U.S. firebase near the town of Gardez. Seventeen days later, seven of the men were transferred to custody of the local Afghan police. Many were suffering from serious injuries - the result of what they later described as torture at the hands of American interrogators. The other detainee was dead. An unreleased report based on an investigation by Afghan military investigators concluded that he had most likely died as a result of his treatment by U.S. forces, and that there was a "strong possibility" that his death qualified as murder. The incident at Gardez - which appears to be one of the worst instances of torture and prisoner abuse carried out by U.S. forces in Afghanistan - has never before been publicly reported. It was uncovered by a special investigation carried out on behalf of the Crimes of War Project, in conjunction with the Human Rights Center at the University of California, Berkeley. This account is based on the unpublished report by Afghan military investigators, a separate memorandum by officials of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA), several other official Afghan documents, and interviews with a number of people with direct knowledge of the story. Together, these provide evidence not only of appalling mistreatment of detainees - in direct violation of U.S. and international law - but also of an attempt to put pressure on local Afghan officials to cover up what had taken place.

Gardez is the capital of Paktia province - a region near Afghanistan's border with Pakistan. In early 2003 it was the site of active U.S. military operations, since commanders believed that many al-Qaeda and Taliban fugitives had taken refuge there. At the same time there was a complex and intense power struggle going on between a local warlord, Pacha Khan Zadran, the appointed provincial governor, Raz Mohammad Dalili, and local Afghan military and police commanders. One focus of the struggle was control of the main road between Gardez and Khost, which formed part of an important trade route with Pakistan. Both local military forces and fighters loyal to Pacha Khan Zadran had been accused of extracting bribes from passing vehicles.

"Major Mike" in Action According to international security officials, the Special Forces leader known as "Mike" was particularly concerned that local military and police commanders might have continued links with al-Qaeda or Taliban fighters and might be selling them weapons. At a UNAMA-sponsored security meeting in early March, Mike stood up and warned the commanders that he would kill them if they released "Taliban" prisoners or sided with "those opposing the Coalition," according to a report mentioning the incident. An official who was present at the meeting told me that Mike explicitly warned the Gardez police chief, Abdullah Mujahid, about "conniving" with anti-government elements that were planting mines against his men. "I know what you're doing," the official recalled Mike saying. "You will not live to spend that money, because I will kill you." On March 1, a group of U.S. Special Forces drew up to a checkpoint manned by eight members of the 3rd Corps of the Afghan army at the Sato Kandaw pass on the Gardez-Khost road. According to testimony later given by the Afghan soldiers to military prosecutors, the Americans said they would join the Afghans for tea, then pulled out their weapons. The Afghan fighters were handcuffed, shackled and blindfolded. Several told prosecutors that they were hit with rifle butts. "The behavior of the authorities was completely wild," according to the account of one soldier named Momin. He said they were taken to the American compound "like animals." The detention center at the Gardez base was what is known as a "forward collection point" - that is, a transit site where military detainees can be held while their transfer to a more permanent holding facility is arranged. The United States armed forces maintained two official long-term detention centers in Afghanistan - at Bagram Air Base, outside Kabul, and in the southern city of Kandahar. The report by the U.S. Army Inspector General on detainee operations published on July 21, 2004, says that by doctrine forward collection points "can hold detainees for up to 12 hours before evacuating to division central CPs [collection points]," though it adds that doctrine "does not address the unique characteristics" of Operation Enduring Freedom. The Afghan soldiers detained at Sato Kandaw were held and interrogated at Gardez for 17 days, according to the official Afghan report.

Systematic and Grave Abuse The 25-year-old commander of the group of soldiers, Pare, told prosecutors, "It felt like they were hitting us with a cable or something made of rubber." (All detainees were hooded or blindfolded during interrogation.) "This beating went on for seventeen or eighteen days." In another interview he said he was "seriously beaten by karate, cables, and sticks, and subjected to electric shocks." Gul Karim, another of those arrested, told prosecutors, "I was taken to the compound and they immersed me in cold water...while we were in the compound we were beaten a lot." A third detainee, Momin, said, "I was beaten very hard with punches and kicks. I was seriously injured from the beatings."

"They poured water on us and threw us in the snow and beat us up," recounted another of the soldiers, Noor Mohammad. "They were throwing us against the wall. We were beaten with sticks." According to the statement of a fifth, Hazarat Wali, "They poured water on us. They were continuously beating us. And our hands and feet were shackled."

According to one of the military prosecutors whom I interviewed, some of the detainees told him that they had been suspended upside down while they were being beaten.

Some of the detainees told the investigators that two of Pare's toenails had been torn out, but he himself never made this claim. Although two of his toenails were missing in a later medical examination, it is possible they fell out because of the blows to his toes, rather than being pulled out as part of his torture.

At no point during their stay at the Gardez base, the men later told representatives of UNAMA, did the Americans offer them any medical treatment for the injuries they received.

All this time, according to the detainees' statements, they were being questioned about links with anti-government forces. Some reported that they were also interrogated about whether they had held up cars on the Gardez-Khost road. Governor Dalili said in an interview for this investigation that he believed Pare and his men had been collecting money from travelers and harassing women, and that he had reported this to the Special Forces commander known as "Mike." "We reported to Mike, and Mike arrested them," he told me.

A Death in U.S. Custody

Jamal said he wanted to go to the toilet. Two Afghans took him under the arms and helped him outside behind a building in back. They passed a long tent where the detainees were being housed ready for transfer to the city jail. Commander Pare was sitting outside the tent in the sunshine and watched them pass. It was the last time he would see his brother alive.

Outside of Pare's view, Jamal started to loosen his trousers. Then his body went limp, and he started to collapse. The two Afghans helped him to sit on the ground. A moment later his eyes rolled upward in a frozen stare. The Afghans informed the compound doctors, and Jamal's body was carried to the tent by American medics.

A few hours later, around 5 o'clock in the afternoon, Pare was allowed into the tent to see his brother's body. "When I entered I saw a plastic tube in my brother's mouth and an intravenous needle in his arm," Pare later told investigators. "And as I was looking at him, three of the high-ranking foreigners came and told the translators to ask me who had beaten the person up. And I told them, 'I was blindfolded. And I couldn't see because he was separated from me.' At the same time, one of the foreigners grabbed the collar of another of the foreigners and told him that this person should not have been tortured, but just shot." The Afghan who had been with Jamal when he died came into the tent shortly afterward, he told me. The two men prepared the corpse in the Muslim mourning tradition, tying a white scarf under the chin and over the head to keep the mouth closed. They then turned the dead man so that he would be facing Mecca. Shortly afterwards, according to the account Pare gave the Afghan military investigators, "One of the high-ranking foreigners returned and said: 'We respect your religion. Please forgive us. We acted very badly towards you because of a misunderstanding.' And they asked whether there was anything they could do to make amends. And I told them I would never desecrate my brother's martyrdom, and even if they gave me something I would burn it."

"Because of the beatings by the American forces," Pare told investigators, "my brother Jamal was martyred, and I was almost beaten to death myself. But in the end they weren't able to show that we had any kind of ties or relationship with al-Qaeda."

Disposing of the Body According to my own interviews and official records, none of the doctors at the hospital performed an autopsy. When I talked to the deputy administrator of the hospital, she said that none of the doctors wanted to look into the cause of death because they were afraid that they would be beaten again by the police. Finally that night, the administrator persuaded the guard at the Maternity Hospital, Haji Abdul Qayum, an elderly man with an untrimmed grey beard, to wash and prepare the body for burial. In an interview, Qayum said that the first thing he did after taking charge of the body was to tear off the filthy clothes and throw them away. As he did so, he said, a cable fell out of the trouser leg of the dead man's shalwar kameez. Qayum described this as an insulated wire roughly a foot long and about the thickness of a finger, with two small copper loops at each end.

Asked about the condition of the body, he said, "The skin was not broken. I couldn't see any cuts or blood, except for a little dried blood in the ears. There was swelling, especially on the knees, the shins, the arms. His face was completely swollen, as were his palms, and the soles of his feet were swollen double in size. The face was dark and looked like it was burnt, and both eyes were swollen shut. His back was also swollen, but I don't remember any bruises. But the worst injuries went from the soles of the feet, shins and just over the kneecaps. I did not see any bruises on the genitals." After being put in a coffin, Qayum said, the body was sent back to his family for burial. It was received by the brother's mother, Kajala. In a statement given to the Afghan military investigation, she said, "I saw the body myself. The chest was injured. The legs were injured. The entire body was full of injuries." The prosecutor who took her statement told me that she was crying too much to give any more information.

Keeping the Evidence Out of Sight The remaining seven detainees were then transferred to the custody of the local Afghan police in Gardez. According to the later Afghan military investigation, this was arranged after the Americans contacted the governor of Paktia and other security authorities. At this point, no Afghan civil or military agency had any reason to believe that the men had committed a crime or were linked to anti-government fighters. Nevertheless, the Attorney General's investigation noted, the seven soldiers were kept for a month and a half at the Gardez police facility with as many as 13 other inmates in a "secret detention room" built for 5 people. The sole reason for their continued detention, the investigators believed, was because the Americans wanted the prisoners hidden until their wounds had time to heal.

Eye-witness accounts of the detainees' arrival at the police fortress depict them in a bedraggled state, still dressed in the same filthy clothes they had been arrested in over two weeks before, with serious injuries and wounds seeping and unbandaged. The men's condition was also confirmed by the chief of police, who told the military prosecutors that the detainees transferred by the Americans had arrived with injuries that looked like they had been caused by blows, and that the health department of the police had contacted the local hospital to arrange medical treatment. Dr. Ulrahman, the civilian doctor who had helped bring back Jamal's body from the firebase, told me that he examined Commander Pare. "His feet were completely black," said the doctor. "It was caused by blunt force trauma. There was hematoma, bruises, and abrasions. Pare told me that he had been beaten by the Americans at the compound." Less than a week later, a delegation from UNAMA interviewed the men at the detention center, and described the injuries similarly. Of the seven soldiers they interviewed, a UNAMA report said that two of the men were visibly wounded, and one of them was unable to walk as a result of beatings to his knees and legs. Pare's legs were bandaged and his big toe was black and burned, the report said. Pare and his men stressed to the UNAMA representatives in private that the injuries had been inflicted by U.S. forces, and not by their Afghan trainees or the Gardez police.

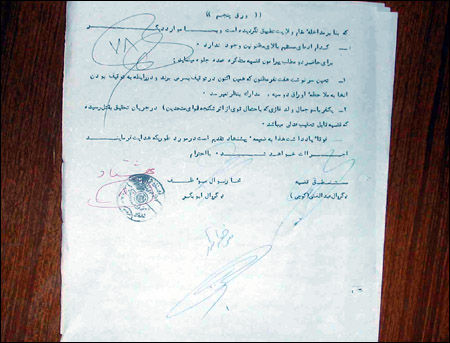

On March 23, Abdullah Mujahid, the police chief, wrote to Governor Dalili, stating that the seven people arrested by the Americans had been transferred to his custody based upon the governor's personal order. But, he continued, he had as yet received any arrest warrants or formal charges, and he was at a loss about how to proceed with the case. Around the same time, Mujahid told representatives of UNAMA that he was only keeping the men in detention because the Coalition had requested it. The official file on the case, held by Afghan military prosecutors and reviewed during the course of this investigation, is filled with communications between Afghan civilian and military authorities trying to find out whether there was any reason that the men should still be detained. When no state agency could come up with any evidence of wrongdoing, military officials conjectured that the "foreign friends" might have independent intelligence from their war on terror as to why the men had been arrested. Perhaps they committed a "political crime," one military official wrote. On April 5, a group of tribal elders of the Totakhail tribe to which Pare and a number of those detained belonged, petitioned the governor asking that either the soldiers be charged in a court of law or released from custody. A week later, an investigative commission appointed by Governor Dalili reported after contacting all local civilian and military law enforcement and intelligence agencies, that it had been unable to discover the reason for the seven mens' arrest or detention, and that the Coalition had not provided any information justifying its actions. "Even though they were badly tortured by Coalition interrogators, none of the detainees confessed to any guilt," noted the military investigators' summary of the commission's findings.

The Afghan Army Takes Up the Case

Within days, the Attorney General of the Armed Forces had dispatched a military prosecutor, Colonel Abdulghani Kochai, to the Kabul prison to interview the detainees. What he saw was shocking, he reported. The men still showed signs of serious torture. Some could not even sit down because of the beatings they'd received, Pare was missing 2 toenails of his left foot, and some showed markings that they said came from electric shocks. A prison doctor's report dated May 7, 2003 confirms much of Mr. Kochai's account. It says that all the prisoners exhibited signs of post traumatic stress disorder from the torture, and that signs of the beatings were still visible on their bodies, evidence that they had been "struck very hard." On the basis of these findings, prosecutors were sent to Gardez to conduct a full investigation. Their report emphasized two main findings. Firstly, there was no evidence of any guilt against the prisoners who had been arrested by the coalition forces. Secondly, they wrote, there was a "strong probability that one of them, Jamal, son of Ghazi, has been murdered as a result of torture by the allied forces during his interrogation." They recommended that Jamal's case be considered for criminal prosecution. "This matter can be pursued legally," they wrote.

The prosecutors' report was presented on May 30, 2003 to Afghanistan's Attorney General, Mahmood Daqiq. Acting on the first finding, he immediately ordered that the men be released. According to the military prosecutors, the second finding received no reply. Nevertheless the prosecutors filed the case away using a law that has a 10-year statute of limitation. "This is a very good case," Haji Qayum, the current Attorney General for the Armed Forces, told me in an interview. "But the Americans won't accept our legal system. They say we are not allowed to investigate U.S. actions in Afghanistan." NOTE: At the final stage of this investigation, the Crimes of War Project shared its findings with the Los Angeles Times. As a result of the newspaper's enquiries, the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Division confirmed on Monday September 20 that it is opening a criminal investigation into the death of Jamal and the treatment of the other detainees.Pentagon authorities also confirmed that there was no record of the case having been reported through channels, although Army regulations require that every death in custody be investigated. UPDATE: The story uncovered through this investigation was mentioned in a statement by Sen. Patrick Leahy (D.-Vermont), the ranking Democrat member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, on October 1, 2004, and raised in a letter that Sen. Leahy sent to Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld on the same day. Sen. Leahy's statement is available on his website. Sen. Leahy's letter was read into the Congressional Record on October 9, 2004, and is available here (in .pdf format).

Craig Pyes is a freelance investigative journalist who has worked with the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, and NBC News. He has been awarded two Pulitzer prizes as well as the Hal Boyle Award from the Overseas Press Club. He was commissioned by the Crimes of War Project to conduct this special investigation. Dr. Farouq Samim provided assistance in Afghanistan.

|

|||||||||||

This site © Crimes of War Project 1999-2004 |

|